Monomyth steps

The “one big thing” in fundraising is always the same: Advance the donor’s hero story.

The universal hero story, called the monomyth, includes specific steps. The hero,

- Begins in the ordinary world

- Is faced with a challenge (the call to adventure)

- Rejects then accepts the call and enters the new world

- Undergoes ordeals and overcomes an enemy

- Gains a reward or transformation, and

- Returns to the place of beginning with a gift to improve that world.

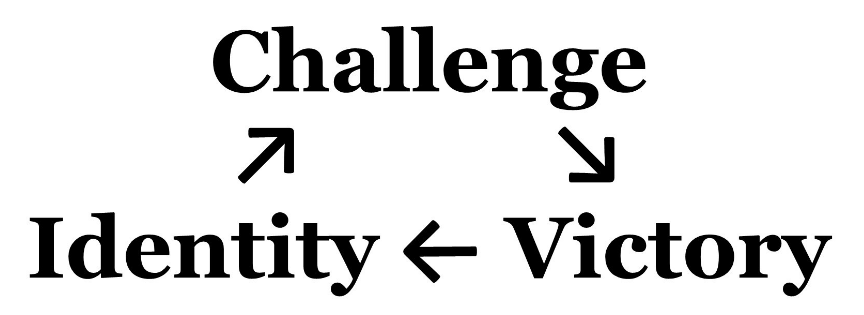

This hero story progresses through

![A box and arrow diagram where "Original Identity" links to "Challenge" links to "Victory" links to "Enhanced Identity". Below "Original identity" is [1]. Below "Challenge" is [2,3,4]. Below "Victory" is [4,5]. Below "Enhanced Identity" is [5,6].](https://mssitesdev.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2022/11/Arrow-diagram-where-Original-Identity-links-to-Challenge-links-to-Victory-links-to-Enhanced-Identity.png)

In three words, the monomyth cycle is:[1]

The compelling donor experience will include each step. The compelling fundraising challenge will make each link.

Narrative steps

This is a specific story. It has specific steps. But it’s just one example of the usual steps in story. All story uses a narrative arc. This typically includes

- Backstory

- Setting

- Inciting incident

- Climax, and

- Resolution.

Advancing any story means progressing through this narrative arc. In the donor’s hero story, each step has a specific purpose:

- The backstory connects the donor’s original identity with the cause, organization, beneficiaries, or project.

- The setting prepares the donor for the challenge. It promotes personal and social norms supporting a heroic response.

- The inciting incident is the challenge. It forces a choice with the promise of victory in response to a crisis (threat or opportunity).

- The climax delivers the promised victory.

- The resolution confirms the donor’s enhanced identity resulting from the victory.

The donor’s hero story is a story. It’s a specific application of the narrative arc.

Why story?

Why is this series so focused on story? It seems like a lot to go through. I mean, that’s a lot of steps. Why not just learn the best phrase to make the ask and get on with the asking? Or why not just collect a list of fundraising tips and tricks?

There’s a reason. Story is powerful. Story is how humans are wired. Story works. Focusing on one phrase or one step is interesting, but these don’t work by themselves. They work only as part of a story.

What are we doing, anyway?

What’s the difference between good and bad fundraising? That’s easy, right? Good fundraising brings in big money. Bad fundraising doesn’t.

The problem with this definition becomes obvious when we apply it to other jobs. A good football player brings in big money. So does a good lawyer. Or a good comedian. Money is a result of being good at these jobs. But it’s not a definition for being good at any of them.

Why do these top people get big money? Because they provide value. We live in a choice economy, not a command economy. Big money comes by providing big value. Other professions provide value in different ways. What about fundraising?

A charity can provide value to many people in many ways. But fundraising provides value to the donor in just one way: identity enhancement. This identity might be internal, private, and transcendent.[2] It might be external, public, and commercial. But identity enhancement is always the ultimate benefit to the donor.

Story works for the donor

The right goal is to provide value to the donor. Fundraising provides this value through an enhanced identity. That’s the right goal. What’s the right process? It starts with story. Story is natural. It’s memorable. It’s compelling.

One study analyzed over 5,000 cancer-related campaigns on GoFundMe.[3] Those using a story metaphor, either a journey or a battle, attracted 15% more donors and 11% larger donations.

Story works. What works even better is deeply embedded, primal, archetypal story. Among these archetypal stories, one is best suited to compel major, transformational gifts. It’s the hero story. The right process to deliver enhanced identity is this: Advance the donor’s hero story. When the donor experience delivers this narrative arc, it provides real value.

