What’s it about?

An effective fundraising story isn’t just a good story. It must do something. It must lead to a gift. This means the story must be, to some extent, a story about the gift. It must be, in some way, a story about the donor and the donor’s action.

The ask in the narrative arc

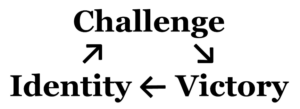

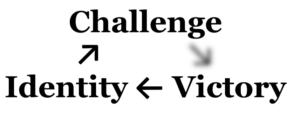

A typical narrative arc progresses through

- Backstory and setting

These establish motivation from the main character’s original identity. - The inciting incident

This presents the main character with a challenge. - Climax and resolution

These show the main character’s victory and altered identity.

In story, the inciting incident must force a response. Otherwise, it fails. In fundraising, an ask must force a response. Otherwise, it fails. But in fundraising it’s not enough to get just any response. We want a specific response. We want a gift. We want a “yes.”

Getting to “yes” with fundraising story

So, how do we get there? The ask presents a challenge to the donor. In story, this challenge happens at the inciting incident. It forces a choice in response to a crisis (threat or opportunity). The effective challenge does not stand alone. It’s part of the full story cycle. The challenge must link to each element in the story cycle.

The donor’s original identity (people, values, or life story) must link to the challenge. For example, the crisis prompting the challenge may be a threat or opportunity for the donor’s people or values. It’s a threat or opportunity for the donor’s sources of identity.

Also, the donor may identify as the kind of person who accepts such challenges. He may be the type of person who says “yes” to the gift because

- Other people like the donor make gifts like this.

- The donor’s values support making the gift.

- The donor’s life story links with the gift.

In each case, a source of the donor’s original identity (people, values, or life story) connects to the challenge.

The challenge for the donor comes at the fundraising ask. This must promise a personally meaningful victory. It promises a solution to the crisis.

The promised victory is meaningful if it will result in an enhanced identity for the donor. This can be internal (private meaning) or external (public reputation). It can also be both.

The challenge must promise a victory

In story, the challenge is the inciting incident. This starts with a disruption. The disruption can be negative. But it comes with a promise. The promise is the hope of a solution. It’s the hope of restoring the balance.[1] It’s the hope of a victory.

In fundraising, the effective challenge may be disrupting, but it comes with a promise. That promise is the same. It’s the hope of a victory. That promise answers the question, “What changes if I give?”

This may seem like a simple step. And it can be. But there are many ways to do it wrong.

Victory barriers: Fuzzy victory

Compelling story evokes a clear image. This requires a clear link from a clear challenge to a clear victory. If the goal isn’t easy to visualize, it won’t be motivating. A vague or uncertain victory won’t work.

There can also be a different problem. The charity’s goal might be clear. The donation request might be specific. But the connection between the request and the goal can still be vague or uncertain.

In either case, the problem is this. The “ask” fails to answer an important question. “What changes if I give?”

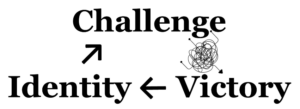

Victory barriers: Complicated stories

“What changes if I give?” If the ask doesn’t answer this question, it doesn’t promise a victory. It’s unlikely to be compelling. Sometimes another problem arises. The answer is just too complicated. The connection to a victory is too confusing.

The problem is not that this complexity isn’t real. The problem is that it doesn’t work. A complicated, technical explanation is exhausting. It also triggers the wrong system in the brain. It triggers the analytical, error-detection system. This blocks a social-emotional response. So, it won’t motivate a gift.

A gift must first be motivated by simple, social-emotional story. Afterward, it’s fine to make complexity available. This can confirm the original social-emotional decision. It can show that there were no rational, logical errors. But the motivating story can’t be complex. Compelling story is simple. It evokes a clear image.

Victory barriers research: Complexity kills giving

In fundraising, complexity is the enemy. More information is not better. One study tested fundraising appeals with different levels of information. The researchers found, “While individuals increase their donations when they perceive an intervention to be more effective, increased knowledge about the project decreases donations.”[2]

Why? The researchers explained, “Factual information about aid effectiveness that may be arduous to process, both with regard to content and length, might dampen the emotional reaction of donors.”[3]

Force-feeding facts doesn’t work. It changes a social or emotional story into a technical report. A social or emotional story triggers empathy and sharing. A technical report triggers analysis and error detection.

Another study focused on major donors. These were the largest and most active donors to an environmental charity. It shared the charity’s new 36-page plan. The plan shifted, “Its approach from land conservation to a more complex, systems‐oriented approach.”[4]

Technical experts approved this complexity. The donors? Not so much. 85% expressed serious concerns. The problem was this: “When compared with the tangibility of prior gifts, these measures seemed too intangible to feel confident funding … At its core, the grander vision was too broad for any one individual donor to feel like they personally can make the sort of impact that matters.”[5]

In fundraising, impact is not an issue of complex technical reports. It’s an issue of social-emotional story. Forcing complex facts or concepts makes the story too complicated. A complicated story won’t evoke social emotion. Without social emotion, there is no gift.

Victory barriers research: Complexity conflict

Complexity kills giving. So why do many charities keep doing this wrong? It’s not an accident. The problem comes from a specific source. Stories get complicated when charity managers get involved.

Charity managers deal with society’s most difficult problems. They live in a world of complexity. They are technical experts. They have so much information. They naturally want to share it. They feel that the donors “need to understand.” But this complexity ruins fundraising story. The desire to push complexity leads to conflict with fundraising.

