We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

Login

Login

Your Role

Challenges You Face

results

Learn

Resources

Company

How to be an authentic guiding sage for your donors

The guiding sage

The hero’s journey is a universal story. In that universal story, the guiding sage plays a powerful archetypal role.

This role can direct the fundraiser’s work. The fundraiser makes the call to adventure. She challenges the donor to heroism. She helps along each step of the journey. She introduces the hero to friends and allies that help. She provides magical weapons that help. She helps the donor start the hero’s journey. She helps the donor finish the hero’s journey. The fundraiser advances the donor’s hero story.

When the fundraiser fulfills this role, it can be powerful for donors, too. It can satisfy a core need for the donor. It can result in deep, meaningful donor experiences. It can generate transformational gifts. It works.

It works, but it’s hard. Fulfilling this role requires effort. It requires expertise. It requires authentic concern. It demands perseverance throughout the donor’s journey. The guiding-sage role isn’t just a deceptive veneer. To work, it must be real.

Donors are attracted to this helpful, knowledgeable character. But this attraction creates the temptation for phony imitation. Appearing helpful is easy. Actually helping is hard.

The counterfeit mentor

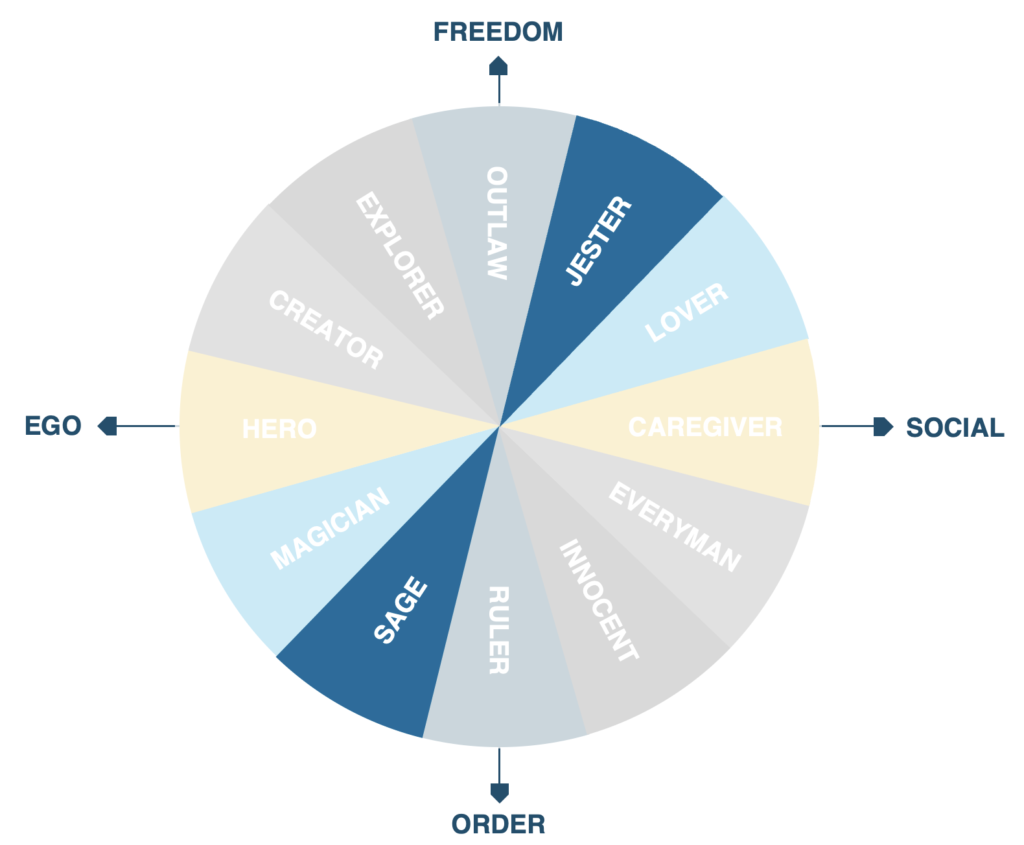

The guiding sage is an archetypal character. But, like other archetypal characters, it has a shadow. This is a similar, but inverted, character.[1] The shadow character for the sage is the jester. The jester is highly social and likes personal freedom.

Like the guiding sage, the jester is also good at talking. But the jester has no substance. The jester provides no real expertise. Like the guiding sage, the jester relates well to others. But for the jester, these relations are short and shallow. The jester quits at the punchline.[2]

These character differences apply to fundraising. Differences in characters parallel differences in practice. These differences include:

- The guiding sage offers expertise. The jester doesn’t know.

