Verba docent, exempla trahunt.

“Words teach people, examples compel them.”

– Latin proverb[1]

It’s simple. We want the donor to say, “Yes.” But how? How do we create the conditions that encourage that “Yes.”? Let’s look at theory, experiment, and practice.

Theory: The primal-giving game

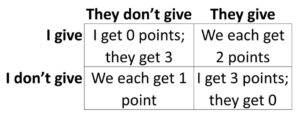

The primal-giving game models the natural origins of giving.[2] In the game, sustainable giving depends on community norms.[3]

- In a reciprocal, sharing community, giving makes sense. Others become more likely to share with givers in the future. Givers benefit from their enhanced public reputation. Giving is a winning move.

- In a non-sharing or non-reciprocal community, giving does not make sense. Others do not become more likely to share. Givers get no benefit from their public reputation. Giving is a losing move.

The right move depends on which world we are in. How can we tell the difference? It’s complicated. In real life, there are many possible games and communities. People may be reciprocal in some, but not in others. Some gifts may help reputation, while others won’t.

We could try to test every alternative. But choosing wrong is costly. The smarter play is this: Follow the examples of others in your community. Examples are powerful. But examples of people like me are even more powerful. The key question is, “What do people like me do?” The answer shows the community norm. The community norm dictates the right move.

Theory: The monomyth

Showing that “people like me make gifts like this” matches the primal-giving game. It also matches the universal hero story (monomyth).[4] It does so by linking the challenge with the full story cycle. That cycle is, Showing that “people like me make gifts like this” connects

● Original identity→ Challenge

Who is “like me?” The answer is personal. It’s subjective. But whatever the answer is, it reveals my identity.[5] If others like me accept a challenge, it links the challenge to my identity. It shows that I am the type of person who accepts challenges like this. I am the type of person who makes gifts like this.

● Challenge→ Victory

These other people also gave. They must have thought it was a good idea. They must have thought their gift would make a difference. That makes it easier for me to believe the same thing. It makes it easier to believe in the hope of victory. This helps link the challenge to a victory.

● Victory→ Enhanced Identity

These other people gave. They must have thought that the promised victory was important. This means two things. First, the victory likely benefits our shared group. Our group is a key source of my identity. Thus, the victory enhances this source of my identity.

Second, other group members will likely appreciate my efforts to achieve this victory. (After all, it was important enough to compel them to give, too.) This appreciation for my gift solidifies my standing within the group.

The gift helps my group. And it helps my standing within the group. Both of these help link the victory to an enhanced identity.

We want the donor to say, “Yes.” That “yes” comes in response to a challenge. The effective challenge is part of the full story cycle. It must be rooted in the donor’s original identity. It must promise a victory that delivers an enhanced identity.

Showing that “people like me make gifts like this” helps. It helps link the challenge with the full story cycle. It helps make the challenge more compelling. It helps the donor move to a “yes.” It works. It works not only in games and myth. It also works in experiments.

Experimental results: Other people

Others’ examples can influence any type of helping. In experiments, they influence giving.[6] They also influence volunteering.[7] They even influence stopping to help a person with car troubles.[8]

Others’ charitable examples can make donating feel like the normal, expected, or default option. Such defaults can influence behavior. For example, describing a gift as an opt-out, rather than an opt-in, increases giving.[9]

Others’ examples can be powerful. But this power increases when the examples are “like me.” If other people “make gifts like this,” that’s informative. If people like me “make gifts like this,” that’s compelling.

One experiment in a law firm found a dramatic result. Mentioning, “Many of our customers like to leave a gift to charity in their will,” more than tripled the share of people who chose to do so themselves.[10]

The story of Sara: People like me

In one experiment, I compared the effects of two messages.[11] One described how “you” could use a charitable gift annuity. The other was identical, except it described how “Sara” had used a charitable gift annuity. This message worked better. People were more interested in making the gift after reading about Sara.

And then things got more interesting. In another test, I used identical language but also showed a picture of Sara. And the results got worse. The example became less persuasive. To learn more, I next tested three more pictures:

- Younger Sara

- Middle-aged Sara, and

- Older Sara.

The result? If the picture was close in age to the subject, it made the example more persuasive. If not, it made the example less persuasive.

But further analysis revealed that this result actually wasn’t about age. It was about identity. Statistically, age mattered only when it changed the answer to this question:

“How much do you identify with Sara? She is [a lot / somewhat / a little bit / not really / not at all] like me.”

If Sara was “like me,” her example was powerful. Otherwise, it wasn’t.

