We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

How gratitude completes the donor hero story

“In myths the hero is the one who conquers the dragon, not the one who is devoured by it.”

– Carl Jung[1]

Monomyth resolution

In the universal hero story, the hero wins. The dragon is slain. The victory is won. But the story doesn’t end there. One step remains: The hero returns.[2]

Joseph Campbell writes, “the adventurer still must return with his life-transmitting trophy. The full round, the norm of the monomyth, requires the hero should now begin the labour of bringing the runes of wisdom, the Golden Fleece, or his sleeping princess, back into the kingdom of humanity, where the boon may redound to the renewing of the community …”[3]

The story started in the hero’s ordinary world. This shows his backstory. It shows his people and values. These are his sources of identity. The story ends in the same world. The hero returns.

But he returns as a different person. He started as a seemingly ordinary person in his ordinary world. He returns as a hero. He is

- Meaningfully victorious, and

- Personally transformed.

The final step in the hero story confirms this heroic status. It confirms his new identity. In the narrative arc, this is the story’s resolution.

Monomyth resolution: Meaningfully victorious

The hero wins a victory. The final step confirms its meaning. It is meaningful because it benefits the hero’s community. It benefits his people and values. It enhances his sources of identity.

This confirmation can be internal. The hero can observe the impact of his victory. He can see the transformation to his original world.

This confirmation can also be external. Public acclaim for the victory confirms its meaningfulness. Gratitude affirms its impact.

Monomyth resolution: Personally transformed

The hero is also personally transformed. He is not the same person he was before. He has grown. His identity has been enhanced. This final step confirms it.

This confirmation can be internal. The return to his original world recalls his original self. This old image contrasts with his new one. It contrasts with his now-transformed self. This comparison highlights the personal transformation.

The confirmation can also be external. The hero is honored. Public admiration confirms his altered identity. Gratitude affirms his heroic transformation.

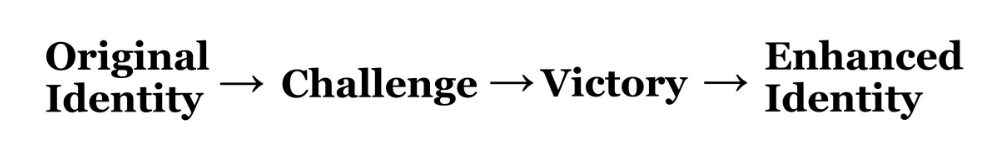

The hero’s journey is an identity enhancement process.[4] It progresses through [5]

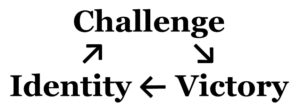

Or simply, [6]

The final step confirms the hero’s enhanced identity.[7] It verifies his heroic status. He has become a

- Meaningfully victorious, and

- Personally transformed hero.

Monomyth resolution: Let’s go to the movies

This isn’t just academic theory. The highest-grossing movie franchises are hero stories. The final scene often provides this resolution. It confirms the hero’s enhanced identity.

This occurs in the original Star Wars film. The ending scene is one of public gratitude and honor. The heroes receive medals at a formal ceremony. Hundreds stand at attention. This also occurs in the final Lord of the Rings film. The ending scene is nearly identical. A massive audience bows to the heroes at a formal ceremony. Their transformation into heroes is publicly confirmed.

In The Hobbit, the final scene is different. Here, the confirmation is private. Bilbo returns to his home and grows old. Then, he reflects on the memories of the adventure. (He has been changed.) He holds the ring: the spoils of victory. (He has been victorious.) By holding the ring, he protects the community. (The victory is meaningful.)

The scene ends with the arrival of the guiding-sage Gandalf. Gandalf can recall and confirm this heroic journey. He can do so now, privately. He can also do so for future generations, publicly. (Wizards live a very long time!)

Neo returns to the matrix in the final scene. This is the original world where the film began. But now he is transformed. He has acquired previously unimagined powers. These were won in his journey. This “trophy” now becomes a gift. It’s a gift to benefit his original world. His closing words confirm it. He tells the defeated villain, “I’m going to show these people what you don’t want them to see. I’m going to show them a world … where anything is possible.”[8]

These ending scenes verify the heroic status. The main character returns to the ordinary world. But he returns as a

- Meaningfully victorious, and

- Personally transformed hero.

Fundraising resolution

Hero stories from both mythic tradition and modern film agree. The final story step confirms the hero’s new status. This is the story’s resolution.

What about fundraising? Personal transformation might seem like a lofty goal for a donation. A meaningful victory that enhances identity might too. But these are just extreme versions of a simple idea.

The final step in the donation experience is a confirmation. It confirms the donor’s positive identity. It confirms a positive philanthropic identity. This can come from two sources:

- The giving of the gift

The identity message is this: “I am a

- Generous

- Faithful

- Prosperous

- Committed

member of the community.”

- The impact of the gift

The identity message is this: “I am an

- Effective

- Successful

- Victorious

- Valuable

member of the community.”

