We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

The Power of Heroic Philanthropy: Understanding Donor Motivations

Something’s missing. You might have noticed. The last few posts played the primal-giving game.[1] But they didn’t focus on heroes. Now, it’s time to get back to the “one big thing” in fundraising: Advance the donor’s hero story.

The heroic donation is an ideal. It’s an extreme form of philanthropy. The principles from the primal-giving game can still apply. But the game must change. It must become more extreme.

Extreme outcomes

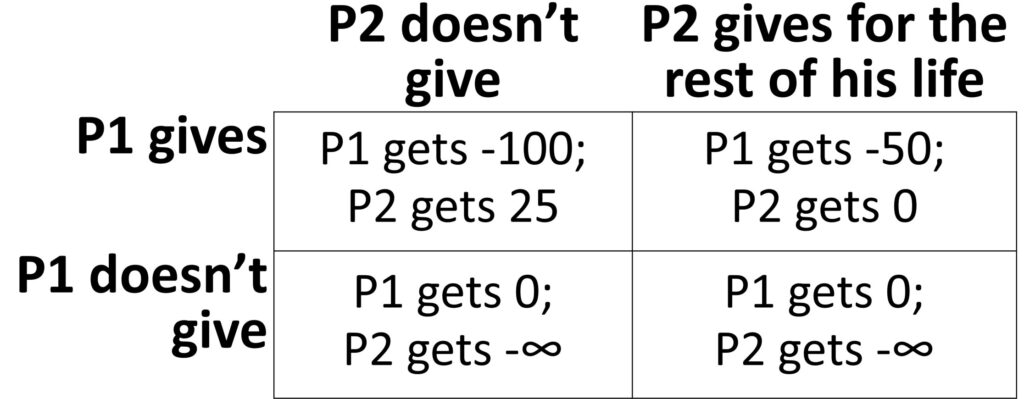

Suppose I am Player 1 with these payoffs:

My gift has a high impact. If I don’t give, the other player gets -∞ points. He dies. But my gift is costly.

Reciprocity is possible. But it can’t justify the gift. Even with the other player’s lifetime of return giving, my result is still negative. (Here, the gift costs 100 points. We might interact 25 more times. Each time he might benefit me 2 points. But 25 X 2 is only 50. 50 points is still less than the 100-point cost of the gift.)

In this game, there is only one rational move for me. Don’t give.

A new problem

Now, suppose we each face 50/50 odds of being either Player 1 or Player 2. Still, if Player 1 acts rationally, he won’t give. Whoever ends up as Player 2 will die.

Is there a better alternative? Yes. We could make a “mutual insurance” pact. We could both agree to give in a time of crisis. We could agree to support the other in an emergency, even if it were personally harmful. We would both survive.

Here’s the problem. No courts enforce these agreements. At the crisis point, giving is always a bad idea. Cheating is always the logical choice. This isn’t just a dilemma in the game. It’s a key issue in natural selection.

A new solution

In the primal world, survival often depended on a special type of reciprocity.[2] This was not the transactional reciprocity of market exchange. This was friendship reciprocity. It was used only among close friends and family.

Friendship reciprocity was mutual insurance. In time of need, a friend would help. This happened even if the help could never be fully paid back. This reciprocity was un-transactional.

Transactional reciprocity was fine. If you were rich and times were good, it might be all you need. But if everything fell apart, only friendship insurance could save you. Professors John Tooby and Leda Cosmides explain,

“For hunter-gatherers, illness, injury, bad luck in foraging, or the inability to resist an attack by social antagonists would all have been frequent reversals of fortune with a major selective impact. The ability to attract assistance during such threatening reversals in welfare, where the absence of help might be deadly, may well have had far more significant selective consequences than the ability to cultivate social exchange relationships that promote marginal increases in returns during times when one is healthy, safe, and well fed.”[3]

Losing the transactional reciprocity game was annoying. Losing the friendship reciprocity game was deadly.

The problem with the solution

So, the solution is simple, right? Just have as many friendship insurance relationships as possible. No. That doesn’t work.

The first problem is cost. Friendship insurance is mutual insurance. Getting unconditional help in a crisis is great. But giving it is costly.

The second problem is trustworthiness. Friendship reciprocity with someone who was able and willing to deliver in a crisis was critical to survival. Friendship reciprocity with someone who – at the moment of crisis – couldn’t or wouldn’t deliver?

That was costly and sometimes deadly.

Tooby and Cosmides explain,

“Although receiving the benefits of friendship reciprocity was critical, fulfilling the obligations of this mutual insurance was costly. Thus, maintaining successful friendships by projecting oneself – and accurately ascertaining a partner – as a valuable and “true” friend rather than a “fair weather” friend in advance of a crisis was an important and difficult task central to survival probability.”[4]

Separating powerful “true” friends from weak or “fair weather” friends meant life or death. But how could you tell the difference in advance of a crisis? And how could you convince others which kind of friend you would be in a crisis?

