We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

Why answering “no” to these four questions guarantees failure in your fundraising efforts

The right metrics

Fundraising metrics can’t do everything. But they can answer four key questions:[1]

- Are we focused on the right donors?

- Do we have individual plans for them?

- Are we seeing them?

- Are we asking them?

These are important questions. Answering “yes” doesn’t guarantee success. But, answering “no” usually guarantees failure. This is also a common feature of metrics in storytelling.

Suppose we were managing novel writers. One metric might be hours per day spent writing. Another might be words per day. Hitting these metrics won’t guarantee a successful novel. But their absence does guarantee failure.

The best metrics encourage activity. But not just any activity. The best metrics encourage doing the hard stuff.[3] We don’t need encouragement to do the fun parts. So, let’s look at some hard stuff when it comes to fundraising.

1. Are we focused on the right donors?

Fundraising math v. fundraising emotion

So, let’s start with the hard stuff. There’s a difference between what’s fun and what’s important. Consider some simple math.

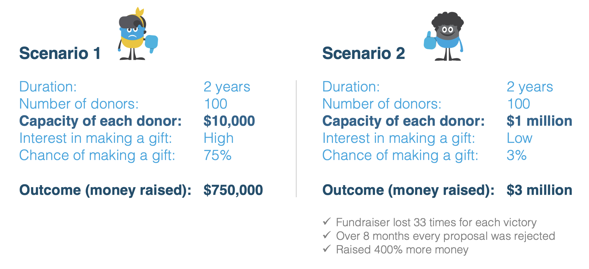

Scenario 1. You spend the next two years working with 100 donors. Each has capacity to make a $10,000 gift. Interest in giving is high. Each has a 75% chance of making that gift.

Scenario 2. You spend the next two years working with 100 donors. Each has capacity to make a $1 million gift. Interest in giving is low. Each has a 3% chance of making that gift.

Mathematically, the answer is easy. Scenario 2 raises four times as much money. The charity receives $3,000,000 instead of $750,000.

Emotionally, the answer is hard. Suppose you make one gift proposal per week. That’s 100 over the course of two years. In Scenario 1 you constantly win. Three out of four weeks, you bring back a big gift.

In Scenario 2, you constantly lose. On average you’ll lose 33 times for every victory. You’ll have all of your proposals rejected for over 8 months. And you’ll raise four times as much money.[4] What feels like losing actually wins. Emotionally, a series of small wins feels more attractive. But that’s not how the numbers work.

Sports math v. sports emotion

The same result happens in modern sports. Before analytics, coaches and players did what “felt” good. They avoided the negative emotions of any negative outcome. After analytics, games changed. Higher risk, higher reward tactics grew. In basketball, the three-point shot took over. This shot also has the greatest chance of missing. Baseball moved to home runs or bust. This also increases strike outs. In football, throwing increased over running. This also has a higher risk of a turnover or no gain.[5]

In each case, analytics corrects the emotions of “loss aversion.” It moves towards higher risk, higher reward tactics. In both sports and fundraising, the emotions don’t match the math. Focusing on winning a larger share of plays (or asks) feels better. Focusing on winning the biggest plays (or asks) actually works better.

Major donor math

Ideally, we want donors with high interest and high capacity. But capacity and interest are not equally important. That’s not how the math works. That’s also not how people work.

We can influence a donor’s interest. Creating donor experiences helps. Building relationships with the charity employees, beneficiaries, or other donors helps. Making connections with the donor’s values, people, and life story helps. Any of these can change interest. And what can we do to change a donor’s capacity? Nothing.

The right behavior requires spending time with high-capacity prospects. But the right behavior isn’t the easy behavior. As James Daniel writes, “Many would gladly trade cold million-dollar prospects for warm ten-thousand-dollar prospects. Unfortunately, many do make this swap – a recipe for failure.”[6]

The prospect prescription

The right metrics should nudge the right behavior. The right behavior requires spending time with high-capacity donors. There are, of course, many ways to measure this. We might have capacity minimums for major gift officer portfolios. We might multiply activity metrics by capacity rating. (Getting a visit with a high-capacity prospect is a bigger deal.) We can be more flexible with high-capacity success rates and timetables.