- The guiding sage finishes the journey. The jester quits at the punchline.

- The guiding sage focuses on the future. The jester lives for today.

These two characters reflect two competing identities for the fundraiser. They symbolize two competing approaches to fundraising.

1. The guiding sage offers expertise.

The jester doesn’t know.

The guiding sage delivers real value to donors. This means offering expertise for the donor’s journey. The guiding sage should know

- Organizational possibilities

- Gift possibilities, and

- Financial possibilities.

This practical knowledge is useful. But it becomes powerful when combined with relationship. The guiding sage knows the donor. She knows the donor’s values and goals. She knows the donor’s origin story. She understands the donor’s journey. This fusion of practical and personal knowledge works. It creates real value for the donor.

Organizational possibilities

The guiding sage knows what the charity can deliver. She knows how to match this with the donor’s journey. Sometimes, she can push the charity. She can maneuver through bureaucratic barriers. She can help the charity deliver more value to the donor. This might mean

- Tracking and reporting gift impact

- Developing motivational gift structures

- Creating compelling donor experiences

- Delivering donor gratitude, or

- Providing donor recognition and publicity.

These can help advance the donor-hero’s journey. But creating them requires organizational expertise. It requires a knowledgeable insider who acts as the donor’s advocate. It requires a sage. It requires a true mentor.

Gift possibilities

The guiding sage understands gift structures. She knows about

- Endowment gifts

- Virtual endowment gifts

- Memorial gifts honoring a family member

- Gifts in wills

- Gifts-in-kind

- Restricted gifts

- Asset gifts, and

- Other options.

The guiding sage not only knows the options, she also knows how to present them in a clear and compelling way.[3] She knows when donor circumstances make each option relevant.[4] She knows how to match each with the donor’s journey.

Financial possibilities

The guiding sage knows charitable financial planning. She knows how to match options with donor goals and circumstances. In the U.S., this financial knowledge can deliver massive benefit to the donor.

This isn’t just for major and complex gifts. Suppose a donor wants to give only $1,000. For non-itemizers, using qualified charitable IRA distributions or gift “bunching” could save over $500.[5] Making the gift as appreciated assets could save another $371.[6]

Or suppose a donor wants to leave $1,000 in a will. Using an IRA designation instead works better. It could save the donor’s heirs over $500. This works even for the smallest estates.[7]

Financial knowledge creates tangible donor benefit. It means actual dollars for the donors. But many fundraisers don’t know even these basic concepts. Many don’t care to learn. Let me be offensive. If a fundraiser isn’t willing to spend 10-15 minutes a day to learn financial options in charitable planning, then she is not a sage. She is a jester. And she always will be.

The information is free. I personally made sure of that. My charitable planning textbook is free.[8] My 10 to 15-minute animated videos are free.[9] The fundraiser can choose to do the work. She can choose to provide real value. She can choose to help the donor.

But helping the donor isn’t limited to finances. The expert fundraiser can help the donor along the hero’s journey in many ways.

2. The guiding sage finishes the journey.

The jester quits at the punchline.

Delivering the donor-hero’s journey

In the donor’s hero story, the ask is the “call to adventure.” It promises the hope of victory. It promises a hero’s journey. Delivering the hero’s journey is about what happens after the gift.

Was a gift part of a heroic process for the donor? That depends.

- Did the organization confirm the heroism of making the gift?

- Was there recognition of the gift?

- Was there gratitude for the gift?

- Was this expressed by the organization?

- Was it voiced by the beneficiaries?

- Was it confirmed by publicity of the gift?

- Did the organization confirm the heroism of the usage of the gift?

- Was the use reported back to the donor?

- Was it described in a simple, tangible, visual way?

- Did the organization confirm the heroism of the resulting impact of the gift?

- Was there recognition of the impact?

- Was there gratitude for the impact?

- Was this expressed by the organization?

- Was it voiced by the beneficiaries?

- Was it confirmed by publicity of the impact?

These steps advance the donor-hero’s journey. But they are hard work. Both the guiding sage and the jester make the ask. But the counterfeit mentor then abandons the hero. The jester quits at the punchline.

The jester quits at the punchline

This donor abandonment is common. The donor is promised a heroic journey at the ask. Then the donor is abandoned. Later, the donor is promised a heroic journey at the next ask. Then the donor is abandoned again.