Experimental results: People like me

“People like me make gifts like this.” It’s a powerful fundraising message. Other experiments show this same result.

One experiment used a public radio station pledge drive.[12] New members calling in were told,

- “We had another member; he [or she] contributed $240.”

- This example gift was larger than the typical gift.

- The use of “he” or “she” alternated randomly.

What happened? When the “he” or “she” matched the caller’s gender, average gifts were a third larger than when it didn’t. A single letter “s” made a big difference!

In another experiment,[13] students at a Swedish university were asked for a donation. They were randomly told the following:

- Group 1 was told nothing else.

- Group 2 was told that 73% of university students in Sweden made the gift when asked.

- Group 3 was told that 73% of university students at their university made the gift when asked.

In the first group, 44% donated. In the second, 60% did. In the third, 79% did. As the example became more like the donor, giving increased.

Another experiment used students at an Italian university.[14] They were told, “On average, Italians [or Germans] donate €70 to support this project.”[15] When the example was Italian, donations were nearly 50% greater than when it was German.[16] Again, giving by “people like me” was more influential.

This isn’t just about age, or gender, or nationality. It’s about identity. Researchers call this the “identity congruency effect.”[17] When “people like me make gifts like this,” the examples are powerful.

More results: People like me

These same types of results show up in many experiments with giving[18] or volunteering.[19] One lab experiment reported,

“Peer effects are positive, with subjects’ donations increasing in those of labmates and past subjects. However, subjects did not respond to … gifts by an anonymous donor.”[20]

This also arose in an experiment with professors.[21] Results showed that professors’ giving was influenced by another’s initial donation amount. But not always. This happened only when the initial donor was revealed to be a member of their own department (peer) or their department chair (leader). Without this information, there was no significant response.

Another study found that showing people data on how their giving compared with others of their same age, education, and region increased their subsequent charitable giving.[22]

A meta-analysis found a similar result. It reported,

“This systematic literature review (35 eligible studies) investigates how individuals’ charitable giving is affected by the giving of others. It [proposes] a new mechanism of decision making in charitable giving through an important psychological construct: similarity.”[23]

If other people give, that’s interesting. If people like me give, that’s powerful.

Experimental results: … make gifts like this

A socially relevant example creates a social norm.[24] This tends to pull giving towards two points:

- Giving at the norm.

- Not giving at all.

Why does this happen? Giving costs. But giving less than the norm still violates the norm. Thus, giving too little doesn’t help reputation. But it still costs something. So, it’s a costly failure. It’s a bad decision.

Giving more than the norm could be acceptable. But the extra cost might be pointless. So, the best options likely narrow to just two: giving at the norm or not giving at all.

These offsetting effects show up in experiments. For example, seeding a transparent donation box with large bills generates fewer, but larger, gifts. Seeding it with coins generates more, but smaller, gifts.[25] Mentioning a large gift by another in an appeal letter raises average gift size. But it lowers the likelihood of giving.[26]

One UK study asked people to donate from a £10 payment. Adding this phrase,

“Did you know that other participants gave £5 and they said that participants such as yourself should give £5?”[27]

had offsetting effects. It increased the share of people giving £5.[28] But it also increased the share who gave nothing.[29] The likelihood of giving amounts other than £5 fell. Again, the social norm pushed giving towards two points: Giving at the norm or not giving at all.

For fundraising, the ideal example is a stretch gift. In one experiment, a phone-a-thon for a public radio station referenced another’s gift. If the example was a bit larger than the donor’s last gift, it tended to increase the donation. If smaller, it tended to decrease the donation.[30]

Examples from major gifts

These experiments show the power of others’ examples in small gift decisions. But major gifts are rare. They’re harder to test. Yet, the same answer emerges.

How can we persuade an ultra-high-net-worth donor to give? By sharing examples of other “people like me.” Josh Birkholz explains,

“You need to be branded as the type of place that [other] ultra-high-net-worth donors give to. How do we do that? One of the key ways is to really go beyond just showing what your organization’s impact on the world is, but to actually demonstrate how specific donors have made a big impact on the world. [emphasis added]”[31]

The key information isn’t just about the charity. It’s about others who are like the donor. It’s about showing that “people like me make gifts like this.”

Similarly, a study of ultra-high-net-worth donors found, “nearly 60% report collaborating with other funders.”[32] In his interviews with mega gift donors, Jerald Panas shares,

“‘People enjoy being part of ‘the club,’ being associated with prominent men and women who are giving to the same cause,’ he says. And my interviewing bears this out. Very few donors enjoy the independent route …”[33]

Examples from people like me work. But what if we don’t already have mega donors to use as examples? There are still ways to provide aspirational examples.