But what if we don’t have enough high-capacity donors? What if we don’t have any? Systematic, planned efforts to contact new prospects can help.[7] John Greenhoe relates, “the most successful development officers I have worked with developed a regimented procedure for connecting with new prospects.”

Referrals can work, too. We can always ask, “Who do you know that may be interested in our work?” [8]

But what works better is to start with what we can give, not what we want to get. This starts with a simple question: “How can we provide value to high-capacity prospects?”

Maybe we’re offering attractive experiences. Maybe we’re giving recognition or prestige. Maybe we’re sharing gift planning expertise. Maybe it’s access to a valuable social network. Our efforts are more likely to pay off when we lead with value.

Internal support: The advocacy story

High-capacity outreach works. Leading with value works. But these take time. Sustaining internal support can be challenging.

It may help to reframe the internal story about prospect outreach. For example, many charities focus on advocacy. But what is advocacy? It’s promoting the cause to those with the power to make a difference.

Getting a 30-minute meeting with a senator is reason for celebration. Why? Because that person has capacity to make an impact for the cause. What about getting a meeting with a high-capacity prospect? This should also be a cause for celebration. Why? Same reason.

Advocacy is celebrated. It’s part of the core mission. Expanding the advocacy story to include major donor discovery can change perspectives. It can increase internal support for these long-term processes.

Do we have the right legacy prospects?

With legacy giving, the hard stuff gets even harder. Wealth is important in giving. It’s even more important in legacy giving. In annual giving, a low-wealth donor can make substantial contributions. In legacy giving, he can’t. In annual giving, the value of small gifts can accumulate over many years. In legacy giving, there’s only one gift. The wealthiest 0.1% of decedents donate 59% of all charitable estate dollars.[9] Also, wealthy people give a larger share of their overall donations as legacy gifts.[10]

And it gets harder. Old-age and end-of-life decisions dominate. Nearly 80% of charitable estate dollars are transferred by documents signed by donors in their 80s, 90s, or older.[11] Most charitable decedents switched from non-charitable estate plans in the final 5 years of life.[12]

Charities also get dropped from plans. Among older adults, the ten-year retention rate for a charitable estate component is only 55%.[13] Only 65% of legacy society members actually generate estate gifts.[14] Part of the reason is this: About 1 in 4 legacy society members received no communications from the charity in their last two years of life.[15] Why? Often, it’s because charities communicate based only on recency of donations. Charitable decedents normally stop donating during the last few years of life.[16]

Who are the right legacy prospects? The oldest, wealthiest, childless friends of the charity.[17] The money will come from just a few, extreme donors. In financial terms, typical donors don’t matter. For example, most estate donors leave less than 10% of their estate to charity. Taken together, these typical donors transfer only 3.8% of total charitable bequest dollars.[18] Most money comes from the tiny fraction of donors that give 90% or more of their estate to charity.[19]

Given all this, common legacy metrics are simply wrong. This is a world dominated by statistical extremes. Only the outliers matter. Yet, charities typically count every donor as “one.” A ten-million-dollar planned estate gift from a childless, 95-year-old? That’s one. That’s one legacy society member. A 25-year-old adding the charity as a death beneficiary on a new bank account? That’s also one. One legacy society member.

And it gets worse. Getting a new legacy society member only starts a process that might eventually lead to money. These are, after all, highly fluid decisions, especially near the end of life.[20] But fundraisers are rewarded only for starting this process. They get no reward for continuing it.

And it gets even worse. Generating a new legacy plan counts as one. This may require months of working with a donor. Discovering a pre-existing plan counts the same. This requires a postage stamp on a mass survey.

