We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

Why Questions are Important to Advance the Donor’s Hero Story

“It’s very important not to know all the answers. Often we don’t know, and if we did it would be no good, for it is of greater value to the patient when he discovers the answers himself.” -Carl S. Jung[1]

The next set of article postings will be the most practical in the series. And still, we start with theory. This isn’t just a penalty for reading something written by a professor. In the end, it’s quite practical. Yes, we’ll get to lists of tips and tricks. We’ll look at magic phrases and powerful questions. But first, it helps to know what we’re doing. It helps to know who we’re being. Once we get that, everything else fits. It fits the story. It fits the model. It fits the theory.

Delivering value

What does a charity offer that the donor wants? A charity can provide value to many people in many ways. But fundraising provides value to the donor in just one way – by delivering an enhanced identity.

This can be private. It can affirm a donor’s desired moral identity internally. The audience for the gift can be simply the donor himself. The gift can enhance personal meaning.

This can also be public. The gift can project a desired moral or economic identity externally. The audience for the gift can include valued members of the donor’s community. The gift can enhance reputation.

Fundraisers can provide value. They do so as “merchants of meaning” or “retailers of reputation.”

Back to the “one big thing”

The “one big thing” in fundraising is this: Advance the donor’s hero story. Enhanced identity is part of this story. It is the ultimate result.

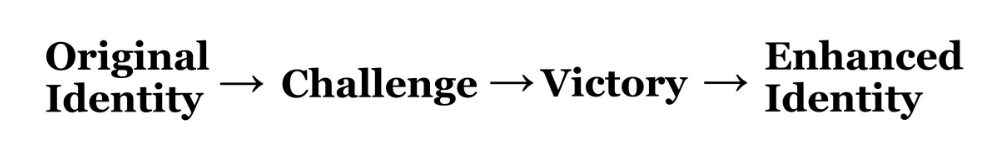

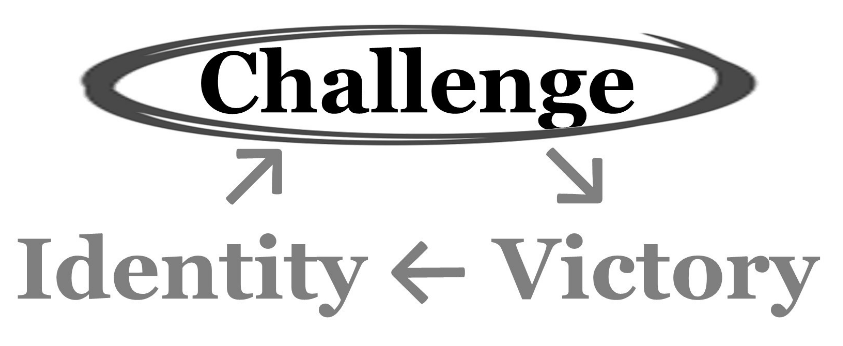

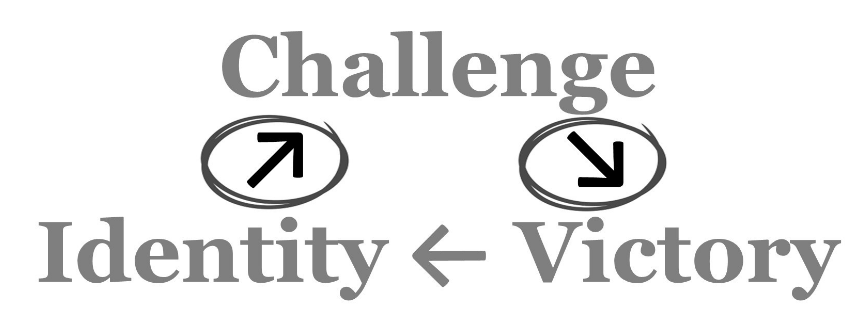

The hero’s journey[2] begins in the hero’s original world. This defines his[3] original identity. He is then challenged to leave behind that ordinary, small, self-focused world. He is challenged to make an impact on the larger world. He initially refuses, but then accepts the challenge. The journey ultimately results in a decisive victory. The hero returns, bringing improvement to his original world. His identity has changed. He has become a transformed (internal) and honored (external) victorious hero.

