First: when we talk about cost, we’re not talking about fundraising expenses.

That’s not what this article is about. Rather, it’s about the fact that giving money away can feel costly to your supporters. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Next, here’s a quick recap of the previous post.

In the preceding post, I explained why wealthy people care about cost (even when it comes to philanthropy). Basically, I said, they’re not stupid! They didn’t get rich without caring about cost.

I also reminded you to have empathy for your top donor prospects. Just because they have a lot of money doesn’t mean they’re willing to toss it around foolishly. No! They want value in exchange for their money, and sometimes value comes in the form of lowered cost.

The bottom line is that many wealthy people don’t feel wealthy. Rather, 1 out of 5 people with $50 million or more feel extremely financially insecure and 1 out of 10 feel somewhat financially insecure.

I know, it’s hard to believe. But those feelings matter. They are real!

So what does that mean for you and your staff?

Since now you (hopefully) agree that wealthy people care about the cost of giving, you’ll want to determine how you and your colleagues can make the cost feel less onerous. After all, it’s how your donors feel about giving that matters. To them, perception is reality.

Thankfully, Dr. Russell James (the foremost researcher in the field) analyzed this and settled on five ways you can reframe cost so your supporters feel good and give more.

Reframing cost requires story

People are motivated more by stories than they are from a chart full of numbers. Stories elicit emotions, and emotions drive giving.

When you listen to your supporters’ stories and connect them to opportunities to realize the best versions of themselves, they lean in. But sooner or later, they think about cost.

That’s when you need to reframe whatever cost your supporters begin to take into account. Reframing can make the cost feel less painful, and that can change your fundraising results a lot.

For example, Dr. James says, “Suppose a person gives shares of stock for the first time. They learn that capital gains taxes are avoidable. From that point forward, the category becomes donation relevant. Whenever a sale [of stock] is contemplated, charity comes to mind.”

Information doesn’t help reframe costs; stories do

Information is inert. It lacks emotion. That’s why it fails to drive motivation.

But framing costs by sharing stories with your wealthy supporters about how you helped others like them lessens the cost of giving and engages their feelings. That motivates giving. Especially if your framed stories show how the other donors realized the best versions of themselves and found meaning in their lives through giving at reduced cost.

For instance, here’s something you might find yourself in a position to say: “[Insert Name] was able to create a legacy and live on in the minds of others while benefiting from a substantial tax benefit.”

Following a prologue to another donor’s story like that, you can elaborate on the story. “[Insert Name] told me she was delighted because she realized she could give more than she originally thought possible. We were able to set up a scholarship in her name.” As a result, the donor won a ‘victory’—an outcome—that benefitted her and so many others. Now that would be a story worth telling!

Donors then see that you helped someone like them attain tremendous value from their giving experience. Ultimately, that’s what most of your supporters are after—VALUE! They want a good deal because that’s how they’re wired. They care about cost because lower cost feels good!

You can help. But you’ve got to reframe cost through storylistening (giving them an opportunity to tell their story), and storytelling (recounting that people like them do things like this).

Objective and subjective cost reduction.

Dr. James says, “Subtraction lowers the total cost of giving. This can be objective. For example, tax benefits can do this. But it can also be subjective. Even with the same number, the feeling of cost can become less. This can happen when the cost is compared with different reference points. It can happen when the cost comes from different sources.”

He continues by saying, “Compared with routine disposable income purchases, a $1,000 gift can feel enormous. Compared with infrequent major purchases, it can feel reasonable. Compared with wealth, it can feel tiny. In all three cases, the cost is the same. But the feeling of the cost can change dramatically.”

That’s why he recommends (and MarketSmart agrees!) that you tell stories about how donors successfully use their assets to gain value. Usually the value they need is to feel like the hero in their own life story, and they want to attain that feeling at a reasonable cost.

