At the heart of philanthropy is story.

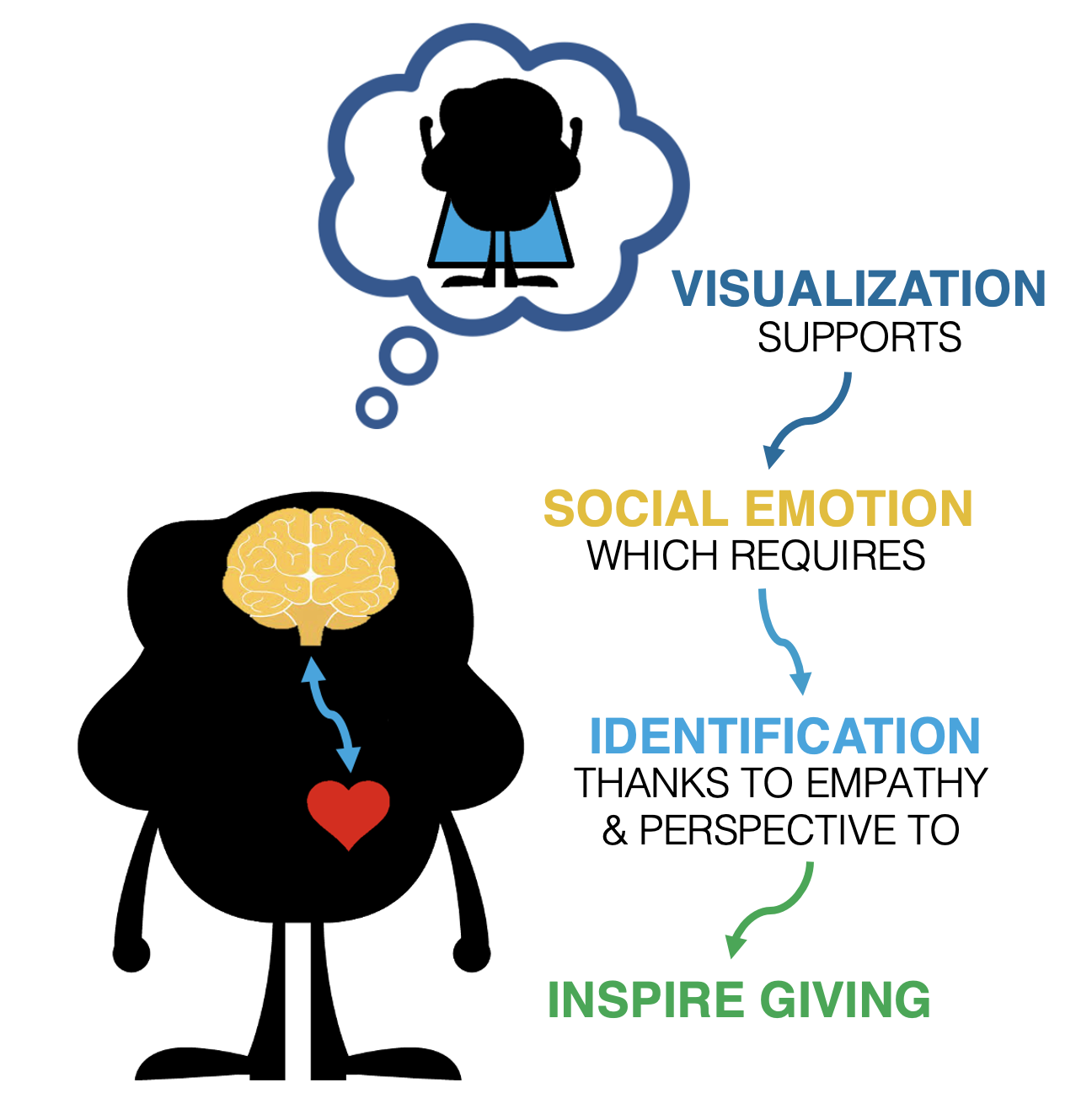

Story starts with character. Without a relatable character, the fundraising story is dead. To be relatable, the donor must identify with the character. The donor must see things from the character’s perspective. (The image must be clear.) The donor must have empathy for the character’s situation. (The image must evoke social emotion.)

Story character

A story needs character and plot. But it starts with character. A plot might be good. It might have a challenge. It might have a victory. But if we don’t care about the character, plot doesn’t matter.

In an effective story, we identify with the character.[1] We can see things from their perspective. We have empathy for them. As an equation, this would be

Identify = Perspective + Empathy.