The steps in the hero’s journey (monomyth) can be simplified to

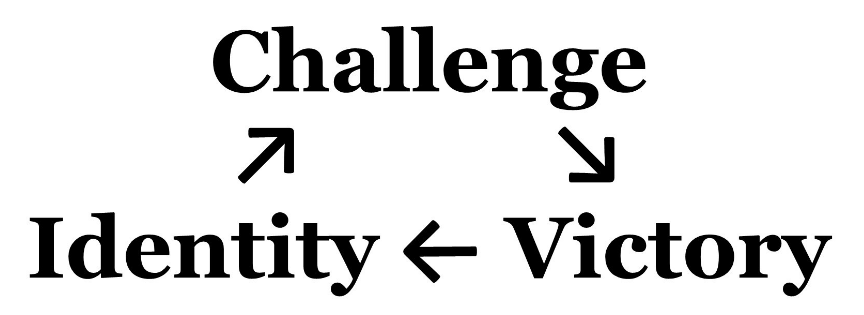

Or as a cycle

A compelling story requires each step. Each part must connect to the others. A challenge isn’t compelling if it doesn’t promise a victory. A victory isn’t meaningful unless it delivers enhanced identity. An enhanced identity requires connecting with original identity.[4] And so on for every step in the cycle. Each step must connect to the others.

The perfect ask

What do new fundraisers really want to know? It’s often something like this.

“How do I ask for money in just the right way?”

“What’s the magic phrase that will make donors give?”

Focusing on the perfect ask is natural. In the monomyth cycle, the ask is the challenge.

- A compelling challenge forces a decision. But it’s a challenge that links to the donor’s identity.

- The challenge responds to a threat or opportunity. But it’s a threat or opportunity for the donor’s people or values.

- The challenge promises a victory. But it’s a victory for the donor’s people or values.

The challenge isn’t compelling by itself. It’s compelling only as part of the full story cycle.

- The challenge looks backward. It connects with the donor’s original identity. It connects with the donor’s history, people, or values.

- The challenge also looks forward. It promises a meaningful victory in the future.

The promised victory is meaningful only as part of the full story cycle.

- The victory looks backward. It benefits the donor’s source of original identity. It helps the donor’s people or values.

- The victory also looks forward. It delivers an enhanced identity to the donor. The donor returns as a victorious and transformed hero.

The perfect ask cannot exist in isolation. The challenge is only a single step. To be compelling, it must be part of the full story cycle. It must advance the donor’s hero story.

Appreciative inquiry

Advancing this story can start by asking and listening. This can uncover the donor’s

- Original identity (related to the charity, cause, or project), and

- Meaningful victory (related to the charity, cause, or project).

Only then can the fundraiser find or create a relevant

- Challenge (related to the charity, cause, or project).

Questions can do a lot. Of course, they can uncover information. But they can do more. Empathetic listening signals a social or friendship relationship,[5] rather than a purely transactional one. This encourages sharing.[6]

Questions can also teach. Even more, questions allow people to teach themselves. Questions can change “an idea” into “my idea.”

Socratic fundraising

In the donor-hero’s journey, the effective fundraiser plays an essential role. The fundraiser is the guiding sage who challenges with a choice. In film, we see this character in Obi-Wan Kenobi, Minerva McGonagall, Morpheus, or Gandalf the Grey.

But the best example of the guiding sage isn’t from film or fiction. The best example is from history. When questions go beyond simply eliciting facts, we enter the world of Socrates.

Socrates taught by asking questions. The purpose of his questions was not for him to learn something. It was for the student to learn something.

Law school

The Socratic method of teaching is familiar to law students. The law professor isn’t asking questions because she wants to learn something. She is asking questions because she wants the student to learn something.

Isn’t it easier just to tell the student the right answer? Yes. It is easier.

But if the student uncovers the answer through his own reasoning, things change. The answer isn’t just the teacher’s opinion. It’s the student’s opinion. He discovers it. He believes it. He understands why he believes it.

As Blaise Pascal wrote in 1660, “People are generally better persuaded by the reasons which they have themselves discovered than by those which have come into the minds of others.”[7]

The wisdom of experience

This isn’t just a matter of ancient history, philosophy, or fiction. It’s a practical tool for transformational philanthropy.[8] As Rod Zeeb puts it, “We ask the questions because what they say is fact; what you say is opinion. If you tell them something, it is just an opinion, even if it is totally accurate. But, if they tell you the same thing, it is a fact. We have to ask them questions so they can tell us the facts.”[9]

Socratic fundraising isn’t new. Successful fundraisers already know this secret. It’s a common theme in fundraising advice. In a summary of dozens of fundraising advice books, Dr. Beth Breeze concludes, “… best practice among successful fundraisers reflects the axiom that: ‘The idea to give must come from the donor. The facilitation of the idea is the responsibility of the [fundraiser]’.”[10]

In describing her most memorable multimillion-dollar gift, fundraiser Pamela Davidson explains, “That is my goal always, to have a gift conversation – which is a far less stressful goal for both a prospect and the professional than a gift … I asked the couple many open-ended and logical questions …”[11]

One study of 1,200 university major gift officers described the special traits of the most successful. It called them “Curious Chameleons.”[12] They were inquisitive and flexible. They asked prospects “thoughtful, insight-generating questions about their goals and interests.”[13]

In studies, stories, theory, and experience, the answer is the same. Appreciative inquiry works. Questions work.

