Story works

In fundraising, story is powerful. Story works better than formal descriptions. Story works better than facts and figures. Simply, story works better than non-story.

But for an effective fundraising story, we need something more. It’s not enough to tell a story. We need to tell the donor’s story.

The donor’s story works

A compelling ask includes,

When does a story become the donor’s story? This happens when the donor identifies with its characters and values. Fundraising starts with identity. Donors identify with characters they feel are like them.

Screenwriter Robert McKee explains it this way:

“Empathetic means ‘like me.’”[1]

In brain research, donations involve taking another’s perspective.[2] They also involve empathy for the other’s situation.[3] Both steps are easier when donors feel the other person is like them.

This feeling of similarity is powerful in fundraising. To understand why, we need to go back. Way back. All the way back to natural origins.

Natural origins

In 1964, W. D. Hamilton presented a genetic model for giving.[4] Giving doesn’t help the donor. But it can help the donor’s genes. Giving is genetically helpful when,

My Cost < (Their Benefit X Our Similarity).

The math is easy. More benefit means more giving. Thus, need or impact matters. But so does similarity.

This simple model matches some findings. Similarity in

- Behavior

- Location, or

- Appearance

correlates with genetic similarity.[5] Sharing these factors also increases cooperation and altruistic sharing.[6]

People often give more to those who are like them in some way. In experiments, giving increases when the donor and recipient share

- Political views

- Religious views

- Sports-team loyalty, or even

- Music preferences.[7]

Similarity is subjective

Hamilton’s math is simple. But people are complex. A specific similarity with another is an objective fact. But its importance is not objective. Its importance is subjective.

Not every similarity counts. It must trigger a feeling that the other person is “like me.” It must trigger identification. Important similarities are identity-defining similarities.

Suppose a giver and receiver share a likeness. They might both be Catholic. Or from Ohio. Or Hispanic. If a donor identifies with the factor, emphasizing it will help. Otherwise, it won’t. That’s why some similarities matter and others don’t.

In one experiment, people could donate to rebuild after a hurricane.[8] But different people saw different photos of damage. The victims in the photos were white, or black, or obscured. Which pictures worked better? It depended.

Potential donors were asked, “How close do you feel to your ethnic or racial group?” Those answering, “very close” or “close,” gave more when the pictured victims matched their own race. For those answering, “not very close” or “not close at all,” the result reversed. They gave more when the victims did not match their own race.

Race mattered. But identity determined how it mattered. Objective similarity mattered. But subjective feelings determined how it mattered.[9]

Similarity with charities

Similarities with a beneficiary can make a difference. But in fundraising, the donor doesn’t give directly to a beneficiary. The donor gives to a charity.

This creates another chance for shared identity. The donor can still identify with a beneficiary. But he can also identify with the charity and its agents.[10]

For example, a donor might give to famine relief through his church. But he might never have given directly to a famine relief charity. The famine victims might be identical. The impact might be identical. But the charity is different. Sharing identity with the charity can motivate a gift.

A donor can also identify with the fundraiser. Sharing similarities can help. In experiments, people are more compliant if the requester shares

- The same birthday

- Fingerprint similarities, or

- The same first name.[11]

One study examined 27 years of major gift proposals at a major research university.[12] When female major gift prospects were solicited by female fundraisers, they

- Were more likely to give,

- Gave larger amounts, and

- Were more likely to make subsequent gifts.

Another study looked at a university’s fundraising phone calls. Alumni were more likely to give to student callers who shared their same

- Field of study [13]

- First name, or even

- First letter of their first name.[14]

This also happened when the alumnus’s name started with the same letter as the university’s name.

Another study found a similar result. It asked for donations for an education project. If the project was led by a teacher with the donor’s first name, giving doubled.[15]

The importance of name matching might seem odd. But one’s name is central to one’s identity. In fundraising, identity-defining similarities are powerful.

Fundraising and subjective similarities

Identity-defining similarity makes giving attractive. Similarities can be shared with beneficiaries or charity personnel. But this shared identity is not fixed. A fundraiser can influence it. She[16] can,

- Reference and remind donors of similarities.

- Shape perceived similarities through Socratic inquiry.

- Build perceived similarities through donor experiences.

- Suggest giving options that match with identity-defining similarities.

Some similarities are obvious. But the real power comes from similarities that matter to the donor. These connect with the donor’s identity-defining characteristics.

How can a fundraiser discover these? By listening. Powerful fundraising begins by asking questions and listening. Appreciative inquiry can uncover the donor’s life story and values. These reveal the donor’s identity-defining traits. They show the similarities that matter to the donor.