The journey itself is rarely delivered. There is no confirmation of the heroism of:

- The making of the gift

- The usage of the gift, or

- The resulting impact of the gift.

What happens? Donors leave. A 2018 U.S. study reported the giving behavior of 11 million donors.[10] About 80% of first-time donors gave nothing to the charity in the following year.[11] If 80% of people who try our product won’t buy it again, we have a problem.

Clearly, the experience wasn’t what donors wanted. What happened at the ask worked. They gave. What happened after the ask didn’t work. They didn’t do it again.

The jester quits at the ask. But the guiding sage finishes the journey. When fundraisers become wise mentors, things change. They don’t just promise to advance the donor’s hero story. They deliver on that promise. They don’t abandon donors in the middle of the story. And, in turn, they are not abandoned by donors at the next call to adventure.

3. The guiding sage focuses on the future.

The jester lives for today.

The effective guiding sage can deliver deeply satisfying experiences for donors. These can lead to transformational gifts for the charity. But this process is not instant. It takes time.

Along the way, there will be temptations to violate the role. These violations might seem like easy ways to grab the cash. But breaking character ends the guiding-sage role. Taking the longer view works better over time. This approach shows up in many examples.

Encouraging gifts of assets

Cash is easy. Assets are complicated. Cash is instant. Assets take time and work. Administrators want cash, not assets. But asset gifts deliver tangible benefit to donors. They’re cheaper for donors.

The guiding sage delivers value. She encourages gifts of assets. This frustrates administrators’ desire for instant gratification. But it serves the charity’s future by serving the donor. Over the long term, delivering value to donors in this way works. Research shows it results in much greater giving to the organization.[12]

Encouraging restricted gifts

Unrestricted gifts are easy. Gift restrictions are complicated. Unrestricted dollars are instant. Restricted dollars take time and work. Administrators want unrestricted cash, not restricted gifts. But gifts with instructions are often more compelling for donors. They are often better at advancing the donor’s hero story.

The guiding sage frustrates administrators’ desire for instant gratification. But she serves the charity’s future by serving the donor. Delivering value to donors in this way works. Research shows it results in greater giving to the organization.[13]

Delivering donor gratitude, impact reporting, and publicity

Taking a gift is easy. Delivering donor gratitude is hard. So is gift impact reporting. So is delivering compatible publicity. But these efforts are critical to the donor’s experience. They advance the donor’s hero story. Delivering value to donors in this way works. Research shows it results in greater giving to the charity.[14] The guiding sage serves the charity’s future by serving the donor.

Advising against interest

Telling donors to do what helps you is easy. Telling donors to do what helps them is hard. Charity administrators won’t understand advising a donor to make a gift:

- Later

- Smaller

- To a different organization

- From a complicated asset

- Through a donor advised fund

- With more restrictions, or

- With income benefits.

But this works. It establishes trust and credibility.[15] It shows that the fundraiser is not just trying to grab fast cash. She is helping. She is a true guiding sage. (This approach of “advising against interest” isn’t just a fundraising technique. It works in all types of sales. This is especially true with stigmatized salespeople.[16])

Over the long term, delivering value to donors in this way works. Research shows it results in much greater giving to the organization.[17] Again, the guiding sage serves the charity’s future by serving the donor.

Planting the seed or eating it

These moments of conflict provide a choice. Pursue instant gratification or invest in the long-term relationship with the donor. Building trust as an authentic guiding sage works. It’s like planting seeds that will bear plentiful fruit in the future. Breaking that character for fast cash is like eating those seeds today.

The guiding sage’s long view secures the organization’s future. It also serves the donor. But it isn’t easy. There will always be the temptation to give up the true guiding-sage role. Reverting to the jester is tempting. The jester is easier. The jester doesn’t need to develop expertise. The jester quits at the punchline. The jester lives for today.

Organizational conflict

Unfortunately, some nonprofits encourage the jester’s “live-for-today” attitude. Some managers don’t understand the long-term benefits of helping donors. Some aren’t staying long enough to care.

Ultimately, this “live-for-today” attitude doesn’t work. It doesn’t work for donors. It doesn’t work for nonprofits. And it doesn’t work for fundraisers. In a national study of fundraisers, “36% of respondents said they left their last job to get away from the old-school fundraising culture of ‘we have to have the money now.’”[18]

The attraction of playing the “live-for-today” jester wears off quickly. It doesn’t offer the depth of a meaningful, enduring, satisfying role.

