We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

Why people who say your non-profit should operate like a for-profit are wrong

Giving is different from buying

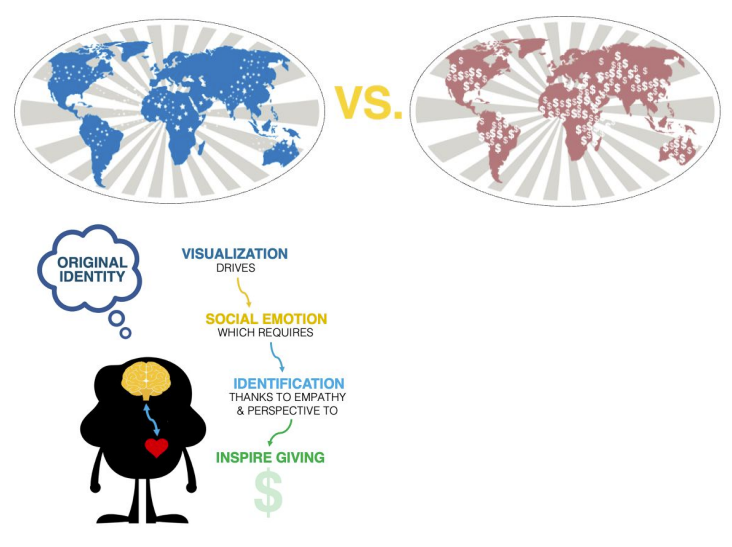

Charitable giving comes from “story world.” Effective fundraising story triggers visualization producing social emotion. This is the engine that drives giving.

But story world isn’t the only world. There’s also “commerce world.” Commerce world is all about accounting, contracts, and complexity. These can also be part of a giving decision. But they’re not the engine. These act only as a brake on giving.

Story world and commerce world are different. The rules in one world don’t apply to the other. Giving comes from story world. Thus, giving decisions often won’t match the rules of commerce world.

Investments in commerce world

Consider this business proposal: A new partnership will build a $100 million apartment complex. You’re thinking about buying 1% ownership for $1 million.

Would you care what part of the construction your $1 million would purchase? Would you demand, “I want my money to be spent on plumbing, but not on architecture fees!” No. Would such a demand even make sense? Also no. Asking which part your money would be used for is silly. It’s silly because money is fungible. Your dollar is the same as any other.

You would care about the project’s total cost. Unneeded cost would make your investment less profitable. But you wouldn’t care about assigning your dollars to any particular expense.

This makes sense. It makes sense in commerce world. But it’s not how fundraising works.

Investments in story world

In fundraising, people behave differently. Fundraising doesn’t live in commerce world. It lives in story world.

In story world, dollars are magical. They are characters in a fantasy drama. Some dollars are assigned to compelling roles. (Maybe your dollars buy the apartment’s fire alarm. They play the role that saves sleeping babies!) Others are not. (Maybe your dollars only pay for debt charges.) In story world, the project’s total cost isn’t all that relevant. What matters is that your dollars play a compelling role.

Fundraising is not commerce world: Experiments

Donors should “invest” their charitable gifts wisely. They should care about efficiency. Experiments show they often don’t.

In a lab experiment, some donors received positive financial reports about a charity. These proved the charity’s efficiency. The result? These “did not translate into increased actual giving.”[1]

In another experiment, donors could give to charities. However, the charities were unknown to them. But donors could access the charities’ financial efficiency details. What happened? “[T]he majority of actual donors were unwilling to obtain this information.”[2]

This was true even if

- The information was easy to get

- The donors were trained in business management

- The donors didn’t know the name of the charity they were giving to, or

- The donors were told the information was important “to donate their resources more efficiently.”