The legacy prospect prescription

Legacy metrics could be different. They could separate plan discovery from plan creation. They could also value gifts differently.

Valuing an irrevocable estate gift is simple.[21] One from a 55-year-old donor counts at 33% of face value (using a 5% interest rate).[22] Multiplying again accounts for the risk of revocation: 33% of 33% is 11%. This revocable gift counts at 11% of face value.

This approach can also reward maintaining relationships. Reconfirming the gift at 65 adds another 10% of face value. (At this age, 46% of 46% is 21%.) Reconfirming again at 72, 77, 82, 87, and 92 adds 10% of face value each time.[23] This creates ongoing goals. It avoids a “count it and forget it” approach.

Of course, counting new plans as “one and done” is easier. It makes life more fun. Fundraisers can just spend time with donors their own age. They don’t have to worry about maintaining relationships until the end of life. They don’t have to deal with “old people” attitudes, frailties, and family. They also don’t need to worry about wealth or complex plans. A token gift counts the same as a massive one.

Are the right metrics the answer in legacy giving? They can help, but other factors also matter. A charity’s cause or culture matters. Some causes win because they’re naturally in front of people in their 80s and 90s. Pets, cancer, healthcare, and hospice are normally winners.[24]

Others succeed with a culture that values visiting their oldest friends. (They may be especially concerned for those who have no children visiting them.) This works for legacy fundraising.[25] Many universities never lose contact with their alumni – regardless of their current donations.[26] This also works for legacy fundraising. Others include legacy giving as part of their regular messaging. Again, this works for legacy fundraising.

These charities may not “measure” any better. They may not measure at all. But doing the right things still works, even without the metrics. Metrics can help. But the charity’s cause and culture matter more.

2. Do we have individual plans for them?

Individual plans: Research findings

The business world doesn’t have “major donors.” It doesn’t have “principal gifts.” Instead, it has “key accounts.” What works in the world of key account management? One study looked at 20 practices across 209 businesses. It then statistically tested to see which predicted success. The answer? Only one practice simultaneously predicted

- Increased share of customer spend

- Revenues

- Customer satisfaction

- Relationship improvement, andImproved retention.[27]

What was it? Having individual plans for each key account. The winners planned each account separately to ensure the best service. This finding is powerful, but it’s not new. Many studies have found similar results.[28] Individual plans are key for key account management.

This also works in fundraising. A nationwide study of the most effective major gifts fundraising metrics found this: “Written strategies for each gift officer’s top 25 to 50 prospects with specific initiatives, specific persons to be involved in each task including internal partners and external volunteers, and specific target dates for each purposeful action should be required and documented …”[29]

Individual plans: Why do they work?

Why are individual plans so powerful? First, consider the business answer. The successful business is a valued advisor for its key customers. This consultative relationship requires individual plans.

This is different than just selling. Selling doesn’t need individual plans. Selling just pushes the product. The customer’s path is always the same: buy! Then buy some more! In key account management, individual plans are essential. In traditional sales, they don’t matter. Thus, this one factor divides the two approaches.

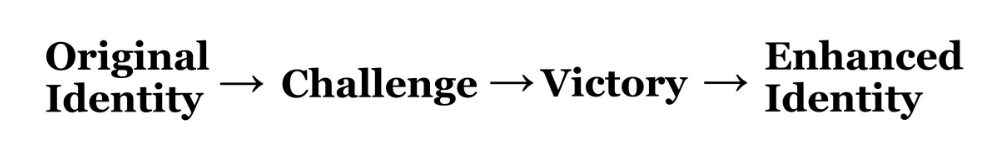

Next, consider the fundraising answer. The “one big thing” in fundraising is always the same: Advance the donor’s hero story. Will that story be the same for every donor? Of course not. If it is, then it’s not the donor’s story. An individual story requires an individual plan.

An individual plan can help to advance the donor’s story. It can map out a journey with specific steps. A step might link to the donor’s identity: his people, values, or life story. It might connect these to the charity, the cause, or a specific challenge. It might show how a gift has led to a victory. It might confirm the personal meaningfulness of that victory.