Fundraising story character

In brain imaging, donating is predicted by social-emotional valuation.[2] This, in turn, depends on both perspective and empathy.[3] In other words, donors must identify (perspective + empathy) with the character. This changes a story into the donor’s story.

Identifying with a character starts by visualizing the character. If we can’t envision the character, we can’t take the character’s perspective. If we can’t take the character’s perspective, we won’t have empathy.

A vague story doesn’t create social emotion. Neither does a complicated or confusing one. These don’t work because they don’t trigger visualization. To feel something, we must first see something. But what we see must also make us feel. A character must be clear, but it must also be empathetic.

The goal

The external goal of fundraising story is a gift. But the internal goal is this:

Evoke a clear image that generates social emotion.

This internal experience leads to the external gift. How do we make this happen? It starts with a compelling character. This means

- Make it specific.

- Make it simple.

- Make it empathetic.

Let’s look at each character element in depth.

1. Make it specific

Character details in fundraising

Revealing specific details about a character can help. It can make mental images easier to form. This is powerful for fundraising. Experimental results show this.

In one experiment, people could give money to another unknown person. Some were also told the recipient’s last name. This added detail increased average gift size by almost half.[4] In another experiment, some people could also see the recipient. This roughly doubled average gift size.[5]

The same idea also works in fundraising experiments. In one, people were asked to donate for a child in medical need. Some people also received the child’s name, age, and picture. These details increased the likelihood of donating from 61% to 90%.[6]

Why character details work

In fundraising story, adding character details can make a big impact. How does this work? Researchers mapped out the steps.[7]

They began with a simple experiment. People were asked to donate for a child in Africa who was in danger of starvation. Some were also given the child’s name and picture. This addition doubled willingness to donate. No surprise there.

But this experiment dug deeper. It asked detailed questions. It used statistical path analysis. This revealed the underlying steps. These were

- Adding character details increased the clarity of the mental image.

- This enhanced image increased sympathy.

- This increased sympathy drove greater donations.

The underlying mental pathway was this:

Character details[8] → Mental Image → Victim-focused emotion (Sympathy) → Donation

These research methods were quite different from brain imaging. But the answers were almost identical.

In brain imaging, donations require

- Taking another’s perspective and

- Having empathy for that person’s circumstances.[9]

In this path-analysis research, donations require

- Picturing the other person and

- Feeling sympathy for that person.

Again, different methods give similar answers.

2. Make it simple

The one outweighs the many

In Star Trek II, Dr. Spock sacrifices his life in the climax scene. In his parting words, Spock says, “Logic clearly dictates that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few.”[10]

Kirk responds, “Or the one.”

As a matter of logic, this is true. It’s better to help many people instead of just one. But as a matter of fundraising story, this isn’t true. Why? Because an individual can be a great character. A random crowd can’t. Experimental research confirms this.

The one outweighs the five

In one experiment, people could donate to help children in a famine. For some people, donations helped five pictured children. For other people, donations helped only one of the five children. Asking for gifts for just one child worked dramatically better. Donations to help one pictured child were almost double those to help five.[11]

Why did this happen? It’s complicated. No, the answer isn’t complicated. The answer is, “It’s complicated.” The researchers explained, “As the number of victims increases, the mental representation becomes more diffuse and abstract until it is difficult to attach emotional meaning to it.”[12]

When the character changed from one child to five, the mental image became complicated. The emotion disappeared. The donations fell.

The one outweighs the eight

In another experiment, people could donate to buy life-saving cancer drugs. For some people, the drugs would save eight children. For other people, they would save only one. The total cost was the same in both cases. The requests included the children’s names, ages, and pictures.

What happened? With the story saving one child, 90% donated. With the story saving eight children, only 58% did.[13]

The simple eight outweighs the complex eight

And then things got even weirder. Another group also got the request for eight children. But this time, their names, ages, and pictures were removed. The result? The likelihood of donating increased from 58% to 77%!

Taken together this means

- 90% donated to a story of one child with name, age, and picture.

- 77% donated to a story of eight children without names, ages, or pictures.

- 58% donated to a story of eight children with eight names, ages, and pictures.

Why did this happen? Again, the answer is, “It’s complicated.” As the story grew more complex, donations fell. A story with eight main characters is complicated. Adding even more details – eight names, ages, and pictures – didn’t help. It made a complicated story even more complex. Donations fell even more.

The one cohesive group outweighs the many individuals

Having six or eight different main characters is too much for a story. It’s too complicated. But there is a solution. Presenting many individuals as one, single cohesive group simplifies the story.

In one experiment, people could donate to help educate six children in Africa.[14] The children’s names and pictures were included. But for some people, the children were described as siblings from the same family. This addition more than doubled donations. Instead of six random characters, the story had a single, cohesive unit.

