We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

The 4 Core Values of First-Generation Wealthy Donors You Need to Understand

Wealth is becoming more concentrated among fewer people.

You probably know that already. But what you may not understand is that first-generation wealthy people are very different from people who are born into wealth. And even more startling, they make up the majority of people defined as wealthy.

Newly wealthy families view the world and their finances very differently than people who grew up having plenty of everything.

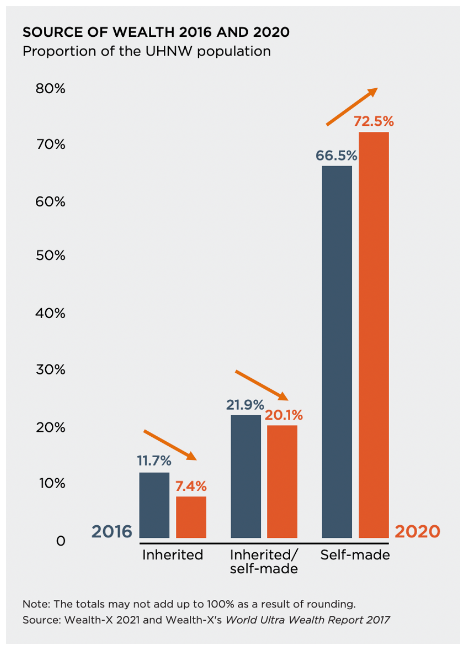

This is not a small segment. 72.5% of wealthy people earned their wealth themselves, while only 7.4% inherited all of it and never had to work. The rest earned some and inherited some.

Yet, when we look at popular media and even our own biases, is that how we view the wealthy? Did you realize that more than two-thirds of wealthy people made their money on their own?

A book on the subject (titled, The Rich In Public Opinion — What We Think When We Think About Wealth and written by Rainer Zitelmann) studied ‘social envy’ by analyzing the framing of the rich in Hollywood films. Although the research found that wealthy characters are depicted as intelligent and competent, that’s where the positivity ends. They are predominantly portrayed in a negative light.

Hollywood makes them out to be profit-hungry people who are only interested in money, prepared to act ruthlessly without moral scruples, and they’ll essentially do whatever it takes (including climbing over dead bodies) to get what they want. In other words the rich are generally made out to be morally reprehensible, cold, callous, and ruthless people.

However, how they are portrayed is inaccurate at best and down right prejudiced at worst. It would be suffice to say that nonprofits, and particularly administrators, would benefit from doing a better job of understanding, and relating to this demographic.

Why?

As a new report from Leadership Story Lab reveals, about $15 trillion stands to be passed down over the next ten years from wealthy families (defined as having $5 million or more in assets). And of that amount, $3 trillion is expected to be donated to charitable organizations.

A large percentage of that will be coming from first-generation wealthy families.

As the report makes clear, not only do these people look at wealth and charitable giving differently than established wealthy families, but they have also been almost completely overlooked or misidentified by wealth screeners and prospect researchers.

The study involved interviews with 20 first-generation wealth (FGW) creators and families living in the United States. According to the author, the majority of the interviewees created their wealth through entrepreneurship, while a few led lucrative corporate careers. All of the study participants held at least $5 million in assets. The median net worth in the group ranged from $50 million to $80 million in assets. Their ages ranged from 49 to 85 years old.

Interestingly, not one could recall having a conversation with a gift officer from a nonprofit. That means a lot of money that could be donated is slipping through the cracks in your process.

To fix that problem, you need to do two things.

First, you must learn how to engage, cultivate, qualify and prioritize these people among the many others in your database. That’s what MarketSmart’s system and services were built to do, and we do it so well that we guarantee a 10:1 return on your investment. Yes, that’s not a typo – a 10:1 ROI guarantee.

NOTE: This is not traditional prospect research. We call it engagement fundraising. Book a free demo today to learn more.

Second, you must understand what makes first-generation wealthy people unique from other affluent donors. You must learn how to connect with them around the four primary core values of first-generation wealthy families: modesty, agency, freedom, and the experience of being a lone ranger.