Not every meeting will include an ask for a gift. But every meeting should include an ask. The ask is for the next step in the donor’s plan. This might be to take a tour. It might be to attend a meeting. It might be to listen to a proposal. The donor’s individual plan guides the process. This plan can change just “seeing them” into advancing the donor’s journey.

Of course, having individual plans won’t guarantee success. But not having them probably shows that something is missing. If individual plans feel unnecessary, watch out!

- You might just be “pushing product.” This is different than being the donor-hero’s “guiding sage.”

- You might not have the right donors. Only high-capacity donors warrant individual plans.

- You might just be acting friendly instead of fundraising. Just talking doesn’t progress towards a meaningful ask.

3. Are we seeing them?

An important start

It’s hard to raise major gifts sitting in the office. “Go see people,” helps. Seeing the right people helps more. Seeing the right people as part of a personal customized plan helps even more. These don’t guarantee success, but not doing them probably does guarantee failure. It’s like writing a novel. Hitting 2,000 words per day doesn’t guarantee success. But hitting 0 does guarantee failure.

How do we answer, “Are we seeing them?” First, “them” means the high-capacity donors from step 1. Second, “seeing them” is not just about the number of visits. It’s also about the share of the portfolio visited.[30] You might have 1,000 personal visits. But for a donor you didn’t visit, the answer to this question is still, “No.”

This highlights another problem. Why do we have so many people in the portfolio? The answer is often bad metrics. As one author explains, “If the primary goal is total funds raised … it is in an officer’s best interest to have a very large portfolio of already proven donors.”[31]

As a result, “Portfolios tend to grow into unwieldy hordes of neglected names or become stagnant like ponds disconnected from moving water.”[32]

Having too many people in the portfolio can be a problem. It’s a problem when it changes the answer to the question, “Are we seeing them?”

What do we do when the answer to this question is, “No.”? How can we fix it? There are two answers:

- Reduce (or divide) the portfolio.

- See more people.

Let’s look at each option.

“Seeing them” solutions: Reduce the portfolio

Major gift officers often have 125-150 donors in their portfolio. This is at or beyond the extreme maximum for maintaining human relations.[33] Managing that many relationships can lead to minimal contacts with each person.

Often, focusing more time on the best prospects works better. One way to do this is to make the portfolio smaller. Don’t be afraid. This isn’t the end of the world! One report finds, “Institutions that have reduced Major Gift Officer portfolio size have actually seen increases in the number of asks, number of gifts, and overall dollars raised.”[34]

An analysis of hundreds of campaigns found, “In the vast majority of cases, portfolio optimization provides the biggest delta in rapid production increases … It is a simple question of, “Are we seeing the best prospects?” So much energy goes into the “seeing,” but the “best prospects” portion of the question continues to be our main missed opportunity pain point.”[35]

“Seeing them” solutions: Divide the portfolio

If a smaller portfolio isn’t acceptable, another approach can work. Separate the portfolio into active and passive relationships. In active relationships, the donor is in cultivation for a gift. The individual plan is moving toward a time-targeted ask. The fundraiser must be visiting, or at least regularly seeking visits, with all active group participants.

In contrast, the passive portfolio has fewer – or no – visit expectations. The donor gets special attention only if the donor initiates contact. The fundraiser is still available when needed. Responding to donor requests is still important. Taking advantage of chance encounters is great. Receiving unexpected gifts is wonderful. But these aren’t the same as planned activities. And they shouldn’t be counted the same.

Actively dividing a portfolio is different than passively ignoring part of it. Dividing is planned. It’s based on interest, capacity, and the individual donor journey. Ignoring is reactive. It encourages the easy meetings, not the important ones.

“Seeing them” solutions: See more people

The question is, “Are we seeing them?” We want to answer, “Yes.” One approach is to reduce the number of people who count as “them.” The “them” is limited to key high-capacity donors.

