We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

Dr. James explains why “No” often leads to “Yes”

Disaster!

We put in the work. We put in the planning. We carefully execute each step in the cultivation process. We thoughtfully craft and stage the fundraising ask. And, finally, we get the answer. And the answer is … “No.”

What do we feel? Disappointment? Devastation? Self-doubt? This emotional experience is all too common for fundraisers. And it’s bad. These bad emotions can lead to bad behaviors.

- It can make fundraisers avoid asking. (“Maybe I’ll stay in the office today. Someone’s got to choose the fonts for that new ‘branding’ effort.”)

- When they do bring themselves to ask, it can make them ask small and safe. (“What amount would be easy for this donor?”)

- Or it can make them callous. (“Cranking through enough ‘no’s’ just gets me closer to the next ‘yes.’ I am a high-volume sales machine! Just keep asking! Always be closing!”)

Flip the script

But what if the story was different? What if the “no” wasn’t the end of the story? What if the “no” was an essential part of the story?

The universal hero story contains several core elements. The prospective hero always faces a “call to adventure.”[1] This call says,

“Leave behind the small, self-focused, original world! Embark on a sacrificial journey to impact the larger world!”

And in that universal hero story, the answer to this call is always the same. It’s always “no.”[2]

“No” is the perfect start

Wait. What? How can that be? If the hero says, “No,” the story ends, right? Wrong. The hero eventually does accept the challenge. But this comes only later. First, the hero must reject the “call to adventure.”

Why? The rejection shows that the “call to adventure” is a serious challenge. It’s difficult. If the journey were easy, it wouldn’t be heroic. The “no” is essential to the story. But so is what happens after the “no.”

“No” is about what happens next

After the “no,” the effect of a compelling, heroic challenge continues. The ordinary, self-focused world feels a bit less captivating by comparison. Sometimes the hero’s circumstances change. Sometimes the guiding sage returns with a more compelling “call to adventure.” Only then does the “no” become a “yes.”

The hero’s guiding sage might be impressive like Obi-Wan, Morpheus, or Gandalf. Still, the initial “call to adventure” is met with a “no.” But the guiding sage does not disappear. The sage continues to play the role. The sage persists in advancing the hero’s journey.

In the hero story, the “no” is not the end. It’s just another step. Afterwards, the guiding sage’s role continues. The story cycle continues.

That’s fine for stories. But what does this look like in real-world fundraising?

Next steps in the real world

The donor says, “No.” Or “Maybe.” Or “I don’t know.” Now what?

The fundraiser’s role doesn’t change. The fundraiser is the donor-hero’s guiding sage. She helps the donor along the hero’s journey.

The fundraiser’s goal doesn’t change, either. The fundraiser advances the donor’s hero story. She continues the story cycle.

The next steps continue the role and the story. So, they’ll sound familiar. They’ll sound like the previous steps. The donor says, “No.” What’s next?

We begin by resuming the guiding-sage role.

1. Be silent.

Silence creates space for a donor to explain. It implies, “I am listening to you.”

2. Make a reflective statement.

This implies, “I hear you.”

3. Ask for permission.

Asking, “Can I ask you a question?” puts the donor in charge. Permission allows the fundraiser to resume the Socratic, guiding-sage role.

Next, we resume the story cycle.

4. Affirm the story connections.

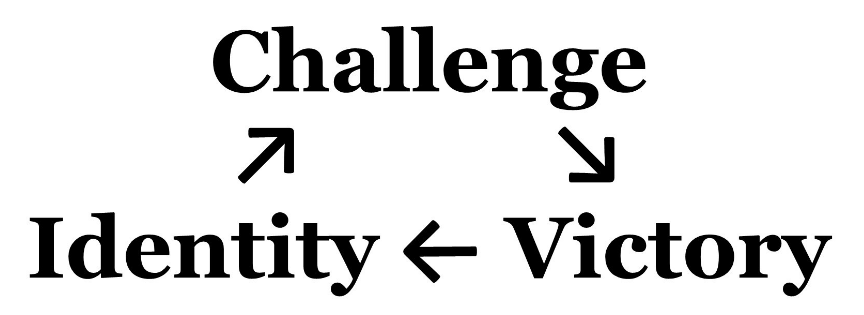

This continues the story. It connects Identity → Challenge → Victory → Identity. It shows why the donor wants to be part of this journey.