Another experiment asked for donations for butterflies.[15] The gift would help buy a shelter to protect 25 rare butterflies. For some people, the butterflies appeared on screen as a single, orderly unit. They flew in unison. For other people, they flew randomly from different locations at different speeds. Donations with the unified group butterfly video were two-thirds larger.

Another experiment asked for donations for gazelles.[16] The gift would help buy a fence to protect 200 gazelles. People were asked, “How much the gazelles typified what it means to be a tight group.”[17]

The answer to this question predicted donations. Viewing the gazelles as a more unified group boosted emotional concern. This increased the gift.

The underlying goal is to

- Evoke a clear image

- That generates social emotion.

Having 5, 6, 8, 25, or 200 different main characters is too complicated. The image isn’t clear. But a single cohesive group creates a single character. This makes a clear, simple image.

This works. If. It works if the image generates social emotion. It works if the image is empathetic.

3. Make it empathetic

Only the empathetic one outweighs the many

One experiment asked about donating for an environmental problem. For one group the problem was described as, “fertility loss due to pollution threatens reptiles on the Mexican coast”.[18]

In this group, 24% of people were willing to donate. For other people, the word “reptiles” was replaced with one specific reptile. If “reptiles” was replaced with “turtles,” 34% were willing to donate. If “reptiles” was replaced with “lizards,” only 17% were willing to donate.

Picturing “turtles” is easier than picturing “reptiles.” And the image evokes empathy. This works. Picturing lizards is also easier. But the image doesn’t evoke much empathy. This doesn’t work. It sharpens the focus of the image. But it sharpens the focus on an unsympathetic image.

Another experiment showed this with children.[19] It copied the previous experiment helping six children in Africa. As before, some people were told that the children were siblings. As before, this more than doubled donations.

But others were also told that the children were in prison for committing crimes. Donations fell. More importantly, this changed the effect of presenting the children as siblings. Doing this now cut donations by more than two-thirds.

Why? Picturing a family is easier than picturing six individual characters. It sharpens the focus. If the characters are sympathetic, this helps. If they are unsympathetic, this hurts. Turtles and kids are sympathetic characters. Lizards and criminals aren’t.

Details help only the empathetic character

One experiment asked people to donate for a learning experience. It benefited a financially needy, gifted child.[20] Half of the people were also given the name and picture of the child. Adding this nearly quadrupled willingness to donate.

Why? The character details increased sympathy for the child. This sympathy increased willingness to donate.

But details don’t help if the character doesn’t evoke empathy. Another version of the experiment changed one thing. The child was not in financial need. In this version, adding the name and picture of the child didn’t help. Why? Because it had little effect on sympathy.

Visualizing the child became easier, but the character faced no challenge. There was no reason for social emotion. So, more details didn’t trigger more giving.

Both steps

Effective fundraising story

- Evokes a clear image

- That generates social emotion.

Visualizing a story’s character is the first step. A simple and specific image works the best. But if the image doesn’t generate social emotion, it won’t lead to a gift. A clear image is important. Using visual media can sometimes help.[21] But without the rest of the story, it doesn’t matter.

Other applications

The rules still apply

These examples are great if you can tell sympathetic stories about specific beneficiaries. But what if you can’t? What if your cause isn’t puppies, turtles, or kids? What if your characters are employees, donors, or concepts? Even then, the same rules still apply. The goal is still the same:

- Evoke a clear image

- That generates social emotion.

If your story’s character or outcome is vague or fuzzy, it won’t evoke a clear image. If it is complex and technical, it won’t evoke a clear image. In either case, your story won’t motivate donors. It can’t. It doesn’t even get to the first step.

It’s complicated

The goal is to evoke a clear image that generates social emotion. But clarity isn’t easy. Simplicity isn’t simple.

Michael Hauge is a well-known script advisor. He’s spent over 35 years consulting with professional storytellers and business leaders. What’s the number one problem he encounters? He explains, “Their stories are way too complicated.”[22]

What about your story? Does it create a clear, simple, visual image? Is that image emotionally compelling for donors? If not, you might still enjoy telling it. But it won’t do much for fundraising.

Footnotes

[1] As a general concept, one researcher explains the role of identification with a character this way. “Telling a compelling story involves creating convincing characters, using enticing and enthralling plotlines and understanding one’s audience. Stories resonate with audiences because they have narrative fidelity, generate points of identification, and have recognizable story structure: a beginning, middle and end.” Kent, M. L. (2015). The power of storytelling in public relations: Introducing the 20 master plots. Public Relations Review, 41(4), 480-489. p. 484. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.05.011

As a specific example of the importance of identification from fundraising, an in-depth investigation of donor motivations for giving to university athletic programs found that, “‘vicarious achievement’ was a primary motivational factor for donors to university athletic programs. Kim, S., Kim, Y., & Lee, S. (2019). Motivation for giving to NCAA Division II athletics. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 28(2). 77-90.