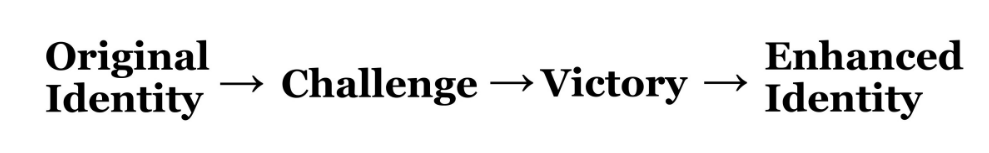

Armed with this information, the fundraiser can match the giving challenge with the donor’s identity. A gift can support specific projects. It can help specific people. It can advance specific values. This can link the first two steps in the journey:

A fundraiser can uncover these identity-defining factors. But she can do more. She can influence them. Asking what’s important to the donor changes attitudes. It highlights the importance of these issues. In experiments, asking donors about the importance of causes or projects increases support.[17] Asking donors to recall life story connections to a cause does the same.[18] These Socratic processes change donor attitudes.

Donor experiences can also build shared identity. Events can create a sense of shared group membership. They can enhance feelings of similarity. Marketing, too, can emphasize shared identity. Any experience that makes the donor think, “I’m like them” is powerful.

Summary

Similarities matter. They matter for the beneficiary. They matter for the charity. Ultimately, helping people or organizations like “us” is compelling. But this “us” is not set in stone. The donor subjectively defines this “us” group. However the donor defines it, being part of “us” is powerful.

Footnotes:

[1] Mckee, R. (1997). Story: Substance, structure, style and the principles of screenwriting. ReganBooks. p. 141. [2] Hare, T. A., Camerer, C. F., Knoepfle, D. T., O’Doherty, J. P., & Rangel, A. (2010). Value computations in ventral medial prefrontal cortex during charitable decision making incorporate input from regions involved in social cognition. Journal of Neuroscience, 30(2), 583-590. [3] Id. [4] Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7(1), 17-52. [5] Rushton, J. P. (1989). Genetic similarity, human altruism, and group selection. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(3), 503-518. [6] Id. [7] Ben-Ner, A., McCall, B. P., Stephane, M., & Wang, H. (2009). Identity and in-group/out-group differentiation in work and giving behaviors: Experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 72(1), 153-170. [8] Fong, C. M., & Luttmer, E. F. (2009). What determines giving to Hurricane Katrina victims? Experimental evidence on racial group loyalty. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(2), 64-87. [9] See also, Carboni, J. L., & Eikenberry, A. M. (2021). Do giving circles democratize philanthropy? Donor identity and giving to historically marginalized groups. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32, 247-256. p. 247. (“Findings show giving circle members and those not in giving circles are both more likely to give to a shared identity group – related to race, gender, and gender identity – leading to bonding social capital. However, giving circle members are more likely than those not in giving circles to give to groups that do not share their identity, suggesting giving circles also encourage bridging social capital.”) [10] One study of donors to a Division I athletic department found that organizational identification mediated the effects of other marketing programs on donations. The researchers explained,“… this study found that fans who were satisfied with [the athletic department’s philanthropic Corporate Social Responsibility] initiatives on an athletic department website were more likely to be identified with the athletic department. In turn, a fan’s identification with the athletic department affected his or her online donation intentions to the athletic department.” (p. 610)

Hwang, G., Kihl, L. A., & Inoue, Y. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and college sports fans’ online donations. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 21(4), 597-616.

[11] Burger, J. M., Messian, N., Patel, S., del Prado, A., & Anderson, C. (2004). What a coincidence! The effects of incidental similarity on compliance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(1), 35-43. [12] Adams, C. C. (2017). Gender congruence and philanthropic behavior: A critical quantitative approach to charitable giving practices. [Dissertation]. University of Missouri-Columbia. https://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/handle/10355/62238 [13] Bekkers, R. (2010). George gives to geology Jane: The name letter effect and incidental similarity cues in fundraising. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 15(2), 172-180. [14] This difference was 40.9% vs. 19.5% [15] Munz, K., Jung, M., & Alter, A. (2017). Charitable giving to teachers with the same name: An implicit egotism field experiment. ACR North American Advances, 45. http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/v45/acr_vol45_1024370.pdf [16] As a convention for clarity and variety, throughout this series the donor/hero is referred to with “he/him/his” and the fundraiser/sage is referred to with “she/her/hers.” Of course, any role can be played by any gender. [17] James, R. N., III. (2018). Increasing charitable donation intentions with preliminary importance ratings. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 15(3), 393-411. [18] James, R. N., III. (2015). The family tribute in charitable bequest giving: An experimental test of the effect of reminders on giving intentions. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 26(1), 73-89; James, R. N., III. (2016). Phrasing the charitable bequest inquiry. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(2), 998-1011.

Related Resources:

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- The Importance of Asking Permission to Ask More Questions

- Finally, the questions you should ask that have been proven to lead to gifts from wealth