Conclusion

The authentic guiding sage is a powerful role. It works. But fulfilling this role isn’t easy. Providing real value to the donor is hard work. It requires developing expertise. It requires effort beyond just asking for money. It requires building relationships of trust and value over the long term.

Footnotes:

[1] See previous article in this series: Beyond the donor hero: Fundraising and other archetypal characters.

[2] The guiding sage is known more broadly in myth and fairytale as the “helper” or “Wiseman.” In a similar contrasting parallel, Paul Moxnes of the University of Oslo explains, “The Wiseman is a person with knowledge and competence, a real Doctor of the world, one who can heal, give comfort and good advice. The bad Wiseman, on the other hand, is the False Prophet, the quack, the as-if doctor, the impostor. He is the great pretender, pretending that he has the talent and knowledge of a Wiseman, either by consciously fooling others or also by fooling himself in believing he is competent.” Moxnes, P. (1999). Deep roles: Twelve primordial roles of mind and organization. Human Relations, 52(11), 1427-1444. p. 1434.

[3] James, R. N., III. (2016). Phrasing the charitable bequest inquiry. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(2), 998-1011; James, R. N., III. (2018). Describing complex charitable giving instruments: Experimental tests of technical finance terms and tax benefits. Nonprofit Management & Leadership. 28(4), 437-452.

[4] James, R. N., III. (2015). The family tribute in charitable bequest giving: An experimental test of the effect of reminders on giving intentions. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 26(1), 73-89; James, R. N., III. (2019). Encouraging repeated memorial donations to a scholarship fund: An experimental test of permanence goals and anniversary acknowledgements. Philanthropy and Education. 2(2), 1-28.

[5] Using these strategies the $1,000 can be excluded (via a Qualified Charitable Distribution substituting for the Required Minimum Distribution of an IRA) or deducted (via bunching all gifts into a single year allowing for itemization in that year but using the standard deduction in all other years, often accomplished through a donor advised fund so that distributions to charity remain smooth in all years). Currently, the highest marginal tax rate is 50.3% (37% from federal taxes and 13.3% from California state taxes with state taxes being nondeductible due to SALT deduction caps).

[6] A $1,000 zero-basis asset generates capital gains taxes at a maximum rate of 37.1% (20% federal capital gains tax + 3.8% affordable care act net investment income tax + 13.3% California state capital gains tax with state taxes being nondeductible due to SALT deduction caps). Donating the asset rather than donating cash eliminates payment of these taxes. Donating this $1,000 in appreciated assets (held for more than a year) also generates an income tax deduction of $1,000. For fungible assets such as stocks, the portfolio can remain the same by using the cash not donated to the charity to purchase new, otherwise identical, replacement stock. The portfolio stays the same, but the capital gain is eliminated.

[7] Heirs of any size estate must pay income taxes on inherited qualified plan money, such as a traditional IRA or 401(k). These are forms of IRD (Income in Respect of a Decedent). Heirs pay no income taxes on other (non-IRD) inherited assets. Thus, making charitable donations out of IRD rather than regular assets eliminates these income taxes. Currently, the highest marginal tax rate is 50.3% (37% from federal taxes and 13.3% from California state taxes with state taxes being nondeductible due to SALT deduction caps). Thus, using this technique could potentially save heirs as much as $503 for every $1,000 gift taken from IRD rather than non-IRD assets.

[8] www.encouragegenerosity.com/VPG.pdf

[9] http://bit.ly/TexasTechProfessor or if that link doesn’t work, just search “Russell James Planned Giving” on YouTube

[10] Levis, B., Miller, B., & Williams, C. (2018). 2018 fundraising effectiveness survey report. http://afpfep.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2018/04/2018-Fundraising-Effectiveness-Survey-Report.pdf

[11] The retention rate for first time donors in 2018 was 20.93%. Reported at https://fundraisingreportcard.com/benchmarks/

This loss rate requires massive acquisition of even more new donors just to stay even. On average, for every 100 new or previously lapsed donors who started giving, charities lost 99 previous donors who quit giving altogether. See Levis, B., Miller, B., & Williams, C. (2018). 2018 fundraising effectiveness survey report. http://afpfep.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2018/04/2018-Fundraising-Effectiveness-Survey-Report.pdf