This lack of interest matches the lack of positive impact of such information. A meta-analysis, combining results from many studies, found “no positive effects at all for providing people with information about charity efficiency or effectiveness.”[3]

hbspt.cta.load(1716178, ‘7eeb5c86-5a5a-4beb-8181-e2373c14d969’, {“useNewLoader”:”true”,”region”:”na1″});

hbspt.cta.load(1716178, ‘7eeb5c86-5a5a-4beb-8181-e2373c14d969’, {“useNewLoader”:”true”,”region”:”na1″});

In one experiment, some donors learned that their selected charity’s overhead ratios were better than they expected.[4] The result? A third of these donors actually reduced their giving. Donors argued that they, “Give less but give smart.” (They got the same charitable impact with fewer dollars.)

That’s what happens in lab experiments. What happens in the real world? One field experiment tested more than 8,000 appeal letters. Some people got an appeal letter. Some got the same appeal letter plus a second page including positive financial information. (For example, 92% of charity funds were spent on program services.) The result? Adding this information reduced the likelihood of giving.[5]

Apparently, donors don’t give to financial efficiency. They don’t even want to read about it. Positive financial information doesn’t help.

However, negative financial information can still hurt. Some experiments show that donors will avoid projects or charities with higher overhead.[6] Math isn’t the engine for giving, but it can be the brake. This is true. Unless. Unless we change the story.

Fundraising is story world: Experiments

Avoiding high overhead projects or charities matches commerce world. Wise donors should select efficient charitable investments. High administrative costs might reflect lower efficiency.

But experiments show something different. Donors are not always averse to high-overhead projects or charities. They just don’t want their dollars to be spent on overhead.[7] If their dollars are spent on overhead, then overhead is a problem. If other donor’s dollars pay for it, then overhead isn’t a problem.

What matters is not the project’s efficiency. What matters is their donation story. Of course, assigning their dollars to the more exciting parts doesn’t change the project’s efficiency. But it does make their donation story better.

Other experiments found other story solutions.[8] One found that paying for overhead wasn’t a problem if the words changed. Just avoiding the word “overhead” helped.[9] So did replacing “overhead” with “overhead to build long-term organizational capacity.” It wasn’t about the numbers. It was about the story.

Of course, this makes no sense in commerce world. The study authors noted, “From a rational accounting perspective, this distinction should be irrelevant, but by framing the connection between the donor’s gift and the resulting benefit differently, although the objective benefit remains the same, the tangibility of the benefit is viewed differently (James, 2017).”[10]

- Another experiment looked at student giving to a campus synagogue.[11] The synagogue had expenses for

Prayer books and religious books - Electricity, cleaning, and food

Both types of expenses were necessary. But when gifts paid for the first type of expense rather than the second, donations were four times larger. Of course, donors didn’t want a dark and dirty synagogue. They just wanted someone else’s money to pay for that boring stuff.

In commerce world, a dollar is a dollar. But in story world, donors want their dollars attached to the interesting parts of the story. This is true not just for how its use is described. It’s true for when the gift is made. Donors are more willing to give money that helps start[12] or finish[13] a fundraising campaign. Starting gifts tell a “pioneer” or “leadership” story.[14] Ending gifts tell a “victory” or “finish line” story.[15]

In reality, money is fungible. A dollar is a dollar. A dollar given in the middle isn’t any more or less efficient that one given earlier or later. A project costs what it costs. Efficiency doesn’t change if some dollars are assigned to one part or another. It doesn’t change if an expense is described with different synonyms. These are realities. But they’re realities from commerce world, not from story world. Giving comes from story world.

Fundraising is story world: Academic theory (anthropology)

Issues that make no sense in commerce world can be key in fundraising. This distinction between worlds is not superficial. Philanthropy operates in a separate world from commercial exchange. It always has. A century ago, anthropologist Marcel Mauss studied gifting in indigenous cultures. He explained, “We have repeatedly pointed out how this economy of gift exchange fails to conform to the principles of so-called natural economy or utilitarianism … money still has its magical power and is linked to clan and individual.”[16]

In other words, giving is “magical.”[17] It lives in the world of story, often in the fantasy genre. These motives for gifts, Mauss explains, “are not to be found in the cold reasoning of the business man, banker or capitalist.”[18]

It’s no surprise then that economic theory took some time to adapt to this reality.