A rose by any other name: Universal fundraising

At its core, the cycle is universal.

But these labels aren’t necessary for it to work. The same concepts arise in many approaches.

One describes fundraising steps as

- Do you care? [i.e., Identity connections]

- How do you want the world to be different? [i.e., Defining a victory]

- Here’s your chance. [i.e., Making the challenge]

Another includes, [14]

- Identify and confirm their interests: “So, it sounds like you care about …?” [i.e., Identity connections]

- What is your goal in your giving? [i.e., Defining a victory]

- Can I come back with a proposal? [i.e., Making the challenge]

The language or sequence may vary, but the elements are there. Successful paths are similar. Questions are a big part of the process. This is true beyond just fundraising.

A rose by any other name: Universal sales

Major gifts fundraising is different from typical sales. But it does have more in common with major transaction sales. Such major contracts are often preceded by years of relationship building.

The classic text on such sales is the 1980s book SPIN Selling.[15] It’s based on 12 years of research and 35,000 sales calls. A summary explains, “To win larger, consultative deals … salespeople must abandon traditional sales techniques. Rather than twisting their customers’ arms, they need to build value, identify needs, and ultimately, serve as a trusted advisor.”[16]

Sound familiar? It should. And not just in its conclusion.

SPIN (S-P-I-N) selling is an acronym of four steps.

- Learn the customer’s Situation.

- Get the customer to identify a Problem.

- Get the customer to elaborate the Implications of the problem.

- Present a product or service that promises a solution. This “Need payoff” addresses needs defined by the customer in the previous steps.

Now compare. Advancing the donor’s hero story with Socratic fundraising means

- Learn the donor’s backstory and original identity related to the charity, cause, or project. (This is the donor’s Situation.)

- Get the donor to define a meaningful victory. (A victory overcomes a Problem – a threat or opportunity.)

- Get the donor to elaborate on the identity connections that make the victory meaningful. (These are Implications.)

- Present a challenge that promises a meaningful victory. A meaningful victory “pays off” in an enhanced identity. (This “Need payoff” enhances identity as defined by the customer in the previous steps.)

The steps match. Advancing the donor’s hero story with Socratic fundraising is SPIN selling. It’s SPIN selling of an enhanced identity. It’s SPIN selling of private meaning or public reputation.

What’s the point? Triangulation. Different people using different methods in different times and places all point to the same answer. When this happens, pay attention to that answer.

Next steps

In the donor’s hero story, the fundraiser is the hero’s guiding sage. For the guiding sage, questions are important. They’re not just a way to discover information. They’re a way to influence the hero’s journey and destination.[17] Jung writes, “Often the old man in fairytales asks questions like who? why? whence? and whither? for the purpose of inducing self-reflection and mobilizing the moral forces …”[18]

For the fundraiser, the real goal is not to tell a story. It’s to guide the donor to tell his own story. It’s to guide the donor to tell his own donor-hero story.

Now what? How can we actually do this? What specific questions do we ask? The next article looks at this.

Footnotes:

[1] Bennet, E. A. (1982). Meetings with Jung. Anchor Press. p. 32.

[2] Joseph Campbell uses a three step circular illustration with this description,

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Campbell, J. (1949/2004). The hero with a thousand faces (commemorative ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 28.

I label these steps as follows:

The beginning point of “the world of common day” is “original identity.”

“Venturing forth into a region of supernatural wonder” is “challenge.”

“Fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won” is “victory.”

“The hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man” is “enhanced identity.”

I apply this both to a scenario where the charitable gift serves only as the final step in the heroic life story and where the gift request itself constitutes the challenge that promises a victory delivering enhanced identity. In a conventional narrative arc, the steps of original identity, challenge, victory, and enhanced identity also serve as backstory, inciting incident, climax, and resolution, respectively.

[3] As a convention for clarity and variety, throughout this series the donor/hero is referred to with “he/him/his” and the fundraiser/sage is referred to with “she/her/hers.” Of course, any role can be played by any gender.

