A compelling fundraising challenge will connect with the donor’s identity. This begins with backstory. Backstory connects the cause, charity, or project with the donor’s history, people, or values. This encourages giving.

But for larger gifts we need more. We need a challenge that promises a victory. And not just any victory. We need a victory that is personally meaningful for the donor. We need a victory that delivers an enhanced identity. And how do we discover this? Socratic fundraising can help.

The ultimate victory question

There are many “victory” questions. An open-ended one is this:

There are many “victory” questions. An open-ended one is this:

“What would you like to accomplish with your money that would be meaningful to you?”[1]

This question is powerful. It connects

- Challenge (“your money”),

- Victory (“accomplish”), and

- Identity (“meaningful to you”).

This one question contains the full story cycle. It really says, “Tell me your ideal donor-hero story.”

Asking this victory question can be powerful. When it works, it quickly identifies a compelling outcome for the donor. It gives the fundraiser the precise parameters for the perfect ask.

But it doesn’t always work. Giving an accurate answer can be difficult. Many will respond, “I don’t know.” Others might say, “I’ll have to think about that.” Or the answer might be something the charity can’t do. Other types of “victory questions” can address these issues.

Narrowing the victory question to giving

Another version restricts the answer to philanthropy. It asks, “What would you like to accomplish with your giving that would be meaningful to you?”

This question avoids answers like, “providing a secure future for my family.” That is a meaningful thing a person can do with money. But it’s not usually something the charity can offer.[2]

The tradeoff is this: This version changes the financial reference point for the challenge. It doesn’t bring to mind the big bucket of “your money.” It references only the small bucket of “your giving.”

Another version lightens the question. It asks, “What would you like to accomplish with your giving?”

This question is easier. The donor can define a victory without contemplating the meaning of life.

The tradeoff is this: Meaning questions are hard questions. But they’re powerful questions. The ultimate benefit from donating is enhanced identity. This is meaning (private) or reputation (public). The typical use for more money – more consumption (houses, cars, holidays) – can’t deliver meaning. In sales terms, meaning questions lead with “product” benefit.

Narrowing the victory question to giving here

Other versions restrict the story to one cause or charity. For example,

- “What would you like to accomplish with your giving in [this cause]?”

- “What would you like to accomplish with your money at [this charity] that would be meaningful to you?”

The original question fits broad-mission charities. A community foundation can accommodate most any cause. So can a large research university. But many charities represent a narrow cause. Triggering a conversation about an unrelated charitable passion might not be helpful.

The tradeoff is this: The question narrows the scope of the relationship. It can imply, “I’m not your life advisor. I’m not your wealth advisor. I’m not even your philanthropy advisor. I’m only here to talk about my organization.”

This may feel more efficient. But it also limits the possibility for a broader conversation. These more comprehensive discussions are powerful. They can lead to larger gifts.

Challenges for open-ended victory questions

Open-ended victory questions can be powerful. But they require a lot from the donor. He must know a lot about himself. He must know a lot about possible projects. And he must fit both together to form a compelling goal.

But even if the donor identifies his ideal victory, there’s another problem. This doesn’t work unless the fundraiser has the power to ask for that gift. In many charities, that’s just not reality. Getting such a proposal approved wouldn’t be merely difficult. It would border on offensive. Charity managers can think, “Why isn’t this fundraiser out getting unrestricted cash? Doesn’t she understand we are supposed to make the decisions? Doesn’t she know we are the experts. [Doesn’t she realize we are the heroes here?]”

Now what? What if the fundraiser doesn’t have this kind of freedom? What if the donor doesn’t have this kind of insight?

Moving to the victory menu

Menus can be powerful in fundraising. They provide clear, simple, attractive options. Each option has a specific price. Making an ask becomes less risky. If the gift size doesn’t match, it’s right next to other options.

Menus make decisions easier. They make the outcomes obvious and visualizable. They’re powerful. They’re easier for the fundraiser. Menus contain pre-approved options. Although ordering “off-menu” may be possible, it’s rare.

A victory menu is narrower than an open-ended victory question. But Socratic fundraising is still possible. One experiment showed this.[3] People read about fifteen charity projects across five causes.[4] (This is like an example menu.) Half were also asked to rate the importance of each project.[5] (This is like a “Socratic” menu.)

Everyone was then asked about making unrestricted gifts. Across ten charities tested, the likelihood of giving averaged

- 15% for the simple menu group, and

- 21% for the “Socratic” menu group.

Asking preliminary questions made the menu more powerful.

Defining victory after the legacy gift

Socratic fundraising leads up to a challenge. But what if the donor has already decided on a gift amount? What if he’s already made the gift? Is it too late? Not necessarily.

This is a common issue in legacy fundraising. Often, the charity learns of the gift only after it’s planned. A donor joins the legacy society. Or he fills out a survey revealing the charity is in his will. That’s great! But what if we want to know

- How much is it?

- Can it be more?

These are relevant fundraising questions. But they’re also potentially offensive.

Imagine a family reunion. Great Aunt Rose mentions to her nephew, “I just want you to know, I’ve included you in my will.”

The nephew responds, “That’s great Aunt Rose! Thank you…. Umm, just so I can plan out my future budgets, could you tell me how much I’m getting? And would you consider increasing the amount?”

That feels a little uncomfortable, right? Yet this is the position of many legacy fundraisers. They want to get credit for the gift amount. They want to make it bigger.

The “planning for the future” excuse is common. But it’s a little odd. The charity doesn’t know when the donor will die. By then the estate or the gift may have changed. Sometimes the excuse is about reaching campaign goals. Still, even this may leave some donors unmoved.