5. Diagnose the story barrier.

What is keeping the donor from saying “yes”?

6. Isolate the story barrier.

Confirm that this is the only barrier. This turns the “no” into a contingent “yes.”

7. Attack the story barrier.

Ask for permission to share some options. The options provide alternatives that address the barrier.

This isn’t a fundraiser-donor conflict. It’s not a dispute. It’s appreciative inquiry. It’s conversation. It’s sharing ideas about an external obstacle standing in the way of the donor’s hero story.

The guiding sage helps. She offers advice. She provides magical instruments. She helps the donor complete the hero’s journey.

The actual conversation may skip steps or change the order. But the goal is the same. Resume the role and resume the story. Let’s look at some example phrases for each step.

Part I: Resume the guiding-sage role

1. Be silent: “I am listening to you.”

After the ask the fundraiser must be silent. Everyone knows that. But silence also helps after the negative response. A donor says, “No,” or “I don’t know.” Don’t immediately start talking. Don’t fill the void. Just wait and listen. This silence can pull the donor to explain further. Remember, Socratic fundraising requires the donor to speak.

2. Make a reflective statement: “I hear you.”

The donor has spoken. We want to show that we have heard. We do that with a statement that reflects what the donor has said. It shows agreement, or at least empathy. Remember, this is not a dispute. We’re all on the same side.

The reflective statement is a transition. It can transition back to the ask. It can do this implicitly by going back to Step 1: Silence. It can do this explicitly by returning to make the ask again, this time with some added emphasis. Or, if the “no” is final, it can move forward to Step 3: Permission. These might sound like the following.

Suppose a donor says, “That’s a lot of money!” or “Wow! I don’t know.” Returning to Step 1 means making a reflective statement and then … silence. The statement might be simply,

- “Yes, it is.” Or,

- “I completely understand. This is a big consideration.”[3]

Or we can make a reflective statement and then re-ask. This time the ask should add some new emphasis. For example,

- “I know this is a big challenge. I wouldn’t ask except we need a strong female leader for this project.”[4]

- “I understand. Believe me, we don’t ask for this every day. You are one of the very few people we can turn to and ask for this important gift.”[5]

- “Perhaps they’ll say, ‘That’s more than anyone is this community has ever given.’ And you’ll tell the truth, replying, ‘That’s true, but then, this is the most important, largest campaign in our community’s history and a lot of people have given the largest gifts of their lives – I know I did.’”[6]

Each response begins with agreement. This resumes an advising role, not an arguing one. Agreeing that the request is large also matches the story. It highlights the heroic nature of the challenge.

Each response is followed by silence. The silence is powerful. It gets the donor to talk. Marc Pitman writes, “You might respond with a phrase like, ‘I can appreciate that …’ and let the silence fill the air. Watch what happens. Sometimes people just need to hear themselves explain why a gift is so important. It’s hard to be quiet at times like this but it’s crucial.”[7]

Ultimately, the answer may be a definite no. That’s OK. (It’s all part of the journey.) Once the donor is done talking, we’re ready to move to the next step. Once again, a reflective statement can start this transition. Socratic fundraising isn’t just about asking. It’s about asking, listening, and hearing. The reflective statement shows we’ve heard the donor.

3. Ask for permission: “Can I ask you a question?”

The next step justifies asking questions. It might sound like this:

- “I really appreciate you considering this. I want to learn a bit more about your feelings on this project. Do you mind if I ask you a question?”

- “Thanks for responding so clearly to my request. And I did hear what you said. I don’t mean to press you on the matter … but I feel I must ask you a question. Do bear with me …”[8]

As with other steps, this can be skipped. But asking for permission is powerful. It makes the donor feel in charge.[9] It gets them used to saying, “Yes.”[10] It creates acceptance for the questions to follow.

Part II: Resume the story cycle

After the “no,” we’ve resumed the Socratic role. We’ve listened. We’ve heard. We’ve justified asking questions.

Now it’s time to resume the story cycle. The story is the donor’s hero story. The hero story cycle progresses through[11]

Or simply,

We resume the story by reaffirming the story links.

4. Affirm the story connections

We begin the conversation with likely points of agreement. Our goal is to elicit the donor’s confirmation of giving motivations. We are coming alongside the donor. We are here to help the donor accomplish something meaningful to him.