Heroism to the rescue

Heroism solves this problem. Heroism signals trustworthiness for a mutual insurance partner. In a crisis, a hero will save you. A hero is

- Able and willing

- To deliver transactionally unjustified protection

- In a time of crisis or need.

Heroism must be sacrificial. A sacrificial act signals willingness to protect in a crisis. It signals willingness without transactional justification.

If the act is not risky or costly, it doesn’t do this. If it’s self-interested or transactional, it sends the opposite signal. Sacrifice signals willingness to be a reliable friendship insurance partner.

Heroism must actually protect. Attempting, but failing, to protect another might signal willingness. But it doesn’t signal ability to protect in a crisis. Only a successful protector displays true friendship insurance reliability.

Heroic philanthropy

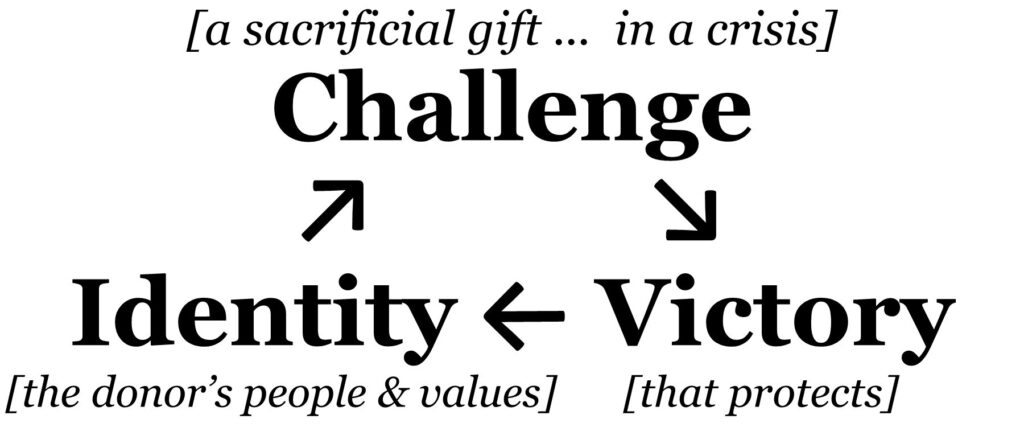

A hero displays sacrificial protection.[5] A heroic donation is this:

a sacrificial gift that protects the donor’s people or values in a crisis.

It includes the hero’s journey steps.

Heroic philanthropy in a crisis

Heroism signals trustworthiness as a friendship insurance partner. It shows reliability in a crisis. This is easy to demonstrate when there is real peril. But in a safe, modern world such extreme circumstances are rare.

What else can work? In some cases, philanthropy can. It can show the ability and willingness to deliver transactionally unjustified help and protection. In the right circumstances, it can do more. It can show this in an extreme or crisis setting.

Heroic philanthropy in experiments: Sacrifice

Suppose a charity could offer one of two ways to donate. One way is safe and easy. The other requires pain and effort. Logically, the first option will work better, right? Not necessarily.

In one study, people received money they could anonymously keep or share with a group.[6] Any donated funds were doubled. However, for some people, donating required a painful task. It required keeping both hands submerged in painfully frigid water for 60 seconds.

The result? Those in the painful donation situation gave significantly more money. They were more than twice as likely to donate all their money.

Mathematically this makes no sense. Adding pain to a donation should not result in more donations. But by the logic of heroism, this makes perfect sense. The painful contribution scenario created an opportunity for heroic donations. Giving everything matched the heroic opportunity. No surprise then, these 100% donations increased the most.

In another experiment, people could also donate to a charity and have their donation matched. For some, donating required attending a charity picnic. This was the “easy-enjoyable” condition. Others, instead, would have to complete a five-mile run. This was the “painful-effort” condition.

The result? People in the painful-effort condition offered to donate three times as much as those in the easy-enjoyable condition.[7] Again, requiring painful effort for the donation increased giving.

But there was a way to make this effect disappear. When experimenters offered both options at the same time, almost no one chose the painful-effort option. The researchers explained,

“The presence of an easy alternative for donating (the picnic) stripped away the meaningfulness of the painful-effortful contribution process (the 5-mile run).”[8]

When the painful-effort donation was the only way to give, it created the opportunity for a heroic donation. But when the painful effort became unnecessary, it was no longer heroic. It was pointless. It became meaningless.[9] The opportunity for heroism vanished.

Heroic philanthropy in experiments: Protection

Heroism must be sacrificial. But it must also protect. It must defend from a threat. This is different than helping those who aren’t in peril. This difference shows up in experiments.

In one, donors would have their gift matched. For some, donating required attending a picnic. For others it required a 30-hour fast. When the cause was famine relief, the results were as before. Those assigned to the painful-effort condition offered to donate twice as much.