Socratic fundraising suggests another approach. Help the donor define a personally meaningful victory. After thanking the donor for the gift, this can start with a question. For example, “Have you thought about how you would like your gift to be used?”[6]

This can lead to conversations about the impact of different gifts. The fundraiser might even share a story about another donor. For example, “The reason I ask is that you remind me of another donor. He was also … [reference personal similarity]. He also cared about … [reference shared values]. He set up a gift in his will to create a permanent endowment. He named it after his mother. The endowment … [describe the impact and the cost].”

The donor learns about gift options. Of course, options have prices. The prices justify talking about the planned gift amount. The prices can also lead to an increase in the gift. Now, there is a reason to give more.

Starting with a larger example gift can help. The donor’s reactions will reveal details about the planned amount. If the price is too high, follow up with less costly options.

Defining victory after the current gift

This approach isn’t limited to legacy fundraising. Cliff Wilkes explains, “If they have a current endowment or gift, I’ll ask, ‘what kind of impact do you ultimately want to have with your scholarship, endowment, etc.?’

This has,

- Opened the door to some meaningful conversations on ways to give,

- Led to larger gifts than what was originally discussed,

- Increased giving to current funds, and

- Led to several planned gifts.”[7]

Helping the donor to define a meaningful victory is powerful. This is true before the gift decision. But it can also be true after the (initial) gift decision.

Victory implications: Increasing the benefit

Questions can uncover a meaningful victory. This makes for a compelling gift. But they can do even more. They can increase the importance of that victory. How? By asking questions about the victory’s implications. For example,

- “What if this goal was accomplished? What would that mean to you?” [This references values.]

- “Why do you think this project is important to the community?”[8] [This reference people.]

- “You mentioned that your grandmother also cared about this cause. What would she have thought about this project?” [This references people and life story.]

The questions get the donor to describe the victory’s results and meaning. They help the donor connect the results to his people, values, and life story. This highlights the enhanced identity benefits from donating.

Victory implications: Research

A meaningful victory delivers donor benefit. Implication questions can remind donors of these benefits. They can get the donor to confirm and restate them.

One experiment tested the effects of doing this.[9] It first asked some people about these personal benefits. It asked, “In your opinion, to what extent can making monetary donations give a sense of fulfillment and personal gratification? (1 = Not at all, 9 = Very much)”

It then asked, “According to some, making charitable donations can give a sense of fulfillment and personal gratification. Several reasons can be found for this feeling: being aware of providing for the community, having a clear conscience, being on the right side, doing a good deed, resting peacefully, not feeling guilty, etc.

In your opinion, what are the three main reasons people could be fulfilled when making donations?”

These questions worked. Asking them increased willingness to donate. The questions highlighted positive implications from giving. This increases giving.

Conclusion

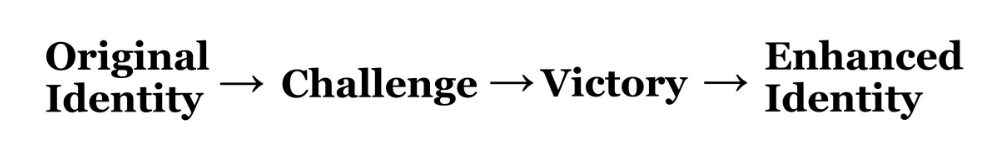

The universal hero story begins in the main character’s original, small world. This is the source of his original identity. He is then faced with a call to adventure. It promises the hope of a victory. He eventually accepts the challenge and wins the victory. He returns as a transformed (internal) and honored (external) hero.

Powerful fundraising includes the same elements. The compelling fundraising challenge links back to the donor’s original identity. It promises the hope of a personally meaningful victory. It moves the donor through the hero’s journey.

Questions can help. They can help connect the challenge to the donor’s original identity. They can help uncover a personally meaningful victory. They can highlight the enhanced identity resulting from the victory. They can advance the donor’s hero story.

Footnotes:

[1] Advancement Resources. (2017, November 15). The power of the pause: Using silence in donor conversations [blog]. https://advancementresources.org/the-power-of-the-pause-using-silence-in-donor-conversations/See also, “What would you want to do with your money that is meaningful to you?” in Shaw-Hardy, S., Taylor, M. A., & Beaudoin-Schwartz, B. (2010). Women and philanthropy: Boldly shaping a better world. John Wiley & Sons. p. 115, quoting from Advancement Resources. (2006). The art and science of donor development workbook. Advancement Resources, LLC.

[2] The exception here would be for those trained in sophisticated planned giving in the U.S. where many instrument combinations actually can provide this outcome along with charitable giving. [3] James, R. N., III. (2015). The family tribute in charitable bequest giving: An experimental test of the effect of reminders on giving intentions. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 26(1), 73-89. [4] The Nature Conservancy– preserve wetlands for wild ducks and other migrating birds,

– protect and restore ancient sequoia and redwood forests in the U.S.,

– protect sensitive coral reefs around the globe

The American Cancer Society

– research for cures to the most deadly cancers,

– provide treatment to patients in need,

– provide public education on reducing the risk of cancer

Your local animal shelter

– provide veterinary care for animals in need,

– increase adoption of shelter pets needing a home,

– investigate and stop animal cruelty in your area

UNICEF

– provide clean water to impoverished children in need,

– provide immunizations to children around the world,

– provide emergency relief to victims of a natural disaster

The Boys and Girls Clubs of America

– provide youth education programs helping with success in school,

– provide youth sports and recreation programs,

– provide youth arts and creativity programs

Related Resources:

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- How to develop a ‘character’ in your fundraising stories in 3 steps — according to Dr. Russell James

- The Importance of Asking Permission to Ask More Questions