Another approach is to see more of these people. How? More effective strategies for setting appointments can help. So can nudging fundraisers to prioritize visits. But usually, it is the manager’s behavior that drives this number.

What prevents fundraisers from hitting their visit goals? A study of 660 frontline fundraisers found the answer.[36] Managers started with high goals. They wanted fundraisers to spend most of their time on major gifts fundraising. But few met these expectations. Why not? The fundraisers identified the barriers:

- 70% referenced other administrative work.

- 52% referenced team and program management.

- 46% referenced events.

- 43% referenced support to deans/units/programs.

Another study found a similar result. One manager of a high-growth-fundraising charity explained it this way, “You would think I maintained tight oversight of my team, but in reality, I spend most of my time managing the organization so that my team can maximize their impact.”[37]

With competent and willing fundraisers, the biggest change will come from the manager’s behavior. The manager’s task is to protect the fundraiser from the endless array of low-value, internal, “urgent” tasks.[38] The manager frees the fundraiser to “Go see them.”

4. Are we asking them?

Making the hero story ask

Asking doesn’t guarantee success. But not asking probably does guarantee failure. Asking metrics are important because asking is hard. Metrics help focus actions on the hard parts.

Asking is important. Making the right ask is even more important. The right ask will advance the donor’s hero story. Every hero story has a “call to adventure.” It is a challenge. It will link,

This rarely happens with a generic, shotgun-style approach to asking. It requires a planned, personal ask.

Advancing a hero story requires a heroic “call to adventure.” A small, comfortable ask cannot fill this role. The heroic ask is “big.” It can be big relative to past giving. It can be big relative to other capacity measurements.

One study analyzed nearly 1,000 gift officers. The top 20% highest-producing fundraisers raised about 75% of the dollars. What was different about these special fundraisers? Two of the factors related to asking. The study found, “The top 20 percent of officers tended to solicit gifts at the research capacity ratings … The bottom 80 percent tended to ask for about 40 percent of the capacity ratings …”[39]

There was also another difference. This heroic ask was a planned step in a journey. It was part of a specific, defined process. The study explained, “Top performers have a consistent timeframe for managing the cultivation process, and the average was about 11 months. Lower performers either asked too soon for lesser levels,or dragged out the process. It is best to have a consistent action path that leads toward solicitation.”[40]

Other research finds, “Stronger fundraisers go on more calls, yes, but they also ask earlier and make more ambitious solicitations.”[41]

Asking indicators

The right behavior is to make planned, personal, “stretch” asks. Doing this works. But it’s also hard. Asking for the small, comfortable gift is easier. Asking blindly without cultivation is also easier. Putting off the ask, or avoiding it altogether, is the easiest.

Metrics can help. Too much time in cultivation can be a warning light. It can alert that the donor’s story isn’t advancing.[42] Measuring asks relative to a capacity indicator can help. It can show if the ask is truly a heroic “call to adventure.”

Asking for assets is also powerful. It can change a gift’s reference point from disposable income to wealth. This makes larger gifts feel more affordable. It also allows for broader conversations. These can cover the donor’s wealth and philanthropic goals. It can lead to deeper, consultative relationships. Giving special credit for asset asks can help long-term fundraising growth.[43]

Tracking gifts closed is fine. But beware! Asking to capacity won’t have the same close rate as asking small. A heroic “call to adventure” is often met with an initial, “No.” But a “no,” handled well, can still advance the story. It can show what is, and what isn’t, important to the donor. It can lead to the next challenge.

Team asking

It’s easy to think of fundraising in one-to-one terms. A single fundraiser guides the donor. But it can also be a team effort. Different people can focus on different steps in the story. This can be more effective for several reasons.

Advancing different parts of the donor’s story uses different skills. Reporting impact requires different skills than asking. So does delivering publicity or gratitude. So does building identity connections with the charity.