We might start by confirming the identity connections with the cause or organization. This supports the link of Original Identity → Challenge. It might sound like this:

“You’ve been a supporter for so long and have done so much, I was certain you felt positive about our work and our vision. Do you still feel that same friendship and support?”[12]

We might confirm that the gift would make an impact. This supports the link of Challenge → Victory. For example,

“Are you concerned that the organization wouldn’t be effective at using this gift to make a difference in the lives of these students?”

We might confirm the meaningfulness of the gift’s impact. This supports the link of Victory → Enhanced Identity. For example,

“I remember the last time we met, you said that it was very important to you that … [insert the “victory” the gift accomplishes]. Has that changed for you?”[13]

Ultimately, we will get to the objection. This may be the price, timing, project, organization, or something else. But first we want to “clarify” what the objection is not. This re-establishes the donor’s motivation for the gift.

This also reframes the objection. The objection then becomes a barrier preventing the donor from accomplishing his goals. The goal might be

- “Your named scholarship fund,” or

- “The joy your gift will bring these patients.”[14]

The key idea is this. The goal is the donor’s goal.

The questions re-affirm the donor’s connections with the goal. They remind the donor why this goal is important to him. They remind him why this goal is part of his story.

5. Diagnose the story barrier

Next, we want to learn the details about the barrier. What’s the issue? Is it the cause? The organization? The project? The amount? The timing? We ask questions to learn.

But even if we already know, we still ask. We ask because getting the donor to state the barrier helps. It causes the donor to attach the “no” to the external issue. It’s no longer the donor’s “no.” It’s the obstacle’s “no.”

The guiding-sage fundraiser can then come alongside the donor to help. The two can work on this external problem together. As one fundraiser explains,

“By turning the objection into an objective, you’ve put yourself on the same side of the table as the other person. Now you both are working together to figure out how to help the donor make the gift. You’ve taken a possibly challenging problem and made solving it a team effort.”[15]

The questions can follow the familiar pattern. This starts with opening questions. These lead to follow-up questions. Finally, these end with reflective confirmation questions.

- Ask opening questions.

- Ask follow-up questions.

- Ask confirmation questions after reflective statements.

If the objection isn’t known, the initial questions might sound like this:

- “Can you share with me the reason or reasons why this is not something you want to do?”[16]

- “Can you tell me more about why you don’t think you can do this?”[17]

- “What are your concerns?”[18]

- Or for a “Maybe” response, “What factors are you weighing?”[19]

Once the reason is known, ask for elaboration. For example,

- “You said you ‘didn’t think you could swing that much.’ Tell me more about that. Is this an issue of timing, other obligations, liquidity, or something else?”

- “You said you couldn’t do this ‘right now.’ By ‘right now,’ what time frame do you mean?”[20] Or, “When would be the appropriate time for us to begin discussing your next gift?”[21]

- “You mentioned this project just isn’t for you. “What area of work would you be interested in?”[22]

6. Isolate the story barrier

We get the donor to state the objection. We ask for elaboration. We make a reflective statement. Then we request confirmation that we got it right.

But here’s the secret. We want a special kind of confirmation. We want a confirmation that this is the only barrier. This confirmation is powerful. It turns the “no” into a contingent “yes.” For example,

- “It sounds like you would like to invest in our school, but right now you can’t see how you might do it. Am I right about that?”[23]

- Donor: “I need to talk with my accountant. He’s not going to like it.” You: “What is important here today is that you would like this gift to happen.[24] If you want it to happen, we can work on the other issues together.”

- Donor: “I don’t think I can swing it.” You: “Maybe not, but I think you want to swing it. Am I right?”[25]

- [In response to a delaying or hyper-technical question] “That is another great question. Let me ask you, if I can answer this to your satisfaction, is this the last thing standing in the way of your making the gift?”[26]

7. Attack the story barrier

The barrier to the donor’s hero story has been defined. Now it’s time for the guiding sage to come alongside the donor to help attack that barrier. The guiding sage brings forth advice, wisdom, and magical instruments. The sage helps the hero complete the journey.

Obi-Wan gives Luke a light saber. Gandalf shows Bilbo where to find the ring. Morpheus teaches Neo “kung fu.” Dumbledore gives Harry Potter the invisibility cloak. The guiding-sage fundraiser comes alongside the donor to help solve the problem.