As president of Connecticut College, Claire Gaudiani massively expanded fundraising success. (The college’s endowment more than quadrupled.) Her approach? Sharing donor stories from American history. She recommends,

“Show how the vision of a major donor can transform an institution (Mary Garrett at Johns Hopkins) or an entire city (Ken Dayton in Minneapolis).”[34]

But she shares these stories in a special way. She begins them with a phrase like, “You know, you remind me of [insert historical name].” The donor responds with, “Who is that?” She then shares the story of a donor whose gifts made a major impact.[35] Because of this introduction, this isn’t just an example. For the donor, it becomes an example of someone “like me.”[36]

Conclusion

“People like me make gifts like this.” It’s a powerful message.

- It works in the primal-giving game. (It reveals a reciprocal, sharing community norm.)

- It works in the universal hero story cycle. (It connects the challenge to the donor’s original identity. It validates the promise of a victory. It shows that the victory will deliver an enhanced identity.)

- It works in lab experiments.

- It works in field experiments.

- It works in simple gifts.

- It works in complex planned gifts.

- It works in bequest gifts.

- It works in small dollar gifts.

- It works in major gifts.

And most importantly, it works for people like you. 🙂

Excerpted from the book The Primal Fundraiser: Game Theory and the Natural Origins of Effective Fundraising

Footnotes:

[1] Latin proverb. It has been attributed to, among many, Right Reverend Alfred A. Curtis, D. D., in 1886 as quoted in Nuns, V., & Wilmington, D. (1913). Life and Characteristics of Right Reverend Alfred A. Curtis, DD: Second Bishop of Wilmington. P.J. Kenedy & Sons. p. 104 [2] This is known as the iterated prisoner’s dilemma game. For example, two players both face these payoffs:

where each must choose before knowing what the other will do. See the progression of this approach to modeling the natural origins of giving in the following:

Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1), 35-57;

Axelrod, R., & Hamilton, W. D. (1981). The evolution of cooperation. Science, 211(4489), 1390-1396.;

Boyd, R. (1988). Is the repeated prisoner’s dilemma a good model of reciprocal altruism? Ethology and Sociobiology, 9(2-4), 211-222.

[3] See Chapter 10. The power of community in primal fundraising: I’m not just giving, I’m sharing! [4] These parallel conclusions are not accidental. The monomyth originates in the Jungian hero archetype. Jung explains that an archetype is “an inherited mode of functioning, corresponding to the inborn way in which the chick emerges from the egg, the bird builds its nest, a certain kind of wasp stings the motor ganglion of the caterpillar, and eels find their way to the Bermudas.” Jung, C. (1953-1978). In H. Read, M. Fordham, & G. Adler (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (20 vols). Routledge. Volume XVIII, para. 1228.Another commentator explains, “ethology and Jungian psychology can be viewed as two sides of the same coin: it is as if ethologists have been engaged in an extraverted exploration of the archetype.” Stevens, A. (2001). Jung: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 52.

