Reframing the hero story

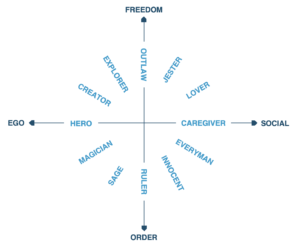

The Hero is a high-ego character. It is at one extreme of the ego-social axis. For those at the opposite end, the character may not fit. It may not feel comfortable. For them, advancing the donor-hero story requires first reframing it. This is achievable. The hero story can be made acceptable for a low-ego, high-social orientation.

The Hero is in the spotlight. He is often a public figure. He is observed and praised by others. For those on the ego side of the ego-social axis, this is great.[1] Such public recognition is welcome.

What about those at the extreme pole away from ego? They may resist individual notoriety. For them, the other philanthropic archetype is easier. The quiet, hidden Caregiver is safer.

But this story encourages small, dispersed giving. Only the Hero archetype matches large, focused, transformational gifts. But how can the Hero’s public recognition be made acceptable? Let’s look at three strategies.

Reframing: The heroic community

The Everyman-Caregiver resists personal fame. The Everyman fears standing out or seeming to put on airs,[2] but he embraces the virtues of the community. Thus, the community of donors can be heroic. The donor community may be praised, recognized, and honored.

This community is part of the donor’s identity. It’s part of the donor’s self. And it’s heroic. So, this is still the donor’s hero story. But the heroism is reframed. It feels less egoistic. It feels more social. It matches the donor’s orientation.

This is still a hero story. It’s still a hero story about the donor. But the donor is not portrayed as separately heroic. The donor is part of a community of heroic supporters.

Reframing: The heroic loved one

The Lover-Caregiver resists personal fame but can embrace honor for a loved one. The donor may not want a building or scholarship fund named for him. That’s egotistical. But naming it after a family member is different.[3] This gives honor to another person. That’s less egotistical.[4]

Nevertheless, the person being honored is part of the donor’s identity. The loved one is part of the donor’s story. They may even share a family name. So, this is still the donor’s hero story. This part of the donor’s identity, or self, is being honored. But because the heroism is first reframed, it fits. It feels less egoistic. It feels more social. It matches the donor’s orientation.

This fits a memorial or tribute gift. This can also work when naming for the “_____ family.” The donor is honored, but only as part of a group of loved ones. Group recognition fits the Everyman-Caregiver. Family or “loved one” recognition fits the Lover-Caregiver.

Reframing: The heroic sacrifice

But what if we want to personally recognize just the donor? Caregiver donors will naturally resist. But even this can be reframed. For example, “I know you aren’t wanting recognition. But if we could share your story in this way, it would set a powerful example. I know it makes you uncomfortable. But allowing us to do this would be like a second gift to [the charity]. It could really inspire others to give. It could make a big difference.”

The recognition is personal. But now the motivation has changed. The story is not about ego. It’s about sacrificing to help the cause. It’s a story that matches the donor’s orientation.

Advancing the reframed hero story

Even for the low-ego/high-social donor, heroism is still powerfully attractive. The hero is still a universal archetype. But matching the donor’s natural orientation requires reframing. The story is translated. But it’s still a hero story.

Of course, using a Caregiver story for these donors is easier. No reframing is needed. But this has its limits. The Caregiver fits with small, scattered, emotional-impulse gifts. Large transformational gifts need a hero story. Reframing helps the heroic gift match the donor’s personality.

Gender stories

The right framing depends on the individual donor. It depends on the donor’s archetype orientation. However, gender and class issues may influence this. For example, positive female characters were traditionally restricted. Men could be admirable Heroes, Rulers, Jesters, Explorers, and Outlaws. But not women. Women were restricted to the social/order characters. These are Caregiver, Lover, Everyman, and Innocent.

In the Caregiver story, gifts are small, dispersed acts of kindness. Such gifts may also be expressions of love. This is the Lover-Caregiver story. Or they may show connection to the shared group. This is the Everyman-Caregiver story. Giving can also express faith and trust. This is the Innocent story.