This could be a quick solution. Suppose the amount is too much. We respond by breaking the gift into a multi-year pledge. For example,

- “We’re not asking for a gift right now, just a pledge. As long as you can start your payments within the next three years, a pledge is just as good as a gift.”[27]

- If the person says, ‘I already have a pretty large commitment to the symphony to pay for,’ you can say, ‘I understand. Let me remind you that you will have a three-to-five-year window to pay off this gift.’”[28]

- They say: “$25K is too much. You say: “How about that over five years? $5K per year?”[29]

- “We’re not asking that you write a check today. Our pledge period goes up to four years, so it would be $125,000 each year.”[30]

Sometimes the quick solution doesn’t work. Then the guiding sage moves to more complex options. Here, the goal can change. It may no longer be to get agreement to make a gift. Instead, the goal may be to gain enough interest in a potential solution to get the next meeting. The next meeting presents the complex solutions.

Presenting solutions can follow the “feel, felt, found” pattern.[31] It ends with the request to discuss detailed options either now or at the next meeting.

- I understand how you feel. [This is a reflective statement.]

- Others like you have felt that way. [This begins a social norm.]

- Here is what they have found that worked. [This presents a solution idea with a social norm.]

In a conversation, the pattern might sound like this.

DONOR: [Not much excitement about this leadership or organization.]

YOU: I understand how you feel. Others who have felt the same way have decided to put specific instructions with their gift. That way they know exactly what their money is accomplishing. Would a permanent endowment funding the domestic violence outreach be of more interest to you?

DONOR: I would love to do this, but I’m on a fixed income. (Or I’m saving for retirement.)

YOU: I understand how you feel. Many of our donors have felt the same way. They have found that they can make a gift that pays them income for life. Or they can add a gift in a will that costs them nothing today. What are your thoughts about that?

DONOR: All my assets are tied up right now. The cash just isn’t available.

YOU: I understand. We work with many donors like you in this same position. It’s actually the perfect situation. The tax benefits are much better if you give before you’ve sold the asset. Would you mind if I put together some options for you? I think you might be surprised at what the numbers look like.

DONOR: I would make an estate gift, but all my planning is done. I don’t want to have to go through that again!

YOU: I understand. Many of our donors feel the same way. But they’ve found that the smartest way to make the gift isn’t by changing their will or trust documents. They just add the charity as a beneficiary to an IRA or 401(k). Anyone else who inherits that money pays income taxes on it. But not the charity. Would you mind if I showed you how easy it is to do this?

DONOR: [Not much excitement about this project.]

YOU: I understand how you feel. Others have felt the same way. They’ve found that other projects are a better fit for them. Do you mind if I share some of those? You might find one that really appeals to you.

The more solutions the fundraiser knows, the more likely she can continue the conversation. But the goal isn’t always to give a quick solution. It can be enough to reference that there are some possible solutions. This is followed by a request.

The request is for permission to share more detailed options. It might sound like this: “If you wouldn’t mind visiting again, I’d like to work with some experts and put together a few personalized options for you. There’s no obligation, but I think you’ll find some of them really interesting. Would your calendar allow us to meet on Tuesday the 15th at this same time?”

Agreement for the next meeting gives the donor more time to think. It gives the fundraiser more time to plan. It also justifies asking detailed questions to help build the specific proposal.

Why not just concede?

Among all these steps and strategies, one approach is missing. Don’t start by conceding. As Laura Fredricks advises, if a donor objects to the amount, “First and foremost, please do not say, ‘What did you have in mind?’”[32]

Why not? Admittedly, the donor’s decision is the donor’s decision. If he decides to give $1,000 instead of $10,000, then that’s what he’ll do. But the role of the guiding-sage fundraiser is to help the donor accomplish a heroic victory. It’s not to just settle for the comfortable “pat on the head” gift. Those gifts are fine. But they aren’t heroic.

If the donor isn’t interested in the stretch gift, then something is missing. The fundraiser’s role is to find out what that is. What’s the barrier? Is it the project, the charity, the timing, the amount? We want to work on it together. We want to overcome that barrier.

The immediate response is not to give up the victory. It’s not to happily trade the hero’s journey for a convenient “go away” gift. Why shouldn’t we simply concede? Because that’s not the role we’re playing. That’s not the story we’re advancing.