[5] See Chapter 1. Primal fundraising and subjective similarity: I’m like them! [6] Cason, T. N., & Mui, V. L. (1998). Social influence in the sequential dictator game. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 42(2-3), 248-265; Ebeling, F., Feldhaus, C., & Fendrich, J. (2017). A field experiment on the impact of a prior donor’s social status on subsequent charitable giving. Journal of Economic Psychology, 61, 124-133; Frey, B. S., & Meier, S. (2004). Social comparisons and pro-social behavior: Testing “conditional cooperation” in a field experiment. American Economic Review, 94(5), 1717-1722; Herzog, P. S., & Yang, S. (2018). Social networks and charitable giving: Trusting, doing, asking, and alter primacy. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47(2), 376-394; Lieber, E. M., & Skimmyhorn, W. (2018). Peer effects in financial decision-making. Journal of Public Economics, 163, 37-59; Sasaki, S. (2018). Group size and conformity in charitable giving: Evidence from a donation-based crowdfunding platform in Japan. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2972403 [7] Chen, Y., Harper, F. M., Konstan, J., & Li, S. X. (2010). Social comparisons and contributions to online communities: A field experiment on movielens. American Economic Review, 100(4), 1358-1398. [8] Bryan, J. H., & Test, M. A. (1967). Models and helping: Naturalistic studies in aiding behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6(4), 400-407. [9] Nelson, K. M., Partelow, S., & Schlüter, A. (2019). Nudging tourists to donate for conservation: Experimental evidence on soliciting voluntary contributions for coastal management. Journal of Environmental Management, 237, 30-43. (The opt-in condition was, “I agree to the $X recommended contribution to Lili Eco trust to … offset my environmental impact.” Giving propensity was 55% with the lower suggested amount or 48% with the higher suggested amount. The opt-out condition was, “I do not agree to the $X recommended contribution to Lili Eco trust to … offset my environmental impact.” Giving propensity was 75% with the lower suggested amount or 61% with the higher suggested amount.) [10] Cabinet Office. (2013). Applying behavioural insights to charitable giving. Cabinet Office – Behavioral Insights Team, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/203286/BIT_Charitable_Giving_Paper.pdf ; For another test of this phrase component, see also, James, R. N., III. (2016). Phrasing the charitable bequest inquiry. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(2), 998-1011. [11] James, R. N., III. (2019). Using donor images in marketing complex charitable financial planning instruments: An experimental test with charitable gift annuities. Journal of Personal Finance, 18(1), 65-73. [12] Shang, J., Reed, A., & Croson, R. (2008). Identity congruency effects on donations. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(3), 351-361. [13] Agerström, J., Carlsson, R., Nicklasson, L., & Guntell, L. (2016). Using descriptive social norms to increase charitable giving: The power of local norms. Journal of Economic Psychology, 52, 147-153. [14] Hysenbelli, D., Rubaltelli, E., & Rumiati, R. (2013). Others’ opinions count, but not all of them: Anchoring to ingroup versus outgroup members’ behavior in charitable giving. Judgment & Decision Making, 8(6), 678-690. (Participants were entered into a drawing to win €100 less any amount they had chosen in advance to donate to the charitable cause if they won the drawing.) [15] Id. p. 683 [16] Id. p. 684. Figure 3, HA condition. [17] Shang, J., Reed, A., & Croson, R. (2008). Identity congruency effects on donations. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(3), 351-361. [18] Bennett, C. M., Kim, H., & Loken, B. (2013). Corporate sponsorships may hurt nonprofits: Understanding their effects on charitable giving. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(3), 288-300. (Learning of corporate sponsorship can reduce willingness to donate unless the donor has a high level of identification with the company. The authors write, “Therefore, unless prospective donors feel sufficiently attached to corporate donors (so as to create similarity or identification with the donor, which can instill the belief that helping is the norm), publicizing corporate sponsors can have a negative effect, resulting in decreased willingness to support a nonprofit among prospective individual donors.” p. 290.); Drouvelis, M., & Marx, B. M. (2021). Dimensions of donation preferences: the structure of peer and income effects. Experimental Economics, 24(1), 274-302. p. 276; Herzog, P. S., Harris, C. T., Morimoto, S. A., & Peifer, J. L. (2019). Understanding the social science effect: An intervention in life course generosity. American Behavioral Scientist, 63(14), 1885-1909; Tian, Y., & Konrath, S. (2021). The effects of similarity on charitable giving in donor–donor dyads: A systematic literature review. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32, 316-339. p. 316; Zhang, J., & Xie, H. (2019). Hierarchy leadership and social distance in charitable giving. Southern Economic Journal, 86(2), 433-458. [19] Fishbach, A., Henderson, M. D., & Koo, M. (2011). Pursuing goals with others: Group identification and motivation resulting from things done versus things left undone. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 140(3), 520-534. [20] Drouvelis, M., & Marx, B. M. (2021). Dimensions of donation preferences: the structure of peer and income effects. Experimental Economics, 24(1), 274-302. p. 276. [21] Zhang, J., & Xie, H. (2019). Hierarchy leadership and social distance in charitable giving. Southern Economic Journal, 86(2), 433-458. [22] Herzog, P. S., Harris, C. T., Morimoto, S. A., & Peifer, J. L. (2019). Understanding the social science effect: An intervention in life course generosity. American Behavioral Scientist, 63(14), 1885-1909. [23] Tian, Y., & Konrath, S. (2021). The effects of similarity on charitable giving in donor–donor dyads: A systematic literature review. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32, 316-339. p. 316. [24] In general, as people’s expectations that others are giving grows, so does their own giving. For example, one study used real donation data on a large crowdfunding platform in Japan. The researchers report, “We find a donor likely imitates the donation amount that many others have selected … The likelihood increases when more of the others have given the similar amount … This result supports the notion that a donor’s conformity behavior is more likely to occur when a greater proportion of other donors give a similar amount.” Sasaki, S. (2019). Majority size and conformity behavior in charitable giving: Field evidence from a donation-based crowdfunding platform in Japan. Journal of Economic Psychology, 70, 36-51.Similarly, in another study, the answer to the question “How interested do you think others are in giving to women’s and girls’ causes?” largely predicted the person’s own intentions to give to these causes. Mesch, D., Dwyer, P., Sherrin, S., Osili, U., Bergdoll, J., Pactor, A., & Ackerman, J. (2018). Encouraging giving to women’s and girls’ causes: The role of social norms. IUPUI Women’s Philanthropy Institute. Figure 1. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/handle/1805/17949