These stories share a common theme. A small gift means just as much as a large one. These gifts could make some impact, but impact isn’t really the point. The point is to express love, solidarity, or trust. These stories fit small, regular, dispersed giving. But they don’t fit with a large, focused, transformational gift. That gift is the gift of the hero story.

Gender statistics

Gender differences in giving match these traditional stories. Women are more likely to make many small gifts to a wider variety of charities. This is true in current giving.[5] It’s true in estate giving.[6] This matches the Caregiver story.

Men are more likely to make fewer, but larger, gifts. They’re more likely to focus on one specific cause or organization. This matches the Hero story.

However, this traditional gender difference may be changing. For example, a private foundation is a high-ego gift. Typically, the foundation lives forever and is

- Named for the donor

- Controlled by the donor, and

- Required to follow the donor’s rules forever.

For years, estate gifts to private foundations were dominated by men. However, women’s use of private foundations has increased dramatically. In the most recent years, this gender difference has disappeared.[7]

Wealth

The individual hero story may be naturally attractive to those with greater wealth. For others, it may require reframing. One study illustrated this. Some people received this request.[8]

“Sometimes, one person needs to come forward and take individual action. This is one of those times. Take individual action. Donate today.”

Others received this version:

“Sometimes, one community needs to come forward and support a common goal. This is one of those times. Join your community. Donate today.”

Which worked better? It depended. It depended on wealth. For wealthy donors, the high-ego, individual-focused heroic message worked better. For those with lower wealth, the high-social, community-focused heroic message worked better.

Major gifts are gifts from wealth holders. Wealth holders are used to controlling an outcome. They’re used to making an impact. The individual hero story is a natural fit. Effective major gift messages can differ from small gifts messages. The donor’s hero story matches the major donation.

Start with natural archetypes

The goal is to advance the donor’s hero story. This is different from creating the donor’s hero story. Advancing starts wherever the donor is right now. If a person identifies with a particular archetype, advancing starts with that archetype. But it doesn’t stop there.

Effective fundraising then combines it with a philanthropic archetype. For smaller donations, it’s combined with the Caregiver archetype. For larger donations, it’s combined with the Hero archetype.

Any personality can fit with some version of the hero story. Professor Lawrence Walker explains, “Heroism is not characterized by a single personality profile; rather multiple types of personality profiles were found to be associated with heroism with the dynamic interplay between situational and personological variables being implicated.”[9]

The “personological variables” differ with each donor. These reflect the donor’s natural orientation. The fundraiser’s role is to create matching “situational variables.”

The fundraiser creates a compelling giving opportunity. This allows the donor’s latent heroism to emerge. The fundraiser is the sage who guides the donor through the hero’s journey.

Hero-archetype combinations

Any archetype can be combined with the donor hero.[10] The bordering archetypes are an easy fit. The Creator-Hero brings into being a new project. He helps design it. He helps create it. Entrepreneurs are natural creators. They love the personal involvement of such hands-on philanthropy. The Magician-Hero uses philanthropy to magically transform reality. The impact should create awe and wonder.

Making the Hero story fit with the Caregiver archetype requires managing the ego-social conflict. The same strategy helps the Caregiver’s border archetypes fit with the Hero story. Thus, the Everyman-Hero and Lover-Hero become possible.

Other combinations can also work. These are closer to the Hero archetype on the axes, so these can be even easier. For example,

-

- The Ruler-Hero

This fits the board member donor receiving position and authority. - The Outlaw-Hero

This fits the social change donor railing against the system. - The Explorer-Hero

This fits the donor giving for innovative research. - The Sage-Hero

This fits the donor giving for education or religious teaching. - The Innocent-Hero

This fits the donor giving from blind trust or faithful obedience. - The Jester-Hero

This fits the ice bucket challenge or “Movember” campaign donor.[11]

- The Ruler-Hero

The point is not just to match the natural archetype. The point is to start there and then move to the hero story. But the starting point helps guide the relevant messages. Detailed accounting fits the Sage-Hero. But it’s needless for the Innocent-Hero. Outrage against the system matches the Outlaw-Hero. But it wouldn’t match a Jester-Hero.

The organization archetype

Each archetype can be a starting point. It makes a particular flavor of hero story. This applies to the donor’s natural archetype. But it also applies to the charity.