The confirmation can be internal. Observing (or being reminded of) one’s own giving or impact works. It causes “self-signaling.”[9] It helps the donor internally confirm a positive identity. Acknowledging the gift can trigger this. So can reporting the gift’s impact.

The confirmation can also be external. This comes from gratitude and publicity. Gratitude comes from beneficiaries or their representatives. It confirms the donor’s positive identity. Effective publicity causes others to confirm this as well. In either case, outsiders confirm the donor’s positive identity.

Gratitude for the act of giving

An effective “thank you” can work on two levels. First, it can recognize the giving of the gift. It can confirm that the donor accepted the challenge. But great gratitude goes further. It doesn’t just acknowledge the gift. It confirms the donor’s positive identity resulting from the act of giving. The donor is generous, faithful, and sacrificial. The donor is a committed member of the community.

This gratitude can start right away. It can start even before (or without)[10] any impact. This gratitude is not about impact. It’s about the act of giving the gift.

Gratitude for the impact of giving

Gratitude can do more. It can also confirm the impact of the gift. But great gratitude goes even further. It confirms the donor’s positive identity resulting from the impact of the gift. The donor is effective, successful, and victorious. The donor is a valuable member of the community.

Great gratitude can do a lot. It can confirm the full donor-hero story. First, it can confirm that the donor accepted a heroic challenge. This comes from the making of the gift. (It was a sacrificial gift in a moment of crisis or opportunity.) Second, gratitude can confirm that the donor won a meaningful victory. This comes from the impact of the gift. (It protected the donor’s people and values.) In both ways, gratitude can confirm the donor’s enhanced identity. (The donor is a generous, victorious hero.)

Gratitude: Research

Effective gratitude delivers value to the donor. This encourages the next gift. It also confirms a positive philanthropic identity. This helps too. Confirming this identity changes behavior. Afterward, people’s actions will tend to match this identity. This also encourages the next gift.

Gratitude encourages the next gift. Research shows this.[11] One study examined 70,441 donations on a charitable crowdfunding platform. It found that a “successful donation result and ‘Thank-You’ feedback from fundraisers can significantly decrease [donors’] attrition rate.” [12]

Gratitude also encourages fulfilling a gift pledge. Another experiment found, “If expressions of gratitude are then targeted to individuals who select into pledges, reneging can be significantly reduced and contributions significantly increased.”[13]

Gratitude quality: Research

A “thank you” can work. But the effects depend on the content of the “thank you.”[14] One experiment varied this message. Students called donors to a university’s fundraising campaign. The script included details on the campaign goals and impact.[15] It included a personal “thank you.” A second version was almost the same. But it had one difference. It added two sentences: “You went out of your way to support us, and we want you to know how much we appreciate you. Basically, we think you’re great.”[16]

This addition nearly doubled the likelihood of later gifts.[17] The added lines did something special. They specifically confirmed the donor’s positive identity.

Conclusion

Great gratitude includes gratitude for a gift (accepted a heroic challenge). It includes gratitude for an impact (won a heroic victory). But ultimately, it’s not just gratitude for what the donor did. It’s gratitude for who the donor is. It’s not just transaction gratitude (“You did a good thing”). It’s relationship gratitude (“You are a good person”). It’s gratitude that confirms an enhanced identity.

Great gratitude confirms the full donor-hero story. It confirms an accepted challenge. It confirms a meaningful victory. It confirms an enhanced identity. It’s the “resolution” step in the donor’s hero story.

Footnotes:

[1] Jung, C. (2014). The conjuction. In M. Adler, H. Fordham, and W. McGuire (Eds.), The collected works of C. G. Jung (2nd ed.) (20 vols). Princeton University Press. Volume VIII, para. 414.

[2] This nóstos or “homecoming” pattern is myriad in epic Greek literature, beginning with Homer’s Odyssey. See Alexopoulou, M. (2003). The homecoming (nóstos) pattern in Greek tragedy. [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Glasgow.

[3] Campbell, J. (1949/2004). The hero with a thousand faces (commemorative ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 193.

[4] For example, “this hero’s journey corresponds to a process of individual development from a disjointed sense of identity to a consolidated identity, when the individual acquires a clear sense of aspiration in life” Golban, T. (2014). Rewriting the hero and the quest: myth and monomyth in Captain Corelli’s Mandolin by Louis de Bernières. Peter Lang GmbH. p. 34.

For an argument that the protagonist of the Bildungsroman – coming of age story or “the novel of identity formation” – is “at the same time the hero of the monomyth” see Karabakir, T., & Golban, P. (2019). The Bildungsroman as Monomythic fictional discourse: Identity formation and assertion in great expectations. Humanitas: International Journal of Social Sciences, 7(14), 318-336.

See also discussions in Elenbaas, J. D. (2016). Excavating the mythic mind: Origins, collapse, and reconstruction of personal myth on the journey toward individuation. [Ph.D. Dissertation]. Pacifica Graduate Institute; Gerhold, C. (2011). The hero’s journey through adolescence: A Jungian archetypal analysis of “Harry Potter”. [Ph.D. Dissertation]. The Chicago School of Professional Psychology.