However, a social norm does not have to reflect majority behavior. A person can identify with a smaller group, rather than the majority. For example, in the previous study this phrase reduced giving to these causes: “Less than half of donors give to women’s and girls’ charities.” But the negative impact disappeared when adding, “but the number of donors is getting bigger and bigger each year.” This addition made the non-majority behavior more attractive.

[25] Martin, R., & Randal, J. (2008). How is donation behaviour affected by the donations of others? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 67(1), 228-238. [26] Jackson, K. (2016). The effect of social information on giving from lapsed donors: Evidence from a field experiment. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(2), 920-940. [27] van Teunenbroek, C., Bekkers, R., & Beersma, B. (2021). They ought to do it too: Understanding effects of social information on donation behavior and mood. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 18(2), 229-253. p. 231. [28] Id. p. 240. Table 3. (The share of participants giving £5 was 26% in the control group and 37% in the group exposed to the message.) [29] Id. (The share of participants giving nothing was 61% in the control group and 68% in the group exposed to the message.) [30] Croson, R., & Shang, J. Y. (2008). The impact of downward social information on contribution decisions. Experimental Economics, 11(3), 221-233. [31] Birkholz, J. (2019). BWF live fundraising show: 2019 – 12 things for consideration. [Video]. [34:00], https://m.facebook.com/BentzWhaleyFlessner/videos/bwf-live-fundraising-show-2019-twelve-things-for-considerationjosh-birkholz-prin/279456562721405/ [32] Tripp, K. D. & Cardone, R. (2017). Going beyond giving: Perspectives on the philanthropic practices of high and ultra-high net worth donors. The Philanthropy Workshop. p. 12. https://www.ncfp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Going-Beyond-Giving.pdf [33] Panas, J. (2005). Mega gifts: Who gives them, who gets them (2nd ed.). Emerson & Church Publishers. p. 34. [34] Gaudiani, C. (2012). How to use the greater good. [Website].http://www.clairegaudiani.com/Writings/Pages/HowToUseGreaterGood.aspx

now archive only at https://web.archive.org/web/20170923063952/http://www.clairegaudiani.com/Writings/Pages/HowToUseGreaterGood.aspx

Her book, The Greater Good, is a collection of heroically-framed donor stories from American history. She recommends that fundraisers’ use the book in this way:

“Need a GREAT STORY to illustrate your message about the importance of philanthropy? Tell a group of volunteers/smaller donors about the success of the Mother’s March of Dimes or the creation of Provident Hospital. Show how the vision of a major donor can transform an institution (Mary Garrett at Johns Hopkins) or an entire city (Ken Dayton in Minneapolis). Demonstrate how risk-taking is essential for real social and economic progress (Guggenheim support to the aviation industry). Connect your philanthropic effort with the American entrepreneurial spirit (John Winthrop’s Sermon on the “Arabella”)”

[35] Author’s notes from Guadiani, C. (2018, October 17). Luncheon keynote. [Presentation]. Charitable Gift Planners Conference, Las Vegas, NV. [36] One study finds this identification with such “moral and civic virtue exemplars,” to be a powerful predictor of pro-social action (giving and volunteering) among adolescents as well. The researchers explain, “adolescents who have made a habit of social action (having participated in the previous 12 months and intending to participate again in future) are more likely to … identify themselves more closely with moral and civic virtue exemplars, and say that other people who know them also think they are more like the moral and civic virtue exemplars”. Taylor-Collins, E., Harrison, T., Thoma, S. J., & Moller, F. (2019). A habit of social action: Understanding the factors associated with adolescents who have made a habit of helping others. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(1), 98-114. p. 109.

Related Resources:

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- How transactional donor relationships kill generosity

- Dr. James explains the power of giving: why leading with a gift always wins