These different skills can be a more natural fit for different people. They also have different wage costs. It’s relatively easy to find people to manage donor events. It’s much harder to find those who will effectively ask for money. Separating the tasks allows those with high-value skills to spend more time using them.

Also, this division of labor helps people improve. It’s hard to get better at a task when we don’t do it that often. If asking is a rare experience, improvements may come slowly or not at all.

Separating these tasks also prevents story steps from being forgotten. It’s easy to put off making the ask when there are other things to do. It’s easy to skip impact reporting, gratitude, or publicity when there are more urgent tasks. But when a task is a person’s primary focus, it’s unlikely to be forgotten.

Conclusion

So, what’s the magical metric system that guarantees success? Sorry. Metrics probably aren’t “the” answer. In fact, they’re just as likely to be the problem. Metrics aren’t people. They aren’t leadership, strategy, or skills.

A fundraising problem likely isn’t just a metrics problem. Often, it’s a story problem.

- Maybe fundraisers are telling the wrong story. (The administrator-hero story works only for small gifts. The donor-hero story works for large gifts.)

- Maybe fundraisers are being the wrong story character. (The friendly “jester” character may be fun. But advancing the donor’s long-term journey requires the wise and persistent “guiding sage.”)

- Maybe donors lack the capacity to play the major gift donor-hero role. (The major gift “weapon” may be too heavy for this prospective hero to lift.)

But metrics can still help. They can answer:

- Are we focused on the right donors?

- Do we have individual plans for them?

- Are we seeing them?

- Are we asking them?

Having these doesn’t guarantee success. But not having them probably does guarantee failure.

Metrics aren’t magic. They can’t tell the story for us. But they can nudge the right storytelling behavior, especially the hard stuff. They can be a diagnostic “check-engine” light when story parts are missing. They can help, a little, with the “one big thing” in fundraising. They can help advance the donor’s hero story.

Footnotes:

[1] See examples of similar ideas in Wilson, K. L. (2015). Determining the critical elements of evaluation for university advancement staff: Quantifiable and nonquantifiable variables associated with fundraising success. [Dissertation]. East Tennessee State University. (“a) do you have enough prospects, b) are you seeing them, c) are you asking them.” p. 57; “number of personal visits made with rated, assigned prospects as reported in contact reports, and the number of proposals submitted with proposal date, content and asks amount.” p. 58).

[3] The same phenomenon can be seen in sports. One study looked at which activities separated local-level and national-level under-18 soccer players. The national-level players had accumulated more hours in focused practice. They actually accumulated fewer hours in “playful activities” in soccer. It wasn’t just about putting in the hours. It was about putting in the hours doing the hard stuff. Ward, P., Hodges, N. J., Starkes, J. L., & Williams, M. A. (2007). The road to excellence: Deliberate practice and the development of expertise. High Ability Studies, 18(2), 119-153.

[4] In reality, this difference becomes even larger. In the following year, you would have only 3 long-term relationships to manage instead of 75. And the high-capacity donor is more likely to refer to other high-capacity donors, leading to even greater growth differences.

[5] Part of this change can also be attributed to other rule changes favoring the forward pass. Thus, a cleaner comparison would be the increasing propensity to avoid punting on 4th down. Again, analytics more often points to taking the high risk, high reward approach: Go for it on 4th down. Emotions and loss aversion favor the low risk, low reward decision: Punt on 4th down. See Dalen, P. (2013, November 15). Conventional wisdom be damned: The math behind Pulaski Academy’s offense. https://www.footballstudyhall.com/2013/11/15/5105958/fourth-down-pulaski-academy-kevin-kelley

[6] Daniel, J. P. (2009, January 26). Cold calls, the first hurdle. [Website]. BWF. https://www.bwf.com/cold-calls-first-hurdle/

[7] “Fundraisers who are disciplined about calling new prospective donors typically fare well. Those who aren’t usually don’t last long in this field.” Greenhoe, John. (2013). Opening the door to major gifts: Mastering the discovery call. CharityChannel Press. p. 27.