Fundraising is story world: Academic theory (economics)

Economic theory in philanthropy started with a model from commerce. This was called the public goods model.[19]

In this approach, donors wanted only the charitable outcome. They wanted a new park or less homelessness. They didn’t care if they personally caused the change or not. Ideally, someone else would give instead of them. That way they could enjoy the outcome without paying. Although attractive to economists,[20] this model had a problem. It often didn’t match actual human behavior.

This led to the “warm glow” model of giving.[21] This model added the idea that donors enjoy the act of giving. This allowed for the opposite extreme. A donor could enjoy giving even if their gift didn’t change anything.

More recently, a third model described “impact philanthropy.”[22] In this approach, donors care about their “perceived impact.” They want to personally make a difference. But the calculation of this impact is not objective.[23] It changes with various framings, descriptions, and temporary allocations. In other words, impact is based in story.

Thus, even economists have had to move beyond the cold reasoning of market-exchange models. Even they have had to adopt fuzzier concepts like “warm glow” and “perceived” impact.

Two worlds

Commerce world cares about accounting and efficiency. And rightfully so. But fundraising doesn’t live in commerce world. Fundraising lives in story world. Accounting can confirm or contradict a social-emotional story. But it can’t create it. Effective fundraising doesn’t start with accounting. It starts with story.

Footnotes

[1] Buchheit, S., & Parsons, L. M. (2006). An experimental investigation of accounting information’s influence on the individual giving process. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 25(6), 666-686.

[2] Id.

[3] Bergh, R., & Reinstein, D. (2021). Empathic and numerate giving: The joint effects of victim images and charity evaluations. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(3), 407-416. (“However, we found no positive effects at all for providing people with information about charity efficiency or effectiveness, with reasonably tight confidence intervals on this null effect in our meta-analyses (similar results were also obtained with other analytic strategies, see Supplementary Materials).”) See also, Becker, A. (2018). An experimental study of voluntary nonprofit accountability and effects on public trust, reputation, perceived quality, and donation behavior. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47(3), 562-582. (“… externally certified voluntary accountability demonstrates higher reputation and perceived quality among nonprofit organizations, but not relating to donation behavior”); Berman, J. Z., Barasch, A., Levine, E. E., & Small, D. A. (2018). Impediments to effective altruism: The role of subjective preferences in charitable giving. Psychological Science, 29(5), 834-844. p. 834 (“We found that even when effectiveness information is made easily comparable across options, it has a limited impact on choice.”).

[4] Butera, L., & Horn, J. (2020). “Give less but give smart”: Experimental evidence on the effects of public information about quality on giving. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 171, 59-76. (Note that in this experiment donors were to tell others about their gift and their charity’s overhead ratios, making both public.)

[5] The appeal letter recipients were randomly assigned to receive 1) an appeal letter only, 2) the appeal letter with a second page showing positive financial/accounting information, e.g., 92% spent on program services, 3) the appeal letter with a second page showing positive program accomplishments, or 4) the appeal letter with both additional pages. Overall, the addition of the positive financial information (letters 2 and 4) resulted in a decreased share of recipients making a charitable gift, lowering the share of those donating from 1.27% to 1.04%, precisely opposite of the result we would expect if donors made such decisions based upon financial and accounting operational efficiency factors. Parsons, L. M. (2007). The impact of financial information and voluntary disclosures on contributions to not‐for‐profit organizations. Behavioral Research in Accounting, 19(1), 179-196.

[6] Tinkelman, D., & Mankaney, K. (2007). When is administrative efficiency associated with charitable donations? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(1), 41-64. This contradicts findings from, e.g., Steinberg, R. (1986). The revealed objective functions of nonprofit firms. RAND Journal of Economics, 17, 508-526; Frumkin, P., & Kim, M. T. (2001). Strategic positioning and the financing of nonprofit organizations: Is efficiency rewarded in the contributions marketplace? Public Administration Review, 61, 266-275.

[7] Gneezy, U., Keenan, E. A., & Gneezy, A. (2014). Avoiding overhead aversion in charity. Science, 346(6209), 632-635.