One study examined a homelessness charity. But it used a unique approach.[6] It explored the charity’s internal culture using ethnography. What it found was conflict. The researcher explained, “Head of Fundraising shares this dilemma: “we simplify everything, that is, sort of the only way we can raise money quickly. We have to simplify!” Currently, fundraising is based on the slogan ‘Give them a bed for the night!’. This, argues another senior manager, ‘goes against all I have learnt about social work’ as it refers to simple solutions at individual level although the issue ought to address profound structural and societal issues.”

This is a conflict. What is the charity managers’ proposed solution? Re-educate the donor. They believe, “The accountability relationship should, in their view, involve educating the donor: ‘we need to work with the general public’s view about homeless people.’”

Charity manager’s desperately want to share their worldview. It’s a worldview of complexity. They want to force-feed this technical complexity to donors. Unfortunately, this has a dangerous side effect. It kills fundraising story.

Victory solutions: The fundraiser as translator

Complexity kills giving. So, what’s the solution? Translation. It’s not that the complexity isn’t real. It’s that it doesn’t work. Effective fundraising must translate. It must convert this complexity into a representative story. It must transform it into a simple story about the donor’s gift.

One study identified the key factors in successful major gift asks.[7] The researchers explained, “they rely on the fundraisers’ skills in reframing complex issues and finding alignment between the recipient organisation’s needs and the philanthropic aspirations of the donor.”[8]

The successful fundraiser excels at “reframing complex issues.” She converts complexity into a simple story. It’s a story about the “philanthropic aspirations of the donor.” It’s a story about the donor and the donor’s gift.

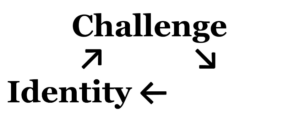

Victory barriers: Missing victory

Sometimes the connection between a gift and a victory is fuzzy or complicated. Sometimes the victory itself is vague or uncertain. But it can get worse. Sometimes there isn’t any victory at all.

The essence of this request is, “We do good work. We need money. Please give.”

For the charity, this is a natural request. Why? Because it’s a story about them. It’s about their identity, their challenges, and their needs. It’s also easy. It’s a message that applies to every charity, everywhere, all the time.

It’s a compelling story – for the charity insiders. The donor gives to honor their heroic work. The donor gives because they’re so wonderful. This message may sound great to the charity insider. But it’s not that compelling for the donor. In this story, the donor is just a bit player.

Moving beyond this message can be difficult for charity insiders. They have to set aside the story that they love. They have to put themselves in the donor’s shoes.[9] This isn’t easy.

Victory barriers: Fundraising without victory

A compelling ask answers the question, “What changes if I give?” But what if there’s no answer? What if the answer is:

- “Nothing”

- “I don’t know,” or

- “That’s not your concern. You just leave that to the experts.”?

The donation story has no victory. Can a fundraising ask still raise money? Yes. Donors can still give just because of who they are, not what the gift does.

Donors can give just because of their identity connections. They might identify with the charity, the cause, or the act of giving. Giving can still happen. But these gifts will tend to be small.

Think of it this way. Suppose you give $100 just because you like the charity. Maybe it connects with your people, values, or life story. That’s fine. But how likely is it that you will grow to like that charity 10 times more than you already do? Pretty unlikely. So, how likely is it that you will give $1,000 or $10,000 instead of $100? The answer is the same. Pretty unlikely.

Without a victory, the only gift that makes sense is the small gift. This is the “pat on the head” gift. It’s the social compliance gift. It’s like trying to win the “participant” award. It can motivate action, but not much. It can motivate a gift, but not a large one.

To get the rest of the gift, we need the rest of the story. The 10x or 100x gift must do something different. It must do something specific, visualizable, and compelling. It must promise the hope of a victory. Increasing the size of a gift means offering a compelling victory. This can improve the fundraising ask. It can even happen after the donation.

Victory upgrades: Snatching victory from the jaws of the small gift

Suppose a donor has made a gift. Maybe they’ve written a check. Maybe they’ve included your charity in their will. Regardless, after expressing gratitude, it’s still possible to increase the size of the gift. How? It starts by adding a victory. It can even start by asking the donor to add a victory. For example,

- “Have you ever thought about how you would like this gift to be used?”

- “Tell me about your goals for this gift. What kind of impact do you want to make?”

These questions lead to conversations about outcomes. Outcomes have price tags. An outcome with a price tag leads to a challenge with a victory. It can turn the gift into the initial gift. It can lead to a more compelling ask. For example, “The reason I ask is this. You remind me of another donor. She felt the same way you do. So, she decided to …

- Establish a permanent scholarship fund.

- Sponsor this operation for a week.

- Fund a project that … [insert victory outcome].

What are your thoughts about doing that?”

Conclusion

A story needs an inciting incident. Fundraising needs an ask. Both work better when they promise the hope of a victory. A challenge promising a victory makes a compelling ask. It makes the challenge part of a compelling fundraising story.

Footnotes

[1] “Therefore, the Inciting Incident first throws the protagonist’s life out of balance, then arouses in him the desire to restore that balance.” McKee, R. (1997). Story: Substance, structure, style and the principles of screenwriting. Regan Books. p. 192.

Related Resources:

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- Opportunities vs. Problems: Which will your donors support?

- The 3 Key Elements of a Good Fundraising Story