The four primary core values of first-generation wealthy families.

Value #1: Modesty

Another study referenced in the Leadership Story Lab report examined myths about the wealthy. For first-generation wealthy families in particular, these perceptions contrast greatly with how the wealthy view the world.

For example, a popular belief about the wealthy is that they like to spend lavishly on luxurious items like jewelry and cars they don’t need. Only 18% of marketers surveyed believed wealthy people consider those things a waste of money. However, 48% of wealthy people in the study said they considered those sorts of purchases wasteful.

Another myth about the wealthy is that they place a high value on the status afforded by their wealth. 55% of the marketers in the study reported believing this, yet only 11% of wealthy people said they want everyone to know they are wealthy. (Interesting how closely that figure aligns with the 8% who inherited all their money.)

The point is, especially among newly wealthy families and donors, most prefer to continue living modestly with a middle-class lifestyle and approach to money. This often holds true even when they have tens of millions in assets.

These folks admit they fit the definition of wealthy, but they don’t identify as such.

Take a look at Warren Buffett. He’s worth over $100 billion, yet he still lives in the same modest home he bought over six decades ago.

Folks like Buffett avoid flashy behavior. They take pride in how far they’ve come from what are frequently fairly humble childhoods. They have known how it feels to not have enough.

When around groups of more stereotypical wealthy people (even though those are a minority among the wealthy), newly wealthy people report feeling out of place, like strangers in a new land.

And they are quite concerned about how their wealth will affect their children. They recognize how hard they had to work to get where they are now and wonder how they can impart that to their kids.

This desire to live modestly even when one has great wealth leads many to avoid flashy and glittery fundraising events where all the well-off folks (and pretenders) hobnob with each other while giving their money away.

As a gift officer and fundraiser, connecting with a person like this — again, 68% of wealthy people — won’t happen if you presume most of them want recognition, bragging rights, notoriety, and all the rest. This type of person prefers to blend in and not show off their wealth. If you approach them presuming they want all the glory, you will turn them off.

Even more, this modesty is what leads many to conceal their wealth. Several people in the study said they don’t tell anyone the full extent of their assets. They hide it. Why? Because they don’t want to be seen and judged based on how much money they have, but on their values, work ethic, and experience.

This is one reason it’s difficult to identify these newly wealthy families. They’re hiding in plain sight.

Value #2: Agency

First-generation wealthy people have agency, a sense of control over their lives, and a feeling that they can affect the future.

This is a core characteristic that drives most newly wealthy people. Their agency compelled them to earn their money through their own hard work and manage it differently than someone who inherited all or most of it.

One interviewee explained, “Everything could fall apart tomorrow. If I’m ever left with a backpack and a pair of tennis shoes, I could get along. I don’t know if my kids know that about themselves.”

They think about how far they have come, and that the people who knew them early in life would have never thought it possible they could make it this far. They often apply that same ethos to other aspects of life, including philanthropy.

First-generation wealthy donors may believe they can apply their business wisdom and tireless work ethic to nonprofits. This sometimes leads to friction as they attempt to work with nonprofit leaders and administrators as well as fundraisers.

As we all know, what works in the business world sometimes works in the nonprofit world, but frequently does not. That can be hard for newly wealthy donors to wrap their minds around. That means you need to be patient with them and take more time to understand their perspective.

That doesn’t mean you give them everything they ask for, but it does mean you don’t minimize or shut down their take on how your organization is being run.

One wealthy subject in the study even commented, “I’m not a very good board member. I see operational weaknesses fairly quickly and want to fix them.”

Over time, they realized that this approach doesn’t always align with how nonprofits operate.

So while you might want newly wealthy donors to bring their passion and experience to your work — perhaps as a board member — recognize that this may not always be an easy relationship.

Value #3: Freedom

More than possessions and status, what newly wealthy families like most about wealth is the freedom it provides. They can send their kids to the college of their choice, find the most ideal educational opportunities, provide cultural and travel-based learning experiences, and respond to setbacks.