[8] For example, one experiment found that high overhead wasn’t a problem if it was accompanied by other positive accounting information. When high overhead was reported 46% donated. When no overhead information was reported 70% donated. But when high overhead was reported along with information emphasizing the organization’s outstanding accounting transparency 77% donated. Accompanying high overhead information with other positive information about impact also helped, but not as much. In that case 63% donated. See Tian, Y., Hung, C., & Frumkin, P. (2020). Breaking the nonprofit starvation cycle? An experimental test. Journal of Behavioral Public Administration, 3(1), 1-19.

[9] Charles, C., Sloan, M. F., & Schubert, P. (2020). If someone else pays for overhead, do donors still care? The American Review of Public Administration, 50(4-5), 415-427.

[10] Charles, C., Sloan, M. F., & Schubert, P. (2020). If someone else pays for overhead, do donors still care? The American Review of Public Administration, 50(4-5), 415-427, 418. Citing to James, R. N., III. (2017). Natural philanthropy: a new evolutionary framework explaining diverse experimental results and informing fundraising practice. Palgrave Communications, 3(1), 1-12.

[11] Arbel, Y., Bar-El, R., Schwarz, M. E., & Tobol, Y. (2019). To what do people contribute? Ongoing operations vs. sustainable supplies. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 80, 177-183.

[12] Reinstein, D., & Riener, G. (2012). Reputation and influence in charitable giving: An experiment. Theory and Decision, 72(2), 221-243.

[13] Cryder, C. E., Loewenstein, G., & Seltman, H. (2013). Goal gradient in helping behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(6), 1078-1083; Kuppuswamy, V., & Bayus, B. L. (2017). Does my contribution to your crowdfunding project matter? Journal of Business Venturing, 32(1), 72-89.

[14] Called the “influencer” effect in Reinstein, D., & Riener, G. (2012). Reputation and influence in charitable giving: An experiment. Theory and Decision, 72(2), 221-243, 222.

[15] Called “goal gradient” motivation in Cryder, C. E., Loewenstein, G., & Seltman, H. (2013). Goal gradient in helping behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(6), 1078-1083

[16] Mauss, M. (1966/1925). The gift: Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. (Trans: Ian Gunnison). Cohen & West Ltd. p. 70.

[17] See discussion in Hornborg, A. (2016). Agency, ontology, and global magic. In Global Magic (pp. 93-111). Palgrave Macmillan.

[18] Mauss, M. (1966/1925). The gift: Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies. (Trans: Ian Gunnison). Cohen & West Ltd. p. 73.

[19] This is often referred to as “pure altruism.” However, the implications of the model result in behavior that is often the opposite of what a lay person would call altruistic, so I avoid using this term.

[20] This approach had wonderful theoretical advantages for mathematical model building. Donations could be treated like any other consumer purchase. Donors maximize their own benefit, i.e., their own consumption of the public good, while minimizing their personal costs. Thus, the models were mathematically tractable. (In other words, they could use calculus to identify a maximizing solution.)

[21] Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal, 100(401), 464-477.

[22] Duncan, B. (2004). A theory of impact philanthropy. Journal of Public Economics, 88(9-10), 2159-2180.

[23] More precisely, the mathematical model of impact philanthropy allows for multiple methods of estimating impact that specifically ignore various objectively true mathematical realities. After describing the power of gift targeting (i.e., gift restrictions) the author explains, “if a donor calculates impact by incorporating the changing gifts of others, then targeting a gift may not increase his or her utility.” Elsewhere the author explains, “Fully incorporating the response of others when calculating a gift’s impact suggests that a donor receives no pleasure from personally helping someone that would have been helped anyway.” He finds such a suggestion implausible. Duncan, B. (2004). A theory of impact philanthropy. Journal of Public Economics, 88(9-10), 2159-2180.

Related Resources:

- Donor Story: Epic Fundraising eCourse

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- How to Reduce the ‘Cost’ of Philanthropy So Major Donors Give More

- 4 Reasons Why Fundraisers Think Storytelling Matters

LIKE THIS BLOG POST? SHARE IT AND/OR LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!