Each organization will likely fit a natural archetype. A charity might focus on social change, discovery, wisdom, art/creation, suffering, or community building. Each has its own natural archetype. Social change matches the Outlaw. Discovery matches the Explorer. Wisdom matches the Sage. Art and creation match the Creator/Artist. Easing suffering matches the Caregiver. Building community matches the Everyman.

This organizational identity can help. It will naturally attract donors with a similar orientation. This creates a competitive advantage in fundraising.[12] But this natural advantage won’t lead to major gifts by itself. It does so only when this identity is converted into a related donor-hero story. Fortunately, this is always possible. For every archetype, there’s a hero story for that.

Summary

The hero is not the only archetypal character. However, among the twelve archetypal characters only two are inherently philanthropic. The Caregiver encourages small, dispersed, regular giving. The Hero matches large, focused, transformational giving. Major gifts fundraising must advance the donor’s hero story.

However, not every donor will naturally identify with the hero. Resistance may come from gender roles, class, or just individual personality. Other characters may match better.

The effective fundraiser starts with this natural orientation but doesn’t let the story stop there. The fundraiser moves this natural story into a hero story. Sometimes this means reframing the hero story. This requires wisdom. This requires a sage who guides the donor through the hero’s journey.

Footnotes:

[1] Publicity will be particularly attractive to those with this natural orientation. See, e.g., Cox, J., Nguyen, T., Thorpe, A., Ishizaka, A., Chakhar, S., & Meech, L. (2018). Being seen to care: The relationship between self-presentation and contributions to online pro-social crowdfunding campaigns. Computers in Human Behavior, 83, 45-55.

Tan, J., Yan, L. L., & Pedraza-Martinez, A. (2020, January). How to share prosocial behavior without being considered a braggart? In Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 3941-3950. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/64224/0389.pdf

[5] For U.S. data see Andreoni, J., Brown, E., & Rischall, I. (2003). Charitable giving by married couples: Who decides and why does it matter? Journal of Human Resources, 38(1), 111-133. For UK data see Piper, G., & Schnepf, S. V. (2008). Gender differences in charitable giving in Great Britain. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 19(2), 103-124. [6] James, R. N., III. (2020). American charitable bequest transfers across the centuries: Empirical findings and implications for policy and practice. Estate Planning and Community Property Law Journal, 12, 235-285 [7] Id. p. 264. [8] Whillans, A. V., Caruso, E. M., & Dunn, E. W. (2017). Both selfishness and selflessness start with the self: How wealth shapes responses to charitable appeals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 70, 242-250. [9] Walker, L. J. (2017). The moral character of heroes. In S. T. Allison, G. R. Goethals, & R. M. Kramer (Eds.), Handbook of heroism and heroic leadership (pp. 99-119). Routledge. p. 115. [10] This matches the approach advocated by Pearson (1991). She also uses a circular arrangement of twelve archetypes but replaces the Hero character with the Warrior character. She excludes the Hero character because, “All twelve archetypes are important to the heroic journey, and to the individuation process.” Pearson, C. S. (1991). Awakening the heroes within: Twelve archetypes to help us find ourselves and transform our world. HarperOne (Harper Collins). p. 7Thus each of the twelve archetypes are simply alternative ways of telling a hero story. In the fundraising context, this means each are alternative ways of telling a donor-hero story.

[11] However, the jester is a problematic charitable character. For example, if volunteers’ related social media posts include humorous facial expressions, rather than serious or smiling ones, others view the volunteers as being less sincere in their support of the organization and are also less supportive of the organization themselves. Daniels, M., Kristofferson, K., & Morales, A. (2018). I’m just trying to help: How volunteers’ social media posts alter support for charitable organizations. ACR North American Advances. https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/v46/acr_vol46_2412150.pdf [12] For a comparable concept, see Chapman, C. M., Louis, W. R., & Masser, B. M. (2018). Identifying (our) donors: Toward a social psychological understanding of charity selection in Australia. Psychology & Marketing, 35(12), 980-989. p. 986. (“First, identity research will help fundraisers understand which identities a particular type of charity should make salient in campaign materials to uplift response rates.”)