For them, wealth brings freedom, empowerment, and opportunity.

As one wealthy person in the study put it, “Money doesn’t buy you happiness, but it does buy you options.”

Newly wealthy families and donors want to use their wealth to influence the world for their family’s benefit as well as for the benefit of others.

When reaching out to newly wealthy donors, you’ll do well to spend time thinking about ways to give opportunities to them and their families, rather than just perks, gift bags, and other more shallow expressions of wealth.

Newly wealthy donors are very concerned about how to teach their children the value of hard work. In fact, it’s probably their single greatest worry. You might be able to help solve that problem if you get creative. Come up with ways for their children – whether kids or adults – to volunteer. Help them get involved with your work and get their hands a little dirty. These newly wealthy parents will probably jump at that chance.

And your organization would benefit, because now this family will be intimately involved with your work. In addition to becoming long-term financial partners, you’ll also benefit from their practical help and commitment.

Value #4: Lone Ranger

The last core value of newly wealthy donors isn’t as much a value as it is an experienced reality.

Many of the people in this demographic have experienced, with a fair amount of regret, the loss of friendships and key relationships, even with other family members.

Think about it: If you grew up with a bunch of friends, and one of those friends ended up building a nine-figure business while the rest of you worked conventional jobs, that ultra-successful friend just isn’t going to fit in as well.

The wealthy person in this situation has discovered this to be a hard truth and unforeseen consequence of building great wealth for the first time in their family.

Now, it’s easy for the rest of us to sit back and judge that feeling, because look at all the money they have! Break out the tiny violin!

But loneliness is loneliness, and it never feels good to lose friendships or family relationships that were in place for decades before.

Many newly wealthy families find they have no one in their lives at all with whom they can be fully transparent regarding their wealth. They struggle to relate to people at family get-togethers or high school reunions.

They are not used to thinking or viewing the world from a perspective of wealth. To them, they are still middle or even lower-middle class in some cases. They view trust-fund babies the same way the rest of us do, but when their friends start viewing them that way, they don’t know how to respond.

As mentioned at the outset, no one in the study could recall talking with anyone from a nonprofit about their wealth. In fact, all 20 newly wealthy families commented that this was the first time they had reflected on their wealth with anyone outside their immediate families.

By and large, they’re not talking to financial advisors, because most of them believe they can handle their money on their own. That’s the entrepreneurial value popping up again.

What You Should Do With This Information

Major gift officers are perfectly positioned to become a sort of confidante to these newly wealthy donors.

You are the kind of person they should have in their lives. They yearn for your engagement, guidance and counsel.

But you must be trustworthy. You must understand how they view the world and how these four values have shaped their lives and perspectives.

You must engage the newly wealthy donor in spite of their modest-looking lifestyle.

Once you do that, you can become that external trusted person with whom they feel comfortable talking about their wealth and all the options and opportunities it can bring them and their family.

Do you see how all four of these values intersect with each other?

Engage Newly Wealthy Donors the Right Way

As you have seen, the key step in all of this is to engage newly wealthy donors so you can understand them better.

Remember that $3 trillion expected to be given to nonprofits over the next ten years? Turn off newly wealthy donors by making poor assumptions about them, and you will miss out.

Engage them first with tech-enabled donor discovery, and you can approach them in a way they are very unused to but secretly long for.

MarketSmart’s system was built for this exact purpose: to qualify, cultivate, and prioritize the wealthy donors from within your donor lists and databases.

And as mentioned before, our system does this so well that we give a 10:1 ROI guarantee to all our customers. Schedule a free demo today to see how it works.

Related Resources

- Top 10 Tips for Landing More Meetings Report

- 7 big reasons why capacity is so hard to uncover (how the rich hide their wealth)

- Don’t survey your donors unless you have cultivation ready to go

- The 8 core components of engagement fundraising and why you desperately need them

LIKE THIS POST? PLEASE SHARE IT! YOU CAN ALSO SIMPLY LEAVE YOUR THOUGHTS BELOW.

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!