[8] Pittman-Schulz, K. (2012, October). In the door and then what? [Paper presentation]. National Conference on Philanthropic Planning, New Orleans, LA. p. 14. (“Who do you know that may be interested in our work? Would you send a note to introduce me, or arrange for us to do lunch? You like to entertain—how about a dinner party or reception?”); See also Baker, B., Bullock, K., Gifford, G. L., Grow, P., Jacobwith, L. L., Pitman, M. A., Truhlar, S., & Rees, S. (2013). The essential fundraising handbook for small nonprofits. The Nonprofit Academy. p. 154. (“Do you know other people that may be interested in learning about what we’re doing?”).

[9] “in 2017, when only 2,902 estates with charitable transfers filed estate tax returns, these estates still produced the majority (59%) of all bequest dollars transferred to charity in the country.” James, R. N., III. (2020). American charitable bequest transfers across the centuries: Empirical findings and implications for policy and practice. Estate Planning & Community Property Law Journal, 12, 235-285. p. 250. Also see a total of 2,813,503 decedents in 2017 at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db328-h.pdf

[10] Steuerle, C. E., Bourne, J., Ovalle, J., Raub, B., Newcomb, J., & Steele, E. (2018). Patterns of giving by the wealthy. Urban Institute. Table 4. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/99018/patterns_of_giving_by_the_wealthy_2.pdf

[11] James, R. N., III., & Baker, C. (2015). The timing of final charitable bequest decisions. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 20(3), 277-283.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Wishart, R., & James, R. N., III. (2021). The final outcome of charitable bequest gift intentions: Findings and implications for legacy fundraising. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, e1703.

[15] Wishart, R., & James, R. N., III. (2021). The final outcome of charitable bequest gift intentions: Findings and implications for legacy fundraising. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, e1703.

[16] James, R. N., III. (2020). The emerging potential of longitudinal empirical research in estate planning: Examples from charitable bequests. UC Davis Law Review, 53, 2397-2431

[17] James, R. N., III. (2009). Health, wealth, and charitable estate planning: A longitudinal examination of testamentary charitable giving plans. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(6), 1026-1043.

[18] James, R. N., III. (2020). American charitable bequest transfers across the centuries: Empirical findings and implications for policy and practice. Estate Planning & Community Property Law Journal, 12, 235-285.

[19] Id.

[20] James, R. N., III. (2020). The emerging potential of longitudinal empirical research in estate planning: Examples from charitable bequests. UC Davis Law Review, 53, 2397-2431

[21] Valuation Table S for single life and R for joint lives are at https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/actuarial-tables

Simply scroll down to your preferred interest rate and use the “Remainder” percentage next to the age of the donor(s).

[22] Using a 5% interest rate, Table S reports a Remainder value of 0.33032 at https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/actuarial-tables

[23] Of course, this counting is only for internal administrative purposes. It should never be shared with donors. Instead, donors should always receive recognition for 100% of the face amount of any planned gifts.

[24] These causes are typical for charities receiving the largest share of their fundraising income from legacy gifts. See, Pharoah, C. (2010). Charity market monitor 2010. CaritasData.

[25] James, R. N., III. (2020). American charitable bequest transfers across the centuries: Empirical findings and implications for policy and practice. Estate Planning and Community Property Law Journal, 12, 235-285

[26] James, R. N., III. (2020). The emerging potential of longitudinal empirical research in estate planning: Examples from charitable bequests. UC Davis Law Review, 53, 2397-2431.

[27] Davies, I. A., & Ryals, L. J. (2014). The effectiveness of key account management practices. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(7), 1182-1194. Table 8A and 8B. (This was the only factor significantly and positively related to every one of these outcomes.)