Notice the heroic themes in Laura Fredricks’s response to the “no,”

“[state] right up front that yes, this is a very large amount asked, something not done every day … The next response, “You are one of the few people we can turn to ask for this important gift,” will bolster your original statement and will let the prospect know that the organization views him or her as a treasured and model donor.”[33]

Of course, the proposed gift might not be possible. Even with all the guiding sage’s magical instruments, the gift might be simply beyond the donor’s capacity. That’s OK. But we want to get to that place at the end of this process, not at the beginning. And what happens then?

The hard “no”

Even with a hard “no,” the goal doesn’t change. The goal is still to advance the donor-hero’s journey. The goal is still for the donor to make a heroic gift. And because of the Socratic process, we know more.

We know more about the story connections. We know more about the story barriers. This can lead to crafting a better challenge for this donor. Or it can lead to leaving the challenge for a future day.

Not every “no” can be quickly flipped to a “yes.” But the truly heroic challenge is still compelling. If it fits with the donor’s identity, it’s compelling. If it promises a meaningful victory, it’s compelling.

Even after the “no,” this heroic challenge can continue to influence the donor. In the monomyth, the hero refuses the first call to adventure. But things change. Things can change for donors, too. Financial circumstances can shift. Businesses can be sold. Investments can go well. Inheritances can arrive. Estate plans can be revised. The opportunity to accept the compelling heroic challenge may arise again. Today’s “no,” can still become tomorrow’s “yes.”

I’m so sorry, you got a “yes”

Not every request is met with resistance. Sometimes the donor immediately says, “Yes.” What then? We thank the donor for the gift. We express gratitude for the impact the gift will have. We confirm the precise date, time, and manner of transfer. (A simple gift agreement sometimes helps.) And then, we stop. As the West Texas saying goes, “Once you hit oil, stop drilling.”

But a quick “yes” might show something else. Part of the story might be missing. If the hero doesn’t initially resist the “call to adventure,” was it really a heroic request after all? If the donor didn’t need to think about it, was it really a sacrificial gift? Did we really advance the donor’s hero story? Experienced fundraisers recognize this reality. One shares this,

“If they say ‘yes’ straight away when you ask for a specific amount, the chances are that you have not asked for enough.”[34]

The final ask

Whether the visit results in a gift or not, there can be one final ask. This ask is for referrals. It might sound like this:

- “Do you know other people that may be interested in learning about what we’re doing?”[35]

- “Can you name three friends/colleagues who might like to learn more about our organization or who might also be interested in serving as volunteers?”[36]

- “Who do you know that may be interested in our work? Would you send a note to introduce me, or arrange for us to do lunch? You like to entertain – how about a dinner party or reception? How about tagging along on a donor visit and sharing your experience with our nonprofit?”[37]

Plan to fail

In the monomyth, the hero first refuses the call to adventure. In advancing the donor’s hero story, a “no” is a typical part of the process. Understanding this means we plan for it.

So, for example, we don’t leave the ask until the end of the scheduled time. A “no” can be an excellent start. But the follow up is critical. And it takes time.

It also means that we emotionally plan for a “no.” It’s not a jolt. It’s not a cause for disappointment. It’s part of the journey.

Plan to fail: A professor story

I’ve been the dissertation advisor for many Ph.D. students over the years. These students have gone on to be faculty members at many universities. To succeed there, they must publish research in academic journals. A critical part of this success is planning to fail. How so? The publishing plan should be,

“I will submit to Journal A. Then, I’ll use the reviews from the rejection to improve the manuscript for Journal B. Then, I’ll use those rejection reviews to improve the manuscript for Journal C. And Journal C will publish the manuscript.”

Rejection becomes normal and expected. It’s a natural part of the process. It triggers immediate revision and resubmission.

What if instead the plan were to just publish in Journal A? Then things change. A rejection is devastating. Engaging with the negative reviews is emotionally painful. The revision hurts. It gets delayed. The manuscript sits on the desk. And “publish or perish” leads to job loss. Framing the rejection as part of the process – not some devastating aberration – helps. It leads to the right behaviors.

Plan to fail: A fundraiser story

In the same way, planning for the “no” is important for the fundraiser. If any single behavior separates the successful fundraisers (or researchers) it is this: persistence. Having the right story framework helps.