In fundraising, story works to motivate the donor. But it also works for the fundraiser.

Story works for the fundraiser

Story works. It doesn’t work only for the donor. It also works for the fundraiser. Ask a typical person to explain these steps:

- Identification

- Cultivation

- Solicitation

- Recognition

- Stewardship

You’ll likely get a blank stare. These insider terms aren’t natural. They aren’t memorable. They aren’t intuitive.

But people intuitively understand story. We can convert these steps into story.

- Backstory [Identification]

- Setting [Cultivation]

- Inciting incident [Solicitation]

- Climax [Recognition]

- Resolution [Stewardship]

The steps may be the same, but now they’re made into a story. This helps because we know, intuitively, when a story works. We also know when it doesn’t. Read any novel. Watch any movie. You’ll be able to answer these questions:

- Did this backstory and setting make me care about the characters?

- Did the inciting incident present a compelling choice?

- Did the resulting journey lead to a successful climax?

- Did the story end with a satisfying resolution?

This intuitive guidance disappears when we instead use technical words.

- How is your identification and cultivation?

- How is your solicitation?

- How is your recognition?

- How is your stewardship?

Now, we’ve lost the intuition of what we’re trying to accomplish. These words aren’t wrong, but they have little qualitative feeling. This can cause problems. It can lead to a superficial, check-the-box approach. It can even lead to skipping steps entirely.

Including each step makes the story complete. This also helps appeal to the widest range of donors. Some may be more focused on the victory step (impact on others). Some may be more compelled by the enhanced identity step (a form of personal benefit). In experiments, these two message types appealed to different donors[4] in different circumstances.[5] But a complete story includes both elements. It connects with more donors.

Story is memorable

Getting a list of facts, figures, tips, and tactics is great. We can understand. We can nod our heads. But when we get up the next morning, how much do we remember? Humans remember through stories.

In memory competitions, people memorize a sheet of random numbers. How do they do this? They do it by converting the numbers into stories.

In advance, they connect each two-digit sequence with a person, an action, and an object.[6] That makes every six-digit sequence a unique story image. A page of numbers becomes a journey through these story images. Humans can’t remember a page of numbers by itself. But they can remember a set of stories.

Ancient humans looked up at an endless array of stars. Their response? Turn these countless dots into story characters. This is Orion the hunter. This is Leo the Lion or Taurus the Bull. Now they could remember and reference each dot with ease.

Character works better than commands

Story is easier to remember. It’s also easier to execute. In fundraising, story works better than a list of tips and tactics. This is because character works better than a set of commands.

Suppose we told a singer to perform a song as Elvis. Instantly, the singer knows,

- How to sound

- How to move

- What to wear, and

- What phrases to say.

But what if the singer had never heard of Elvis? How many instructions would this take? A lot! And even then, the performance still wouldn’t work as well.

Advancing the donor’s hero story gives the fundraiser an intuitive character role.[7] The guiding sage challenges the prospective hero with a choice. This is an archetypal character. Your favorite version might be Obi-Wan Kenobi, Minerva McGonagall, Gandalf the Grey, Morpheus, Mr. Miyagi, or someone else. Imagining a character provides better intuitive guidance than a set of rules. It’s not just a change in what we are doing. It’s a change in who we are being.[8] It’s an existential change.[9]

Once a fundraiser is being a character, adapting to new situations becomes easier. Is it OK to disappear after making the compelling ask? Obi-Wan Kenobi wouldn’t. Should we guide the donor to another specialist advisor? Obi-Wan sent Luke to Yoda. Morpheus sent Neo to the Oracle. We know what actions fit because we know the character.

Conclusion

Fundraising isn’t about knowing the right term. It’s not about passing a quiz. It’s about executing in the real world. Execution can involve using specific phrases and asking specific questions. But the questions don’t work unless we know where we’re going.

This is where story becomes powerful. Story makes effective fundraising natural. It makes it memorable. It makes it intuitive.

Ultimately, effective fundraising is about delivering value. Story can do that. It not only helps get the big gift. It also helps deliver a donor experience worth that gift.

Footnotes:

[1] Campbell uses a three-step circular illustration with this description:“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Campbell, J. (1949/2004). The hero with a thousand faces (commemorative ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 28.

I label these steps as follows:

The beginning point of “the world of common day” is “original identity.”

“Venturing forth into a region of supernatural wonder” is “challenge.”

“Fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won” is “victory.”

“The hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man” is “enhanced identity.”

I apply this both to a scenario where the charitable gift serves as part of the final step in the heroic life story and where the gift request itself constitutes the challenge that promises a victory delivering enhanced identity.

[2] This discussion will focus on identity enhancement in its most basic form. This can be as simple as, for example, “I feel better about myself after I give.” However, this actually touches on the substantially more complex journey of individuation. Individuation “denotes the process by which a person becomes a psychological ‘in-dividual,’ that is, a separate, indivisible unity or ‘whole.’ Jung, C. G. (1990). The archetypes and the collective unconscious. In H. Read, M. Fordham & G. Adler (Eds.), R.F.C. Hull (Trans.), The collected works of C. G. Jung. Vol 9 (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 275. [3] This study examined data from more than 5,000 Go-FundMe cancer-related campaigns. It found, “The results suggest that campaigns that use at least one metaphor family—regardless of whether it is a journey or battle—attract about 15% more donors and about 11% larger average donations.” (p. 2571) Liebscher, A., Trott, S., & Bergen, B. (2020). Effects of battle and journey metaphors on charitable donations for cancer patients. Proceedings for the 42nd Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society (July 29- August 1, 2020), online. https://cogsci.mindmodeling.org/2020/papers/0613/0613.pdf [4] Different people respond more strongly to messages of impact [victory] and benefit [enhanced identity]. One study reported this: “In the self-interest treatment it was stated that ‘[r]esearch by psychologists shows that donating money to charity increases the happiness and wellbeing of the giver’. In the altruism treatment it was stated that ‘[a]ny donation you make will improve the happiness and wellbeing of an African family’ … materialists in the self-interest treatment give more than materialists in the pure altruism treatment; for non-materialists the reverse is true.” Fielding, D., Knowles, S., & Robertson, K. (2020). Materialists and altruists in a charitable donation experiment. Oxford Economic Papers, 72(1), 216-234. p. 221-222. [5] These preferences for one of the two story elements (victory or enhanced identity) differ not only across people, but under different circumstances. In other words, these preferences are not fixed. For example, inducing feelings of social exclusion makes people more interested in benefitting others (i.e., becoming more valuable to others), rather than themselves. Inducing feelings of social exclusion (by playing a multi-player video game of catch where the participant was gradually excluded) decreased the persuasiveness rating for imagining how a donation would “Bring more fulfillment to your life” and increased the rating for “Enhance the lives of those suffering from hunger.” Inducing feelings of social exclusion (by having participants recall life events where they experienced social exclusion) slightly decreased giving to cancer research advertisement with headlines of “Save your life” and “Protect your future” but doubled giving to those with headlines of “Save people’s lives” and “Protect the well-being of others.” This also decreased giving intentions for “Make yourself feed good by donating!” but increased giving intentions for “Bring clean water to people in need by donating!” Baek, T. H., Yoon, S., Kim, S., & Kim, Y. (2019). Social exclusion influences on the effectiveness of altruistic versus egoistic appeals in charitable advertising. Marketing Letters, 30(1), 75-90.Thus, different people (Fielding, et al, 2000) in different circumstances (Baek, et al., 2019) may be more attracted to the impact [“victory”] portion of the story or the self-benefit [“enhanced identity”] portion of the story. Telling a complete story [identity → challenge → victory → enhanced identity] ensures that both portions are included.

Fielding, D., Knowles, S., & Robertson, K. (2020). Materialists and altruists in a charitable donation experiment. Oxford Economic Papers, 72(1), 216-234.

“I suggest that an explanatory framework for understanding the “major giving” interaction will need the following characteristics:

1. Be explanatory rather than simply being a list of tactics or techniques for success;

2. Be consistent with findings of research;

3. Be comprehensible and recognisable, as well as useful to the actors – fundraisers, philanthropists, advisers and (in the case of fundraisers) their managers and leaders; and

4. Be compatible with the complexity of processes that may be at work in the philanthropic interaction”

Mc Loughlin, J. (2017). Advantage, meaning, and pleasure: Reframing the interaction between major‐gift fundraisers and philanthropists. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 22(4), e1600. p. 1-2.

The fundraiser’s role as the guiding sage within the donor’s hero story (monomyth) context provides an intuitive framework that meets each of these tests.

Related Resources:

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- At last, the one big thing every fundraiser needs to know to be successful

- The 3 Key Elements of a Good Fundraising Story