However, this effect reversed when the cause changed. Instead of helping those in peril (famine relief) the cause was changed to building a park.[10] Now, donations were lower in the painful-effort condition. The heroism effect disappeared.

A park is nice. But it isn’t protecting anyone from peril. It provides no potential for a great victory. A gift might still be sacrificial. But it isn’t heroic.

In heroic philanthropy, the type of charitable project matters. Painful-effort giving didn’t work well for a new park. But it worked great whenever the cause protected others in peril. It worked when the cause was

- Tsunami victims [11]

- Hurricane Katrina victims [12]

- Victims of war and genocide,[13] or

- Starving children.[14]

A heroic gift displays both “sacrifice” and “protection.” Heroic philanthropy needs both parts. When the donation opportunity provides both parts (required sacrifice + protector role), donations are higher. When it is missing either part (pointless sacrifice or non-protector role), donations are lower.

Real world fundraising

Adding extreme circumstances to donations that protect others in peril works in the lab. But this isn’t just a matter of lab experiments. It shows up in real world fundraising. The ice-bucket challenge raised more than $115 million for the A.L.S. Association.[15] World Vision’s 30 Hour Famine – requiring extended fasting – has raised over $170 million.[16] Charity runs are ubiquitous.

But torturing your donors is not the point. (Unless you’re into that. In that case, some fundraising events even require walking barefoot on burning coals or broken glass.[17]) The point is that the behavior gives insight into core donor motivations.

Heroic donation opportunities can be compelling. But it helps to know why.

Knowing why shows the underlying rules. Knowing the rules helps. It helps in small-gift lab experiments. It helps in small-gift fundraising events.

Footnotes:

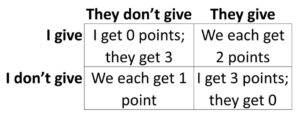

[1] This is known as the iterated prisoner’s dilemma game. For example, two players both face these payoffs:

where each must choose before knowing what the other will do.

[2] Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1996). Friendship and the banker’s paradox: Other pathways to the evolution of adaptations for altruism. Proceedings of the British Academy, 88, 119-144.

[3] Id. p. 132.

[4] Id.

[5] Philip Zimbardo, Professor Emeritus at Stanford and Founder/President of the Heroic Imagination Project, explains that heroes can be ordinary people “who engage in extraordinary actions to help others in need or in defending a moral cause, doing so aware of personal risk and loss, and without expectation of material gain for their action.” Zimbardo, P. (2017). Foreword. In S. T. Allison, G. R. Goethals, & R. M. Kramer (Eds.), Handbook of heroism and heroic leadership. Routledge. p. xxi.

Similarly, Franco, et al. (2011) define heroism as, “Heroism is the willingness to sacrifice or take risks on behalf of others or in defense of a moral cause.” In Franco, Z. E., Blau, K., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2011). Heroism: A conceptual analysis and differentiation between heroic action and altruism. Review of General Psychology, 15(2), 99-113. p. 113.

[6] Olivola, C. Y., & Shafir, E. (2013). The martyrdom effect: When pain and effort increase prosocial contributions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26(1), 91-105.

[7] Id. Experiment 4. In another test, Experiment 1, the average donation was nearly twice as much.

[8] Id. p. 95.

[9] The researchers statistically confirmed this meaningfulness explanation. Those offered only the painful-effort option rated the contribution as significantly more meaningful than those in the easy-enjoyable condition. This meaningfulness difference largely explained the difference in willingness to contribute.

[10] Olivola, C. Y., & Shafir, E. (2013). The martyrdom effect: When pain and effort increase prosocial contributions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26(1), 91-105.

[11] Id. Experiment 1A

[12] Id. Experiment 1B

[13] Id. Experiment 4

[14] Id. Experiment 5

[15] Rogers, K. (2016, July 27). The “Ice Bucket Challenge” helped scientists discover a new gene tied to A.L.S. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/28/health/the-ice-bucket-challenge-helped-scientists-discover-a-new-gene-tied-to-als.html

[16] World Vision. (2014, February 19). World Vision 30 hour famine rallies youth nationwide to fight hunger this weekend. [Website]. https://www.worldvision.org/about-us/media-center/world-vision-30-hour-famine-rallies-youth-nationwide-fight-hunger-weekend

[17] Birks, B. (2006, October 25). Sedgley firewalk. BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/blackcountry/content/articles/2006/10/24/fireandglass_feature.shtml

Haverhill News. (2004, October 21). Firewalkers blaze a trail for charity. http://www.haverhill-uk.com/news/firewalkers-blaze-a-trail-for-charity-1621.htm

Related Resources:

- Donor Story: Epic Fundraising eCourse

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- How transactional donor relationships kill generosity

- Dr. James explains the power of giving: why leading with a gift always wins

LIKE THIS BLOG POST? SHARE IT AND/OR LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!