The right story emotionally supports the right behaviors. The “no” is not a source of pain. It’s an important step in the journey. It opens the door to important questions. It’s part of the process. It’s part of the story.

Conclusion

Making a compelling, heroic challenge is an accomplishment. It’s not every day that people receive an epic “call to adventure.” The ask can make a lasting impact even when the answer is “no.”

The “no,” is not a problem for the guiding sage. The sage resumes the story role. The sage resumes the story cycle. The sage persists. As the famous monomyth guiding sage Yoda explains,

“You think Yoda stops teaching, just because his student does not want to hear? A teacher Yoda is. Yoda teaches like drunkards drink, like killers kill.”[38]

Postscript: The scariest ask

The script for handling the fundraising “no” from Tony Soprano

YOU: … would you consider a gift of a million dollars to kick off the campaign for the Anthony and Carmelo Soprano Athletic Center at the St. Thomas High School?

TONY: [Laughter.] You’ve got to be kidding me!

YOU: [Silence… but you smile, reflecting his response.]

TONY: A million bucks! I don’t know what you’ve been smoking, but I want some!

YOU: OK, OK [Smiling], I understand. [This shows reflection.]

YOU: Help me out here. Do you mind if I ask a couple of questions to see where I got off track? [This asks for permission].

TONY: Yeah, I’m not giving you a million bucks. That’s where you ***ing got off track!

YOU: [Smiling.] I hear what you’re saying. [This shows reflection.]

[Now, you resume the story.]

Look, I know you’ve supported this school for years. Everyone in the community sees you as a leader at the school. We’ve been part of your life, and your family’s life for such a long time, so I’ve got to ask, have your feelings about the school changed? [This affirms the story. It shows Original Identity → Challenge.]

TONY: No, no. Look, the school’s a good thing. That’s fine. But I’m more of a ‘$20 bill in the G-string’ guy, not a “buy her a whole **ing house” guy, right?

YOU: I understand. Now, the people running the school … you’ve known Mrs. Smith for, what, 12 years? Do you feel like they would use the building in the right way to make the kind of impact you would want to see? [This affirms the story. It shows Challenge → Victory.]

TONY: Sure, these are good people. I don’t see them doing stupid things.

YOU: And this project – The Soprano Athletic Center – do you see that as making a real impact in our community here for a long time? It would have been a big deal for you when you were a kid growing up here, right? [This affirms the story. It shows Victory → Enhanced Identity.]

TONY: Oh, sure, it’s a good thing. Give the kids something to do instead of robbing or breaking stuff. But look, I’m not going to pay for this whole thing now. Maybe someday when I retire rich, I can write you that check.

YOU: So, it sounds to me like this is a gift you would want to make if you could, but the finances are just too much right now? [This diagnoses and isolates the story barrier.]

TONY: Yeah, that’s just the wrong price tag for me.

YOU: Now, you know this is a pledge that can be paid out over the five-year campaign. So, that’s $200,000 each year. Does that help at all? [This attacks the story barrier.]

TONY: I don’t know. That’s still a lot of cash.

YOU: Yes, it is. Let me ask you, have you ever thought about giving stocks or real estate instead?

TONY: [Gives a quizzical look.]

YOU: The reason I ask is that I work with a lot of folks in your situation. They want to make a really big impact with a great project, but the cost is too big of a barrier. So, here’s what they do. They get the government to pay for more of it by being smarter about giving.

YOU: Let me give you an example. Say someone has a building or some stocks worth $200,000 – the annual pledge amount for this project. But maybe they bought it for only $20,000. The problem is this. If they sell it, they don’t get to keep the full $200,000. Here in New Jersey, they might lose a third to the government in taxes. So, they actually walk away with only $138,000.

TONY: Tell me about it. Those taxes are a racket!

YOU: But if they donate it instead, they avoid all those taxes. And they still get the full $200,000 deduction off their income taxes. That deduction can save them up to 47 cents on the dollar.

YOU: So, if they sell the property, they net $138,000. If they donate it instead, they net up to $94,000. Their net cost is just the $44,000 difference between selling and donating. The school still gets a $200,000 gift. The tax benefits pay for the rest.

TONY: So, this thing. It works with a building, like a warehouse?

YOU: Sure, any assets that have gone up in value.

TONY: What about a business like an “entertainment establishment” or a used car dealership?