[2] Hare, T. A., Camerer, C. F., Knoepfle, D. T., O’Doherty, J. P., & Rangel, A. (2010). Value computations in ventral medial prefrontal cortex during charitable decision making incorporate input from regions involved in social cognition. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(2), 583-590; Moll, J., Krueger, F., Zahn, R., Pardini, M., de Oliveira-Souza, R., & Grafman, J. (2006). Human fronto–mesolimbic networks guide decisions about charitable donation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(42), 15623-15628; Tusche, A., Böckler, A., Kanske, P., Trautwein, F. M., & Singer, T. (2016). Decoding the charitable brain: empathy, perspective taking, and attention shifts differentially predict altruistic giving. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(17), 4719-4732.

[3] Hare, et al. (2010); Tusche, et al. (2016).

[4] Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2008). What’s in a name? Anonymity and social distance in dictator and ultimatum games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 68(1), 29-35.

[5] Bohnet, I., & Frey, B. S. (1999). The sound of silence in prisoner’s dilemma and dictator games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 38(1), 43-57.

[6] Kogut, T., & Ritov, I. (2005). The singularity effect of identified victims in separate and joint evaluations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 106-116.

[7] Dickert, S., Kleber, J., Västfjäll, D., & Slovic, P. (2016). Mental imagery, impact, and affect: A mediation model for charitable giving. PloS One, 11(2), e0148274.

[8] The researchers used the word “identifiability.” This referenced when participants received identifying character details, i.e., the child’s name and picture. I omit this phrasing to avoid confusion with the concepts of identifying, identification, and identity used in a different application (i.e., connection with the self) in this article series.

[9] Hare, T. A., Camerer, C. F., Knoepfle, D. T., O’Doherty, J. P., & Rangel, A. (2010). Value computations in ventral medial prefrontal cortex during charitable decision making incorporate input from regions involved in social cognition. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(2), 583-590.

[10] Bennett, H. (1982). Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan [movie script]. http://www.dailyscript.com/scripts/startrek02.html

[11] Study 1 in Dickert, S., Kleber, J., Västfjäll, D., & Slovic, P. (2016). Mental imagery, impact, and affect: A mediation model for charitable giving. PloS One, 11(2), e0148274.

[12] Dickert, S., Västfjäll, D., Kleber, J., & Slovic, P. (2012). Valuations of human lives: normative expectations and psychological mechanisms of (ir)rationality. Synthese, 189(1), 95-105. p. 101.

[13] Kogut, T., & Ritov, I. (2005). The singularity effect of identified victims in separate and joint evaluations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 106-116. Table 1.

[14] Smith, R. W., Faro, D., & Burson, K. A. (2013). More for the many: The influence of entitativity on charitable giving. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(5), 961-976. Study 2.

[15] Id. Study 1.

[16] Id. Study 3.

[17] Id at 967.

[18] Kahneman, D., & Ritov, I. (1994). Determinants of stated willingness to pay for public goods: A study in the headline method. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 9, 5-38.

[19] Smith, R. W., Faro, D., & Burson, K. A. (2013). More for the many: The influence of entitativity on charitable giving. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(5), 961-976. Study 4.

[20] Kogut, T., & Ritov, I. (2005). The singularity effect of identified victims in separate and joint evaluations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 106-116.

[21] One experiment showed that identical text led to more donations if it was placed in stick figure thought bubbles in a comic form. [Xiao, Z., Ho, P. S., Wang, X., Karahalios, K., & Sundaram, H. (2019). Should we use an abstract comic form to persuade? Experiments with online charitable donation. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), 1-28.]

In another example, one study showed that “content viewed on a Virtual Reality platform, when compared against a traditional two-dimensional video media platform, increases empathy, increases responsibility, and instigates higher intention to donate money and volunteer time towards a social cause.” Kandaurova, M., & Lee, S. H. M. (2019). The effects of Virtual Reality (VR) on charitable giving: The role of empathy, guilt, responsibility, and social exclusion. Journal of Business Research, 100, 571-580. p. 571.

[22] Hauge, M. (2018). What does your hero want? [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.storymastery.com/character-development/what-does-your-hero-want-outer-motivation/

Related Resources:

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- At last, the one big thing every fundraiser needs to know to be successful

- At last, the Not-So-Secret Formula for Raising Major Gifts