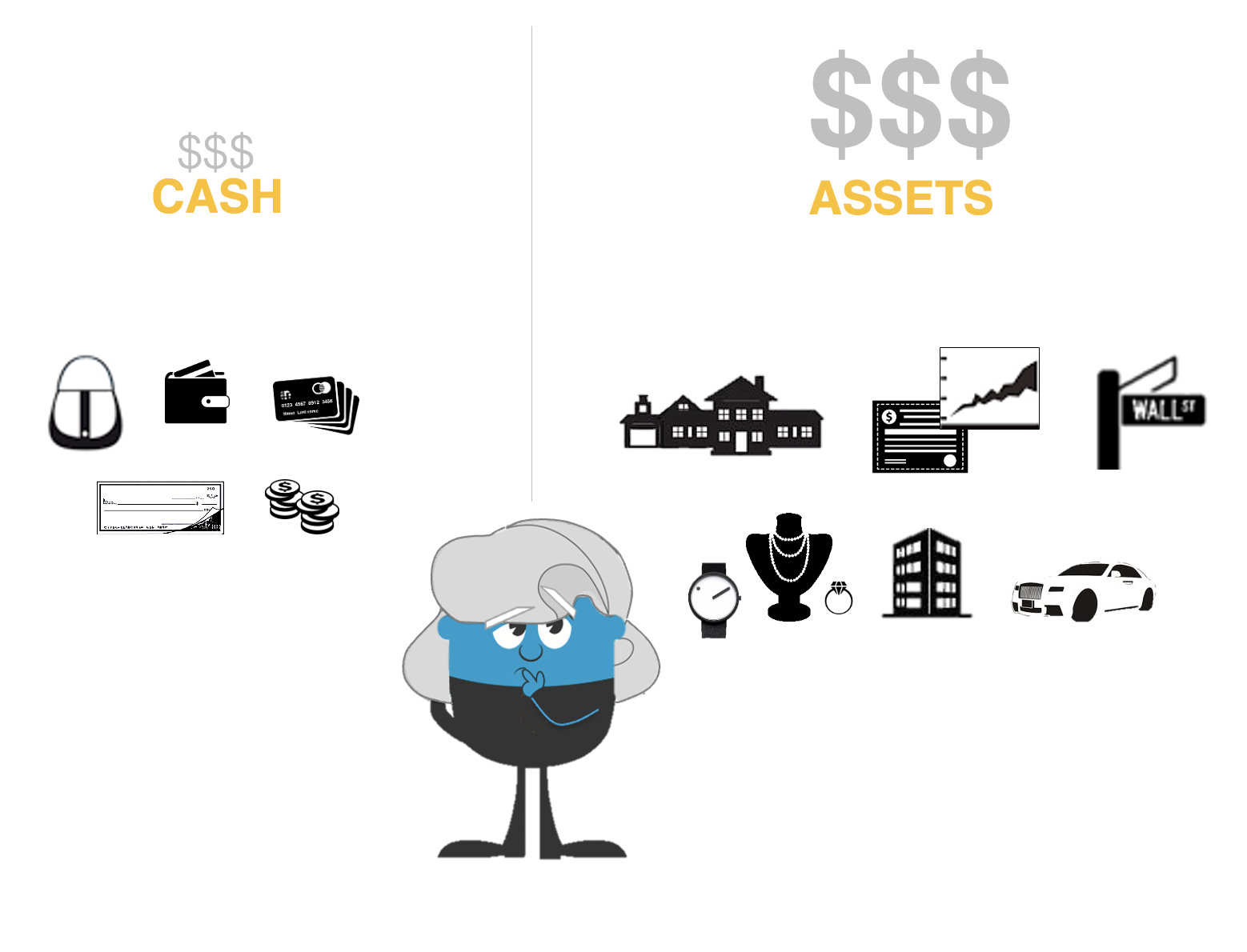

Begin by focusing on assets, not cash.

Giving cash feels like a loss to everyone. But giving from assets generally feels much less painful. Plus, many supporters experience a “windfall gain” feeling when they sell an asset. Afterward, they often feel a sense of abundance. At that time, giving more of it away feels less weighty. The cost feels less onerous.

Avoiding a loss can reduce cost too. For instance, when donors give from their IRA with a qualified charitable distribution (instead of taking the minimum distribution), they avert a loss. They feel good knowing that they circumvented the tax they would have had to pay on the minimum distribution income, especially if they didn’t even need that income in the first place (which is common among wealthy IRA donors).

At last, the 5 ways Dr. James recommends you lower costs to make your donors feel good.

1. Sequencing:

Without motivation, nothing else matters. So, it’s essential that you trigger motivation first from the social-emotional engine in your supporters’ minds. Worry about making a logical argument to overcome the cost barrier when the time is right.

The sequence matters and should never be reversed.