YOU: Definitely. I’d love to put together some ideas for you to look at. Just give me some examples of assets – what you paid, what they’re worth – no obligation. I know the Soprano Athletic Center seems like a reach right now, but I can work with our experts, put together a plan, and you just tell us what you think. Do you mind if we get together for a visit on Tuesday the 4th to look at some options?

TONY: I guess it wouldn’t hurt. Tuesday? …

Footnotes:

[1] See Chapter I, Section 1, “The Call to Adventure” in Campbell, J. (1949/2004). The hero with a thousand faces (commemorative ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 45-54

[2] See Chapter I, Section 2, “Refusal of the Call” in Campbell, J. (1949/2004). The hero with a thousand faces (commemorative ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 54-63.

[3] Levine, J. & Selik, L. A. (2016). Compelling conversations for fundraisers: Talk your way to success with donors and funders. Chimayo Press. p. 93.

[4] Melvin, A. (2020, October 7-9). Solicitation preparation: The keys to a successful ask. [Paper presentation]. Charitable Gift Planning Conference, online. p. 10.

[5] Fredricks, L. (2001). Developing major gifts: turning small donors into big contributors. Aspen Publishers, Inc. p. 116.

[6] Grover, S. R. (2006). Capital campaigns: A guide for board members and others who aren’t professional fundraisers but who will be the heroes who create a better community. iUniverse. p. 105.

[7] Pitman, M. A. (2008). Ask without fear! A simple guide to connecting donors with what matters to them most. Tremendous Life Books. p. 43.

[8] Panas, J. (2007, March 1). Fundraising’s four magic questions: Answer these and the gift is yours. Guidestar. [Blog]. https://trust.guidestar.org/fundraisings-four-magic-questions-answer-these-and-the-gift-is-yours

[9] Experimental research shows that increasing donors’ feelings of agency results in a greater willingness to donate. See, e.g., Xu, Q., Kwan, C. M., & Zhou, X. (2020). Helping yourself before helping others: How sense of control promotes charitable behaviors. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 30(3), 486-505. See also, Heist, H. D., & Cnaan, R. A. (2018). Price and agency effects on charitable giving behavior. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 77, 129-138.

[10] For a discussion of the positive effects of such repeated requests in pro-social decision making see Fennis, B. M., & Janssen, L. (2010). Mindlessness revisited: Sequential request techniques foster compliance by draining self-control resources. Current Psychology, 29(3), 235-246. Note that the current structure is combining an overall DITF sequence (large request is rejected followed by more attractive counter-offers) with this FITD step asking for permission to ask a question (easy initial request followed by more substantial request). For an example of FITD with charitable decisions see Bell, R. A., Cholerton, M., Fraczek, K. E., Rohlfs, G. S., & Smith, B. A. (1994). Encouraging donations to charity: A field study of competing and complementary factors in tactic sequencing. Western Journal of Communication, 58(2), 98-115.

[11] For a description connecting these steps to Campbell, J. (1949/2004). The hero with a thousand faces (commemorative ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 28, see footnote 3 in Chapter 1. Socratic fundraising theory: How questions advance the story.

[12] Panas, J. (2007, March 1). Fundraising’s four magic questions: Answer these and the gift is yours. Guidestar. [Blog]. https://trust.guidestar.org/fundraisings-four-magic-questions-answer-these-and-the-gift-is-yours

[13] Wohlman, J. (2020). Practice the ask and negotiation (part 3). [Video transcript]. Major and principal gifts course. University of California, Davis. https://www.coursera.org/lecture/major-principal-gifts/practice-the-ask-and-negotiation-part-3-bxhL5

[14] Fredricks, L. (2001). Developing major gifts: Turning small donors into big contributors. Aspen Publishers, Inc. p. 121.

[15] Pitman, M. A. (2008). Ask without fear! A simple guide to connecting donors with what matters to them most. Tremendous Life Books. p. 44.

[16] Fredricks, L. (2006). The ask: How to ask anyone for any amount for any purpose. John Wiley & Sons. p. 211.

[17] Id.

[18] Collins, M. E. (2017, Winter). The Ask. Advancing Philanthropy, 16-23, p. 22.

[19] Id.

[20] Fredricks, L. (2006). The ask: How to ask anyone for any amount for any purpose. John Wiley & Sons. p. 212.