[28] McDonald, M., Rogers, B., & Woodburn, D. (2000). Key customers: How to manage them profitably. Butterworth-Heinemann; Ojasalo, J. (2002). Key account management in information-intensive services. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 9(5), 269-276; Ryals, L. J., & Rogers, B. (2007). Key account planning: Benefits, barriers and best practice. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 15(2&3), 209-222; Storbacka, K. (2012). Strategic account management programs: Alignment of design elements and management practices. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 27(4), 259-274.

[29] Grabau, T. W. (2010, July). Major gift metrics that matter. Bentz, Whaley, Flessner. https://www.bwf.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2014/04/00090978.pdf

[30] Megli, C. D., Barber, A. P. & Hunte, J. L. (2014, December). Optimizing fundraiser performance. Bentz, Whaley, Flessner. http://www.bwf.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2015/01/December2014.pdf

[31] BWF Research. (2016, June 23). How to survive drowning in an unwieldy portfolio hoard. [Website]. BWF. https://www.bwf.com/data-science/survive-drowning-unwieldy-portfolio-hoard/

[32] Id.

[33] See an evolutionary argument for a maximum of 150 people in Dunbar, R. I. (2018). The anatomy of friendship. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(1), 32-51. Note that this maximum would NOT suggest a portfolio of this size unless the fundraiser had no other social connections in her life. Another view holds that the number may be about double this for online relationships. See Zhao, J., Wu, J., Liu, G., Tao, D., Xu, K., & Liu, C. (2014). Being rational or aggressive? A revisit to Dunbar׳s number in online social networks. Neurocomputing, 142, 343-353.

[34] EAB. (n.d.). What are the right metrics to measure major gift officer performance? [Website]. https://eab.com/insights/expert-insight/advancement/what-are-the-right-metrics-to-measure-mgo-performance/

[35] BWF Research. (2016, June 23). How to survive drowning in an unwieldy portfolio hoard. [Website]. BWF. https://www.bwf.com/data-science/survive-drowning-unwieldy-portfolio-hoard/

[36] Megli, C. D., Barber, A. P. & Hunte, J. L. (2014, December). Optimizing fundraiser performance. Bentz, Whaley, Flessner. http://www.bwf.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2015/01/December2014.pdf

[37] Sargeant, A., & Shang, J. (2016). Outstanding fundraising practice: How do nonprofits substantively increase their income? International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 21(1), 43-56.

[38] “What could be easier than focusing on the few who can make major gifts and seeing them? Yet, not seeing donors is the most significant and common barrier to success. What’s going on? Most major gift fundraisers have other duties—special events, reports, meetings—that appear more “urgent” than making visits. Visits are urgent only when scheduled; until then, they are movable. Fundraisers fall victim to the tyranny of the urgent and lose focus.” Daniel, J. P. (2009, January 26). Cold calls, the first hurdle. BWF. https://www.bwf.com/published-by-bwf/cold-calls-the-first-hurdle/

[39] Birkholz, J. M. (2018, January). Planned giving fundraiser metrics. Planned Giving Today, p. 6-8. p. 7

[40] Id.

[41] BWF. (2014, July 25). Client advisory – 5 tips for effective, meaningful performance reviews. [Website]. https://www.bwf.com/published-by-bwf/client-advisory-5-tips-for-effective-meaningful-performance-reviews/

[42] “Most programs have a gift officer who has a portfolio filled with prospects in a state of perpetual cultivation that never get solicited…. The time in cultivation metric would serve as a red flag of inaction and a barometer of the efficiency with which prospects move from discovery through cultivation to the actual solicitation.” Grabau, T. W. (2010, July). Major gift metrics that matter. https://www.bwf.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2014/04/00090978.pdf

[43] See James, R. N., III. (2018). Cash is not king for fund‐raising: Gifts of noncash assets predict current and future contributions growth. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 29(2), 159-179.

Related Resources:

- Donor Story: Epic Fundraising eCourse

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- The Next-Gen Major Gifts Fundraising Metrics Your Nonprofit Should Be Measuring

- Stories are more important than metrics

LIKE THIS BLOG POST? SHARE IT AND/OR LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!