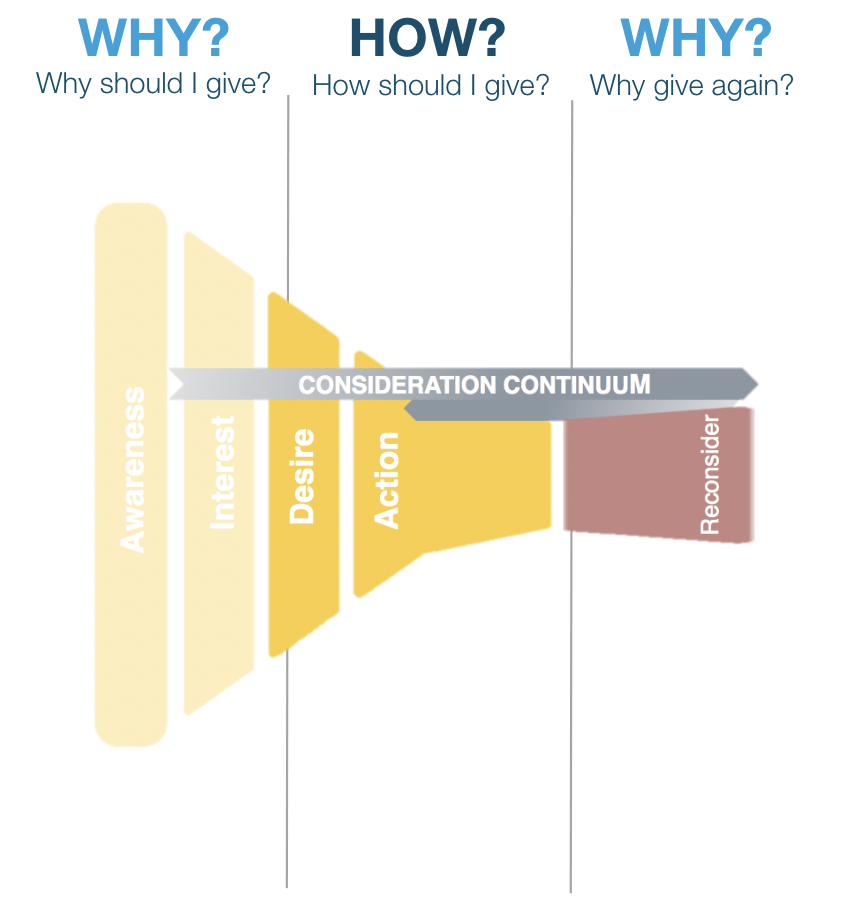

For example, at the right time (when logic arises, at the “How” stage of the consideration continuum—see graphic below), you could supply a menu that includes ways the supporter can overcome the cost barrier by reducing it. For instance, try recommending the supporter take advantage of tax benefits they can gain from changing a standard gift to:

- An asset gift, which lowers capital gains tax

- An estate gift, which occurs after one’s lifetime

- A multi-year pledge, which distributes the cost over time

- A virtual endowment, which funds an ongoing gift over time and/or after one’s lifetime

2. Socializing:

Cost can become social if you “storify” it by making it a friendly character in the fundraising story. Do this by inspiring supporters to find objects to give. This works because objects are social while money is anti-social.

Your job is to help supporters advance their hero story by encouraging them to identify objects (assets) they can give, such as:

- Houses

- Land

- Artwork

- Jewelry

- Businesses

- Shares of any of the above

- Etc.

3. Comparing

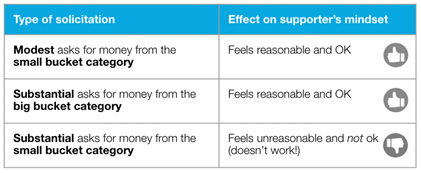

Again, relative to giving cash, giving assets feels less onerous to supporters because asset gifts compare with the entirety of one’s net worth—their “big bucket category” of money. On the other hand, cash gifts compare only to one’s disposable income—their “little bucket category” of money.

More than 97% of household wealth is held in assets, not in cash or checking accounts. Thus, wealth is the “big bucket” and cash is the “small bucket.”

Additionally, it is important that fundraisers avoid asking for gifts from the small bucket because doing so affects the supporter’s mindset as follows:

Giving cash feels like a losing experience because the money comes from the small bucket category. A $1,000 cash gift can feel onerous. Paying with cash creates a visceral loss experience. Losses hurt, and the more painful the cost feels to your supporters, the less they want to give.