[21] Stroman, M. K. (2014). Asking about asking: Mastering the art of conversational fundraising (2nd ed.). CharityChannel Press. p. 244.

[22] Managementcentre. (2016, March 11). 7 Steps of Solicitation [Website]. managementcentre.co.uk/fundraising/7-steps-of-solicitation/

[23] Wohlman, J. (2020). Practice the ask and negotiation (part 3). [Video transcript]. Major and principal gifts course. University of California, Davis. https://www.coursera.org/lecture/major-principal-gifts/practice-the-ask-and-negotiation-part-3-bxhL5

[24] Fredricks, L. (2001). Developing major gifts: Turning small donors into big contributors. Aspen Publishers, Inc. p. 117.

[25] Melvin, A. (2020, October 7-9). Solicitation preparation: The keys to a successful ask. [Paper presentation]. Charitable Gift Planning Conference, online, p. 10.

[26] Baker, B., Bullock, K., Gifford, G. L., Grow, P., Jacobwith, L. L., Pitman, M. A., Truhlar, S., & Rees, S. (2013). The essential fundraising handbook for small nonprofits. The Nonprofit Academy. p. 250.

[27] Grover, S. R. (2006). Capital campaigns: A guide for board members and others who aren’t professional fundraisers but who will be the heroes who create a better community. iUniverse. p. 105.

[28] Collins, M. E. (2017, Winter). The Ask. Advancing Philanthropy, 16-23, p. 22.

[29] Melvin, A. (2020, October 7-9). Solicitation preparation: The keys to a successful ask. [Paper presentation]. Charitable Gift Planning Conference, online, p. 11.

[30] Grover, S. R. (2006). Capital campaigns: A guide for board members and others who aren’t professional fundraisers but who will be the heroes who create a better community. iUniverse. p. 105.

[31] Ciconte, B. L. & Jacob, J. G. (2009). Fundraising basics: A complete guide. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 168; Panas, J. (2002). Asking: A 59-minute guide to everything board members, volunteers, and staff must know to secure the gift. Emerson & Church. p. 70. For examples of this technique in sales literature, see, Sobczak, A. (1995). How to sell more, in less time, with no rejection. Business By Phone Inc.; Weitz, B. A., Castleberry, S. & Tanner, J. F. (2009). Selling: Building partnerships. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill. For evidence that this improves long-term relationships with customers, see, Habel, J., Alavi, S., & Pick, D. (2017). When serving customers includes correcting them: Understanding the ambivalent effects of enforcing service rules. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(4), 919-941. Note that this approach is focused on empathy, emotion, and social relationship, matching a philanthropic context. For evidence that it works poorly in an unemotional, competitive, contract context such as when closing a sale with industrial buyers, see, Delvecchio, S., Zemanek, J., McIntyre, R., & Claxton, R. (2004). Updating the adaptive selling behaviours: tactics to keep and tactics to discard. Journal of Marketing Management, 20(7-8), 859-875.

[32] Fredricks, L. (2006). The ask: How to ask anyone for any amount for any purpose. John Wiley & Sons. p. 213.

[33] Fredricks, L. (2001). Developing major gifts: Turning small donors into big contributors. Aspen Publishers, Inc. pp. 116-117.

[34] Managementcentre. (2016, March 11). 7 Steps of Solicitation. Retrieved from managementcentre.co.uk/fundraising/7-steps-of-solicitation/

[35] Baker, B., Bullock, K., Gifford, G. L., Grow, P., Jacobwith, L. L., Pitman, M. A., Truhlar, S., & Rees, S. (2013). The essential fundraising handbook for small nonprofits. The Nonprofit Academy, p. 154.

[36] Greenhoe, J. (2013). Opening the door to major gifts: Mastering the discovery call. CharityChannel Press. p. 58.

[37] Pittman-Schulz, K. (2012, October). In the door and then what? [Paper presentation]. National Conference on Philanthropic Planning, New Orleans, LA. p. 14.

[38] Stewart, S. (2014). Yoda: Dark rendezvous (Star wars: Clone wars). Ballantine Books. p. 301.

Related Resources:

- Donor Story: Epic Fundraising eCourse

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- The Importance of Asking Permission to Ask More Questions

- Finally, the questions you should ask that have been proven to lead to gifts from wealth

LIKE THIS BLOG POST? SHARE IT AND/OR LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!