[5] The monomyth includes specific steps. The hero,

- Begins in the ordinary world

- Is faced with a challenge (the call to adventure)

- Rejects then accepts the call and enters the new world

- Undergoes ordeals and overcomes an enemy

- Gains a reward or transformation

- Returns to the place of beginning with a gift to improve that world

This hero story progresses through

Original Identity [1] → Challenge [2, 3, 4] → Victory [4, 5] → Enhanced Identity [5, 6]

[6] Campbell uses a three-step circular illustration with this description:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Campbell, J. (1949/2004). The hero with a thousand faces (commemorative ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 28.

I label these steps as follows:

The beginning point of “the world of common day” is “original identity.”

“Venturing forth into a region of supernatural wonder” is “challenge.”

“Fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won” is “victory.”

“the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man” is “enhanced identity.”

I apply this both to a scenario where the charitable gift serves as part of the final step in the heroic life story and where the gift request itself constitutes the challenge that promises a victory delivering enhanced identity.

[7] This enhanced identity can be as simple as external prestige or an internal “warm glow.” However, it also touches on Jung’s more nuanced journey of individuation.

[8] Wachowski, L. & Wachowski, A. (1997). The Matrix screenplay. [Screenplay]. Warner Brothers Entertainment.

[9] Andreoni, J. & Serra-Garcia, M. (2019, December). Time-inconsistent charitable giving. NBER Working Paper No. 22824, https://www.nber.org/papers/w22824 (“the pleasures experienced at the time of the giving decision may be re-experienced later when focus is brought to the giving decision, such as when the gift is transacted. Hence, spreading a single giving decision into two distinct social interactions is like giving a person a larger audience, even if the audience is the same people, and even if the audience is simply themselves (as with self-signaling).”) See also, Andreoni, J., & Serra-Garcia, M. (2021). Time inconsistent charitable giving. Journal of Public Economics, 198, 104391.

[10] Intentionally giving even without any possible impact is actually quite common in experimental studies. See e.g., Crumpler, H., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). An experimental test of warm glow giving. Journal of Public Economics, 92(5), 1011-1021.

Offerings where the gift itself is destroyed are described in the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Pentateuch. See e.g., Genesis [35:14], Exodus [29:41], Leviticus [23:18]; Petropoulou, A. (1987). The sacrifice of eumaeus reconsidered. Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 28(2), 135-149; Strittmatter, E. J. (1925). Prayer in the Iliad and the Odyssey. The Classical Weekly, 18(11), 83-87.

[11] See, e.g., Merchant, A., Ford, J. B., & Sargeant, A. (2010). ‘Don’t forget to say thank you’: The effect of an acknowledgement on donor relationships. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(7-8), 593-611

[12] Xiao, S., & Yue, Q. (2021). The role you play, the life you have: Donor retention in online charitable crowdfunding platform. Decision Support Systems, 140, 113427.

[13] Andreoni, J., & Serra-Garcia, M. (2021). The pledging puzzle: How can revocable promises increase charitable giving? Management Science, 67(10), 4969-6627.

[14] Is it possible for a “thank-you” to be so poor that it doesn’t help? Probably so. One experiment tested this type of “worst case” scenario. In this experiment, the generic “thank-you” calls were not from the charity. They were from an outside telemarketing firm. Also, they were not made until about six months after the gift. Rather than warm, personal, social language, the calls used phrases like,

“This call may be monitored or recorded for quality assurance,” and

“If you have any questions regarding your donation, please call member services”

Although donations were still higher among those who actually received the calls than those who didn’t, the overall effect for being on the list of those who were at risk of potentially being contacted in the experiment was not statistically significant. See, Samek, A. & Longfield, C. (2019, April 13) Do thank-you calls increase charitable giving? Expert forecasts and field experimental evidence. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3371327

[15] “I’m calling to thank you for your gift of [Last Gift Amount] to the Appalachian Fund for our iBackAPP Day efforts! Your participation helped us exceed our 2,500 donor goal for iBackAPP Day and you’re helping make a difference on our campus by providing money for scholarships, student mentoring, faculty research, and other areas of greatest need at Appalachian. As a current student, I want to personally say thank you for making a difference in my collegiate experience!” Dwyer, P. (2020). Gratitude and fundraising: Does putting the ‘you’ in thank you promote giving? [online video]. 2020 Science of Philanthropy Initiative Conference, https://iu.mediaspace.kaltura.com/media/1_oz1cxzxn at [3:46]

[16] Id. at [3:58].

[17] Id. at [4:54]. [Note this difference arose only for actual phone conversations, not for voicemails.]

Related Resources:

- Donor Story: Epic Fundraising eCourse

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- Always Remember – What Matters Most Is the DONOR’s Hero Story, Not Yours

- The 3 Key Elements of a Good Fundraising Story

LIKE THIS BLOG POST? SHARE IT AND/OR LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!