[4] For elaborations of this concept, see e.g., Elenbaas, J. D. (2016). Excavating the mythic mind: Origins, collapse, and reconstruction of personal myth on the journey toward individuation. [Ph.D. Dissertation]. Pacifica Graduate Institute; Gerhold, C. (2011). The hero’s journey through adolescence: A Jungian archetypal analysis of “Harry Potter”. [Ph.D. Dissertation]. The Chicago School of Professional Psychology.

[5] In one experiment with speed daters, “one more question on each date meant that participants persuaded one additional person (over the course of 20 dates) to go out with them again.” Quoted in Brooks, A. W., & John, L. K. (2018). The surprising power of questions. Harvard Business Review, 96(3), 60-67. Citing to Huang, K., Yeomans, M., Brooks, A. W., Minson, J., & Gino, F. (2017). It doesn’t hurt to ask: Question-asking increases liking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(3), 430-452.

[6] See Book I in this series, The Storytelling Fundraiser: The Brain, Behavioral Economics, and Fundraising Story, Chapter 10: Using family words not formal words in fundraising story. See also Book III in this series, The Primal Fundraiser: The Natural Origins of Effective Fundraising, Chapter 4: Relationship is the foundation of primal fundraising: I’m with them because we’re partners!

[7] Pascal, B. (1660; 1910). Pense̕es (trans: Trotter, W. F.). Collier & Sons. p. I.10.

[8] Rod Zeeb at The Heritage Institute defines “transformational philanthropy” as “a gift that means as much to the donor as it does to the organization.” Zeeb, R. (2016). Rod Zeeb talks about transformational philanthropy. [Video]. https://theheritageinstitute.com/speaker

[9] Zeeb, R. (2011). Multi-generational planning. (pp. 347-353). Annual meeting proceedings of the million-dollar round table. p. 352. http://www.imdrt.org/mentoring/2011_Zeeb.pdf

[10] Breeze, B. (2017). The new fundraisers. Policy Press. p. 149. Quoting from Matheny, R. E. (1995). Communication in cultivation and solicitation of major gift donors. In New directions in philanthropic fundraising, 10 (pp. 33-44). p. 43.

[11] Davidson, P. (2019). Pamela Davidson. In E. Thompson, J. Hays, & C. Slamar (Eds.), Message from the masters: Our best donor stories that made a difference (pp. 49-63). Createspace Independent Publishing. p. 55.

[12] O’Neil, M. (2014, September 24). ‘Curious chameleons’ make the best major-gift officers, new study says. The Chronicle of Philanthropy. https://www.philanthropy.com/article/Curious-Chameleons-Make/152575

Education Advancement Board. (2014). Inside the mind of a curious chameleon. https://eab.com/insights/infographic/advancement/inside-the-mind-of-a-curious-chameleon/

[13] Id.

[14] Birkholz, J. M., (2018, September 17). Identifying major gift donors. [Presentation]. Practical Planned Giving Conference, Orlando, Fl.

[15] Rackham, N., Kalomeer, R., & Rapkin, D. (1988). SPIN selling. McGraw-Hill.

[16] Frost, A. (2018). SPIN selling: The ultimate guide. [Website]. https://blog.hubspot.com/sales/spin-selling-the-ultimate-guide

[17] “These cause the who? where? how? why? to emerge clearly and in this wise bring knowledge of the immediate situation as well as of the goal. The resultant enlightenment and untying of the fatal tangle often has something positively magical about it …” Jung, C. G. (2015). Aspects of the masculine (3rd ed.). Routledge. p. 405.

[18] Read, H., Fordham, M. & Adler, G. (Eds.). (1953-1978). The collected works of C. G. Jung (20 vols). Routledge, 1953-78. Vol. 9, Part 1, paragraph 404. Note that the “guiding sage” archetypal monomyth character referenced in this series is, in Jung’s work, called the wise old man. In the same paragraph he explains, “The old man always appears when the hero is in a hopeless and desperate situation from which only profound reflection or a lucky idea, in other words, a spiritual function or an endopsychic automatism of some kind can extricate him. But since, for internal and external reasons, the hero cannot accomplish this himself, the knowledge needed to compensate the deficiency comes in the form of a personified thought, i.e., in the shape of this sagacious and helpful old man.”

Related Resources:

- Donor Story: Epic Fundraising eCourse

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- The Zoology of Fundraising: More Chameleons, Fewer Peacocks

- How to develop a ‘character’ in your fundraising stories in 3 steps — according to Dr. Russell James

LIKE THIS BLOG POST? SHARE IT AND/OR LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!