[12] Charities consistently raising gifts from assets experienced five-year fundraising growth rates six times greater than those receiving only cash (using descriptive statistics). For organizations raising over $1,000,000, total average fundraising growth from 2010 to 2015 was 11% (about the same as the combined inflation rate) when gifts came only from cash, but 66% when gifts included gifts of securities. For organizations raising $100,000 to $1,000,000 the average fundraising growth was 7 times larger for organizations raising funds from gifts of securities. (Note that this did not include organizations that received no gifts of securities in 2010, but did in 2015. This included only those organizations that received gifts of securities both in the base year, 2010, and in the end year, 2015. In other words the presence of securities gifts did not arise as a result of the overall growth in fundraising, because the securities gifts occurred both at the beginning and end of the growth period measured.) Beyond this yes/no distinction, as organizations raised a larger share of gifts from cash, total contributions dropped. When they raised a larger share of gifts from securities or real estate, total contributions rose. This was true for every organization size and for every cause type (using all 26 NTEE cause-related categories). James, R. N., III. (2018). Cash is not king for fund‐raising: Gifts of noncash assets predict current and future contributions growth. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 29(2), 159-179.

[13] Chapter 12. Restricted gifts and fundraising story: Conflict and compromise between two worlds. In Book I, The storytelling fundraiser: The brain, behavioral economics, and fundraising story.

See, e.g., Helms, S., Scott, B., & Thornton, J. (2013). New experimental evidence on charitable gift restrictions and donor behaviour. Applied Economics Letters, 20(17), 1521-1526.

[14] Andreoni, J. (2007). Giving gifts to groups: How altruism depends on the number of recipients. Journal of Public Economics, 91(9), 1731-1749; Andreoni, J. & Petrie, R. (2004). Public goods experiments without confidentiality: A glimpse into fund-raising. Journal of Public Economics, 88(7), 1605-1623; Merchant, A., Ford, J. B., & Sargeant, A. (2010). ‘Don’t forget to say thank you’: The effect of an acknowledgement on donor relationships. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(7-8), 593-611.

[15] This can also be true when working with the donor’s advisors. Laura Hansen Dean explains, “Over a long career, gift planners may find that they work with the same professional advisors over and over. Building and maintaining credibility with these advisors is a critical element in the ability of gift planners employed by charitable organizations to close complicated gifts.” Sharing her most memorable donor story, Dean explains, “After [the donor] met with her attorney and investment advisor, she told me that they both had commented about my encouraging her to give herself time to adjust to widowhood before jumping into an irrevocable charitable trust with most of her assets. They were impressed that I had demonstrated that my university was truly committed to the best interest of our donors, not simply to getting the largest gifts we could.” Dean, L. H. (2019). Laura Hansen Dean. In E. Thompson, J. Hays, & C. Slamar (Eds.), Message from the masters: Our best donor stories that made a difference (pp. 65-74). Createspace Independent Publishing. p. 68.

[16] Ashforth, et al. (2007) reference this as “an intriguing variant of confronting client (and perhaps public) perceptions of taint.” They explain, “This involved exploiting those perceptions by acting contrary to them. A manager (no. 1) of used car salespeople provided an example: … I say, ‘Hey take a minute here with me and let me give you Sam’s crash course on car buying … I’ll educate you. I’ll … protect you against those out there who would take advantage of your ignorance.’ And that way …. when they go and meet those types that are still trying to play the manipulation games … people are going to be aware of it and go, ‘Hey, that’s what Sam told us.’ Then my word is going to be validated, and they’ll come back to me and say, ‘Sam, take care of us.’ By acting contrary to the occupational stereotype, the manager hoped to be seen as the exception, thereby gaining the trust of potential clients and possibly even changing their perceptions of the occupation as a whole.” Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., Clark, M. A., & Fugate, M. (2007). Normalizing dirty work: Managerial tactics for countering occupational taint. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 149-174. p. 159.

[17] Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20-38; Waters, R. D. (2009). The importance of understanding donor preference and relationship cultivation strategies. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 21(4), 327-346.

[18] Burk, P. (2013, August 19). Staff turnover: The 3 reasons fundraising professionals leave. [Blog]. https://sumac.com/penelope-burk-on-the-3-reasons-fundraising-professionals-leave/

Related Resources:

- Donor Story: Epic Fundraising eCourse

- The Fundraising Myth & Science Series, by Dr. Russell James

- The 12 Donor Archetypes – How to Tap into Donor Identities and Generate Bigger Gifts

- Why fundraisers who position themselves as a counselor and guiding sage for donors raise more money

LIKE THIS BLOG POST? SHARE IT AND/OR LEAVE YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

Get smarter with the SmartIdeas blog

Subscribe to our blog today and get actionable fundraising ideas delivered straight to your inbox!