But when people sell appreciated assets, they involve themselves in the big bucket category and even experience a ‘windfall gain’ feeling. This kind of excitement has been proven to result in greater giving.

Bottom line: A $1,000 gift of appreciated stock will feel less onerous to a donor than writing a $1,000 check. Focusing donors on gifts of assets moves the reference point for them. It makes the donor feel like the cost is reduced.

4. Subtracting.

Subtraction helps to make the cost of giving feel smaller. This is an important concept because Dr. James’ research found that applying subtraction (lowering the feeling of the cost of giving) increases motivation to give.

In consumer marketing, rebates and premiums lower the cost of purchasing to increase motivation. Rebates and premiums work in fundraising too (ie- free address labels).

But we’re talking about major gifts and legacy gifts here. More address labels won’t do the trick. Instead, what works is making supporters aware of tax benefits (for instance). When they calculate their tax savings they also feel that the cost of giving has been reduced. Then motivation increases. Plus, it becomes more likely that they’ll use the tax savings to make an even bigger gift.

Perks such as raffles and auctions also reduce the cost of giving. But for major gifts we recommend offering perks to build deeper relationships. For example, if you work for a symphony orchestra, why not invite your major donor prospects to a backstage, VIP experience? Perhaps offer a question and answer session with musicians, an opportunity to preferred seating, or a special parking spot (especially if your donor is elderly and can’t walk very far).

CAUTION! Perks work as long as the supporter feels they don’t add cost to the charity. Subjective subtraction usually works better for raising major gifts of assets because it doesn’t bring logical, rational thought into the process. (Objective subtraction does.) However, perks usually require more time and effort on the part of the supporter and the organization.

So why do tax benefits motivate giving and inspire larger gifts?

Although numbers, finance and math involve logical deliberation and the activation of the Stop System’s mechanism in the brain (thereby interrupting social emotion), they also lower the cost barrier for making a gift.

Use words that position the tax benefit in a way that highlights the supporter’s heroism. For instance, tell them they can use a special tool to win a greater victory. This helps to advance the donor’s hero story better than using words that mostly highlight selfishness. For instance:

“Give, and the government will match your gift with a tax reduction.”

“You can give more if you give smarter by allowing the government to fund part of the cost of your gift.”

Or insert perks into the donor’s hero story such as:

- Backstage passes

- Premium seating

- Special parking

- VIP social gatherings

- Insider webinars

- Etc.

These work because they provide social-emotional value while the cost to the organization is minimal at best.

5. Number multiplying and dividing.

A charity might ask two donors for $100 each. However, for each of the two donors, the same charity can multiply the feeling of being generous through an auction. That way, two donors can be part of one gift experience while dividing the cost. Here’s why it works:

- An auction is public and social-emotional.

- A person donating an object for an auction can be known, which enhances their reputation and identity.

- Gifts of objects to be put up for auction can provide a donor greater enhancement to their reputation since their generosity is on display.

- A person donating to receive an object at an auction (the bidder) makes their interest public and social-emotional.

- Bidding on objects is a fun, exciting experience.

- Bidding gives people opportunities to display their wealth, generosity, and commitment to the community.

- All of the above costs the charity nothing!

This doesn’t necessarily mean you should develop more auctions. In some cases, marketing pledges can generate the same result—multiplying and dividing. Pledges involve a two-step process that results in raising more money because they multiply the gift experience into two steps, making the donor feel like a hero twice.

- Step 1: Donor makes a pledge to give a certain amount.

- Step 2: Donor fulfills the pledge and transfers the funds.

Additionally, a pledge divides the cost of giving because a pledge to give later makes the cost feel smaller and less painful than giving now. Experiments resulted in average increases in giving by more than a third—with higher retention rates a year later—when donors were first asked to consider increasing their donations at a future time. This made the donors feel like heroes twice while reducing the feeling of the cost.

Wrapping up.

Make no mistake, wealthy people care a lot about the cost of giving. It’s up to you to help them reduce cost either objectively or subjectively. Do that and you’ll help them feel good about giving. As a result, they’ll give exponentially more.

Just remember it works best when you first listen to their stories and then tell (and help your supporters involve themselves with) stories about how others like them have lowered the cost of their giving while using assets to find meaning in their lives and gain other forms of value.

Related Posts:

- Why wealthy people care about cost even when it comes to philanthropy

- 7 big ideas for raising ‘major gifts of assets’ right now from Dr. Russell James